Longtime Park Ranger Cookie Ferguson leads a birding excursion at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

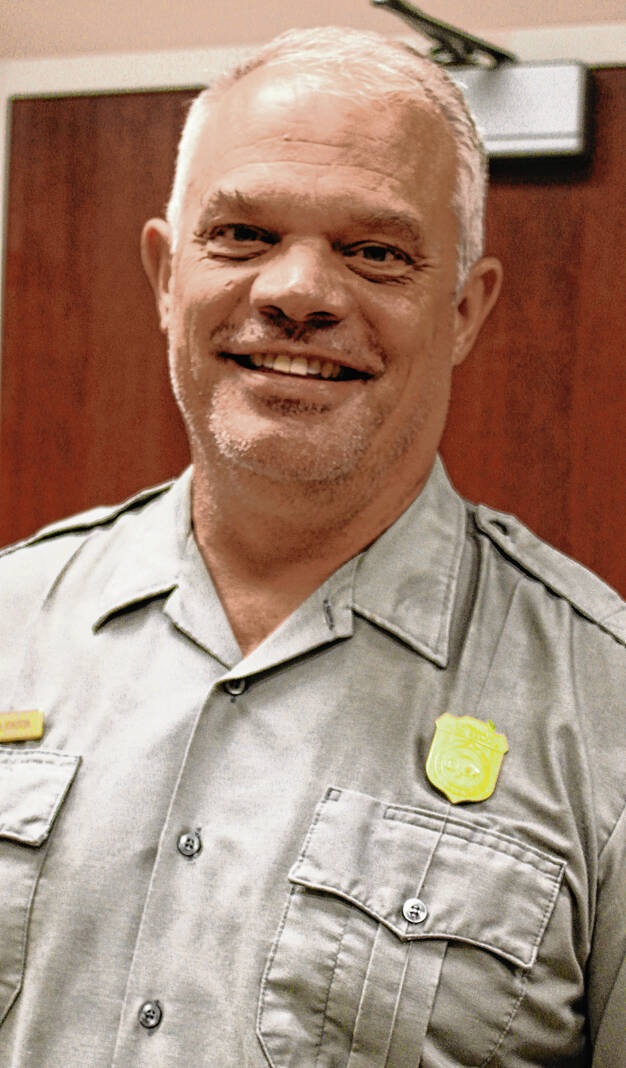

Bruce Rowe has been an educational ranger and public information officer at Indiana Dunes National Park for more than 30 years.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A hawk pauses from flight in a tree at Indiana Dunes National Park during a morning birding excursion.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A dune at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Ranger Rafi Wilkinson supervised the recent Indiana Dunes National Park Outdoor Adventure Festival of more than 100 events.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Footprints on a sandy trail at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Lake Michigan lapping the shore at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

This generating smokestack in Michigan City mars the view by Lake Michigan from parts of Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

These chickens live at the Indiana Dunes National Park Chellberg Farm, founded in 1885.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Two people walk along the beach at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A replica glider hanging from the ceiling in the visitors center in honor of aviation pioneer Octave Canute who used Indiana Dunes National Park for experiences in flight.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Indiana Dunes National Park sign at the visitors center in Porter.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Couples can some days take somewhat secluded beach walks along the shore of Lake Michigan at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Showing off a self-made T-shirt indicating Indiana Dunes National Park was this man’s 59th out of 63 national parks he has visited.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

The Chellberg Farm dates to 1885 at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Oliver Nicholson, 10, imitates a bird on a sand dune overlooking Lake Michigan.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

This sign welcomes birders to the central beach area at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Goats are some of the animals living at the Chellberg Farm at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A wood duck tries to blend with the landscape in a marshy green area at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A group of about 15 birders, most beginners from about a half-dozen states, turned out for a morning trip to spot birds at Indiana Dunes National Park.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

This spectacular Lake Michigan shore pink house originated at the 1933-34 Century of Progress World’s Fair.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

PORTER — Tom and Victoria’s T-shirt wardrobe advertising their quest was a showstopper.

It was not because the duds were fancy but because the black lettering on white summarized a story.

It explained what the senior citizen Florida couple was doing in northern Indiana. The message read: “Visiting all 63 national parks in the United States.” Printed just in front of the 63 was a 59 crossed off. Indiana Dunes National Park was the twosome’s latest check mark on a life list.

