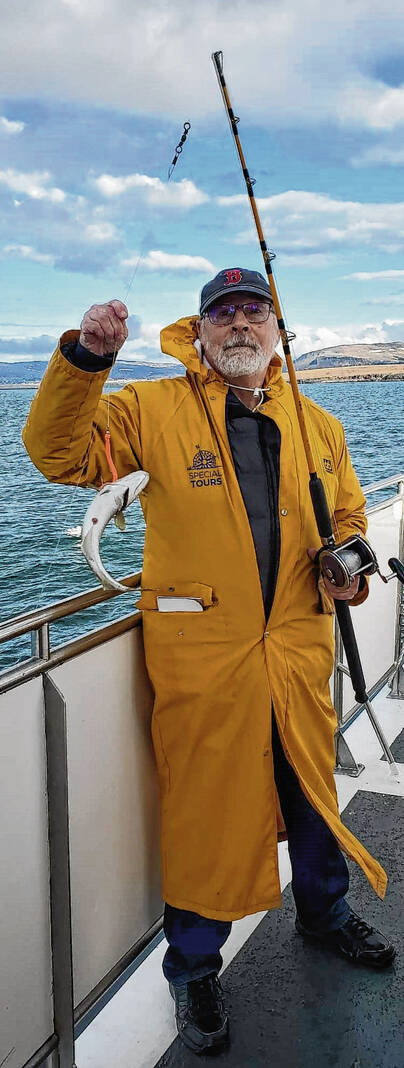

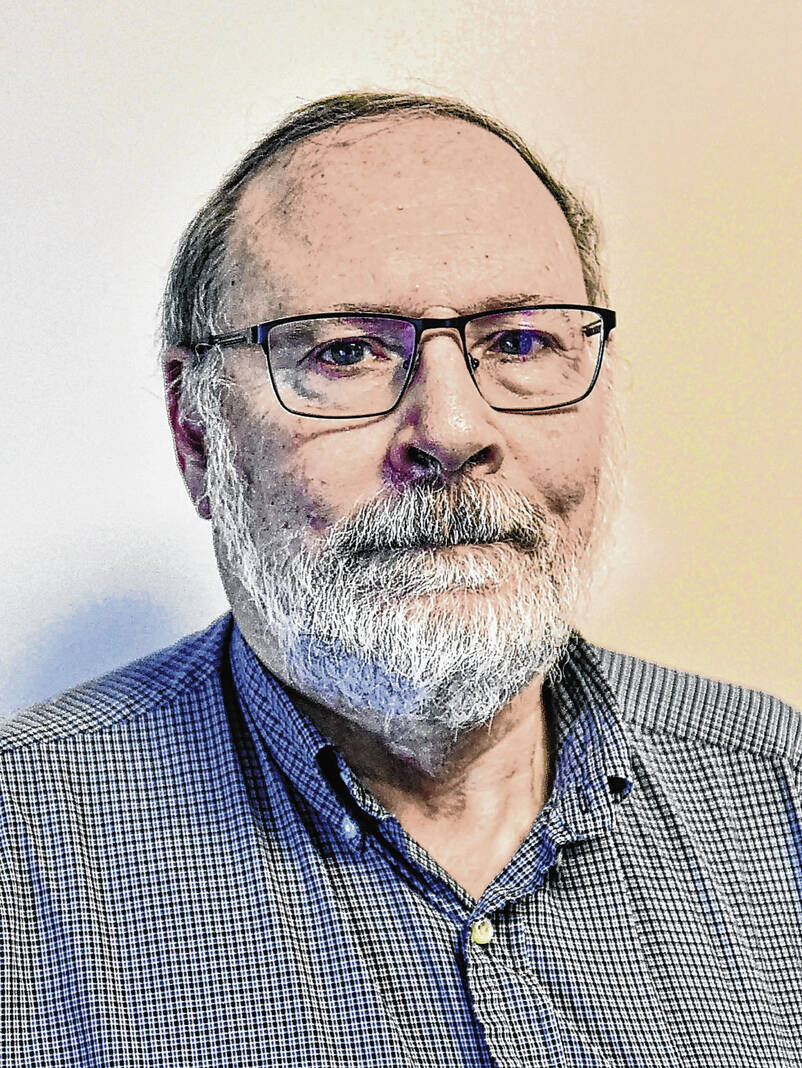

The Tribune’s Lew Freedman catches a fish in Reykjavik’s Old Harbor in Iceland.

Submitted photo

REYKJAVIK, Iceland — The tug on the other end of the line was surprisingly fierce, the hook apparently swallowed deeply by a swimming cod with an appetite.