For decades, the beaches adjacent to Lake Michigan were acclaimed as a special place and carried the designation of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. That changed, however, in 2019. More than 100 years after people began trying to categorize the dunes as a park, that became reality, altering everything in the public eye.

“The name change, it was amazing,” said Bruce Rowe, a ranger who has worked at the dunes for more than 30 years. The switch from lakeshore to park was almost like magic. “That day, we began getting calls from around the country.”

That day was Feb. 15, 2019. Indiana Dunes National Park is Indiana’s only national park among the 425 so-called “units” around the nation that include monuments, preserves, battlefields, lakeshores, supervised by the National Park Service.

George Rogers Clark National Historic Park in Vincennes and Abraham Lincoln’s boyhood home in Lincoln City are Indiana’s two other units. But Indiana Dunes National Park with its 15,000 acres sprawling across communities such as Gary, Porter, Portage and Michigan City is the only national park.

Ranger Ryan Koepke, in charge of fee management, has earned some national notoriety. Framed on the wall of Koepke’s office is a newspaper story noting how two and a half months after he asked the U.S. secretary of the interior in 2019 why there was not free park admission for military veterans, it became a rule.

Koepke said the park’s changeover was dramatic.

“We went from the freshman team to the varsity,” Koepke said.

According to Rowe, in 2018, the last year before the switchover to national park status, the Indiana Dunes catalogued 1,756,000 visitors. In 2021, post name change and COVID-19 pandemic, there were 3,177,000 visitors.

Unlike many national parks in the West, in Alaska or in American Samoa, Indiana Dunes National Park is as highway accessible as a Subway or McDonald’s, right off Interstate 94. Porter, location of the visitors center, is 46 miles from Chicago and 160 from Indianapolis.

Rafi Wilkinson, a 10-year park ranger, once figured out there are 30 million people within three hours of the park.

“It’s still amazing to me there are way too many people who don’t know we’re here,” he said.

Wilkinson has worked to remedy that. Over 10 days in September, he oversaw the Indiana Dunes Outdoor Adventure Festival featuring 100-plus events with spillover to other local parks.

Included were hikes, talks on ecology, photography, history and more, birding trips, facility tours, a sunset horseback ride, kids’ scavenger hunts and paddling.

The dunes is generally ambitious planning visitor-friendly activities, waging a full-scale war against boredom. There is a program every day between Memorial Day and Labor Day and every weekend of the year “even in the dead of winter,” Rowe said.

The T-shirt couple were not the only people crossing the Indiana Dunes off a park life list. In casual meetups, a California couple revealed this was their 44th park, and a Pennsylvania couple said it was their 25th.

Colin Thomas, 43, of nearby Homewood, Illinois, was on a day trip with 4-year-old daughter Elloren. He has visited 115 of the 425 park units and plans to ensure his little girl sees them all. She has already been to 60.

“Anything within five hours, we’ve done,” Thomas said.

When he was a kid, he said, his family regularly visited the dunes.

“It’s so nice and close,” he said. “I love anything with water.”

Fishing

Water is a key feature at the park with the sprawling Lake Michigan drawing the eye, but besides boat tours, there are fishing possibilities in the lake and in tributaries.

Steelhead runs are prominent part of the year and Chinook, or king salmon, can be captured at the right time, including an early fall run.

Koepke is a passionate enough angler to have a fishing lure tattooed on his right arm, said surprisingly, sometimes night fishing is best.

He said anglers can fish with guides on the big lake in big boats out of various nearby cities. But not to be overlooked are piers in and around the dunes, which has some designated fishing days and programs. The excitement for many is “they can catch a 20-pound steelhead,” he said.

Trails to follow

Mount Baldy is the best-known sand dune. The trail of sand 126 feet high near Michigan City is just 0.3 miles long with much of it uphill, twisting through trees leading to breaking waves. The tallest mountains in the United States may be in national parks, such as Denali, at 20,310 feet in Alaska, but these dunes are mere bumps in the landscape.

The lake water may be sparkling blue, and couples take romantic walks on the beach, but the view from the high point is somewhat incongruous for a national park. Old industrial buildings can be seen and one pulsing smokestack in downtown Michigan City.