The lead had carried the line some 65 feet to the bottom of Reykjavik’s Old Harbor off the southern shore of the island and the plastic worm bait’s wiggle had attracted a fish, now fighting me.

Only these cod were likely to be about 14 inches long, not capable of battling with Moby Dick strength in water that was inhabited by humpback whales. I reeled and felt the resistance. I reeled some more and felt the fish give, but with inappropriate power. You never can tell what goes on beneath the sea until the catch breaks the surface.

There was a bright sun and calm water and the boat carried eight intrepid anglers on a late afternoon fishing trip. We were all dressed identically in full-bodied yellow rain gear to keep us dry from splashes. We might have been a sports team, or a collection of commercial fishing pros on “Deadliest Catch.”

The butt end of the rod was firm in my belly, the reel winding with work, when the seemingly world’s toughest little fish came out of the water — with two hooks in his mouth. Sonja, the woman standing to my right, had also hooked the same cod. We had accidentally ganged up on him, thus each earning a half-fish count on our afternoon totals. Only once before had I ever brought up a fish from the deep where I shared the catch.

Well, you don’t see that every day, someone said.

Cod are the staple fish of Iceland, the resource that has kept on giving to the table and the economy for 1,400 years since the arrival of the Vikings. Cod have linked Iceland to the rest of Europe as an export for about 1,000 years. Tourism is a huge element of Iceland’s economy, commercial fishing is the only thing bigger. Thanks to Atlantic cod.

Cod are not as beauty-pageant gorgeous to look upon as rainbow trout, nor are they as weird to gaze upon as other sea creatures such as octopus. In some ways cod are the simple fish of the imagination, fish a foot or so long, with greenish tint and speckled, with three rounded dorsal fins and two anal fins.

In Iceland, if one orders fish and chips at a restaurant, the fish is cod. The meat is white, flakes off easily, and carries a light, not especially strong taste. A cook can grill it, bake it, broil it or fry it. In more modern days, Iceland has had to fend off interlopers from NATO countries arriving from international waters fishing for their own cod. There were three distinct Cod Wars, starting in 1958, and United Nations Law of the Sea conferences, all designed to protect Iceland’s historical fishing grounds. Now, the cod harvest is regulated, limiting the number of tons taken from the ocean so as to preserve the species. Our sport angling group’s impact was negligible.

The average outdoorsman visiting Iceland is not seeking an education in international politics, but merely a chance to wet a line. There were seven of us aboard a sturdy fishing boat for a 5 p.m. departure from the harbor. We were charged $110 for the guided, three-hour trip, fortunate to have good weather day with no chop in the water and mild, 40-degree temperatures on deck in early May.

Crew members for Special Tours Reykjavik ranged from a veteran captain who did not speak English, to an assistant guide whose specialty was whale watching and downplayed his fishing talents. Lucas said he would be the worst angler on board. I responded that it would probably be me. I bet Lucas an Icelandic penny I would catch fewer fish than he.

Some were beginning anglers from England who had never fished before. Sonja and Caitlyn, next to me, were from the Toronto area. Sonja had visited 80 countries and fished in 20. I asked about her greatest catch. She cited a piranha caught in the Amazon.

Piranha mention provokes a reaction given their fearsome killer reputation and sharp teeth. She held her hands about a foot apart, designating the size, but made it clear length was irrelevant. Sonya smiled, baring her own teeth, and said, “But I caught a piranha.” Caitlin hauled in a grand-daddy of our cods, with about three times the girth of the average ones. I caught six cod, or five-and-a-half, as it may be, and that was a common harvest. We kept larger ones and liberated smaller ones.

Lucas was at the stern, far from me up front, so did not witness my disaster. After I caught a keeper, I handed my camera to Caitlyn, who snapped a picture, then handed it back. Only somehow, with all my layers, yellows, light parka and sweatshirt, I did not properly replace the camera around my neck.

The camera hit the deck, but then it slipped under a four-inch gap in the deck wall and soared overboard. I was stunned. For a moment, the camera floated in sight. I yelled for a crew member to hook it, but the camera slipped beneath a wave before he could perform a rescue. There went my favorite camera of all time containing the digital chip with photos of my first four days in Iceland.

Lucas, unaware of my gaffe, and of the inability of the crew to gaff the camera, heard the tale. “So it floated there like the Titanic,” he said, rubbing it in. Lucas said he caught no fish, but I gave him an Icelandic penny, anyway. We had not realized the coin was decorated, appropriately enough, with a cod. He joked my payoff was rubbing it in.

As we headed to port, crew members cleaned the largest of the cod and cooked them up to eat.

Photographs are supposed to preserve memories. The angst of losing the camera aside, I am sure the cod fishing experience in Iceland will remain vivid forever.