The Michigan City Generating Station is a hurdle to get past in the scenic landscape. Built on the site of a former sand dune, the functioning station is a coal and natural gas plant anomaly expected to run down, probably by 2028 and be demolished.

There are numerous other access points from State Road 12 to the Lake Michigan shore. In all, the park has 50 miles of trails with 15 miles of shoreland.

“There are tons of nooks and crannies,” Wilkinson said of the ins and outs of the park’s roads.

Many visit the 1885 Chellberg Farm and Bailly Homestead.

Joseph Bailly built a home in the 1820s, and family members lived there for a century. Park employees still grow vegetables at the Chellberg Farm, and cows, goats, chickens and turkeys live on the premises.

Elloren Thomas, Colin’s daughter, was taken by the animals.

“The chickens are my favorites,” Elloren said.

The vegetables raised, said ranger Brittany Mathes, get transferred to a produce stand by the side of the road and are sold by the supporting Friends of Indiana Dunes.

History

New park, but old history.

Only students of certain aviation disciplines, or patrons of the Indiana Dunes, are likely to know about Octave Chanute, who long ago made practical use of the sand.

He developed principles of flight at the dunes and corresponded with Wilbur Wright, who along with his brother, Orville, is credited with inventing the first airplane.

Chanute, born in France in 1832, later moved to the United States and made a career in the railroad industry. But he became fascinated by flight upon seeing a hot air balloon ascend in Peoria, Illinois, in 1856.

Subsequently, Chanute used Miller Beach at the dunes as a laboratory testing hang gliders and aviation ideas incorporated into a revolutionary 1894 book called “Progress in Flying Machines.” Chanute eagerly shared his thinking with the Wrights, visited them in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, and exchanged letters. When Chanute died in 1910, he was described as the father of aviation.

That is why if millions of park tourists look up to the visitors center’s ceiling, they see a hang glider suspended overhead.

Efforts to preserve the dunes, not as a landing strip but for its vast biodiversity, began in 1899. The park claims 350 bird species and more than 1,100 types of flowers and grasses despite being a disconnected stretch of territory with cities, housing developments, former steel mills and smokestacks interspersed.

Not much in the way of the sexiest North American mammals, no bears or elk, but sightings of coyotes, red fox, bobcat and otters.

The curb appeal stems from the sands and Lake Michigan, one of the five Great Lakes, 22,404 square miles in size, though commingled among those communities is a startling amount of nature.

“The density of our biodiversity is unbelievable,” Wilkinson said.

The first move to preserve the dunes as a national park took place in the early 20th century. One supporter was Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, created in 1916.

Mather wanted to make the dunes a national park and presided over hearings to measure public thinking. While more than 400 people came out and 42 spoke in favor without opposition, the idea withered.

The combination of industry clout seeking to construct a Port of Indiana, steel mill operators flexing muscle, and the United States entering World War I deflected plans. Instead, in 1926, a 2,182-acre Indiana Dunes State Park opened. In a rather confusing situation, it remains a separate entity in Chesterton within the national park boundaries.

Much lobbying to protect the lakeshore was led by women who sometimes later were called “Wonder Women of the Dunes.” Sands of time may have passed at the dunes, but they did not disappear. In stages, this early sentiment led to the creation of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in 1966, and finally, in 2019, the classification as a national park.

Wilkinson thinks of the determination to change the dunes’ status in 2019 as an attitude of “Let’s finish the job.”

Given the patchwork of industry wrapped around the marshland, wetlands and bogs, the water and sand, the 25-mile-long national park, stretching from Gary to Michigan City, has limited room to grow.

The largest national park is Wrangell-St. Elias in Alaska at 8.3 million acres. Indiana Dunes is 58th in size with its 15,067 acres. Even this comparative sliver of land was not easy to piece together.

“That was the result of 7,000 real estate transactions,” Wilkinson said. “We are a quilt you can’t believe.”

Birding

Some 15 birders gathered at the visitors center for a morning tour at Central Beach with ranger Cookie Ferguson on a stunningly blue sky day with temperatures in the 60s. There were people from Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, Maryland, Georgia and Illinois, though presumably the birds were local since the migratory season had not yet begun.

Most participants were retirees, but homeschooled Emily Nicholson, 13, and brother Oliver, 10, had this as a learning day under the guidance of their guardian. They have bird feeders in their backyard, and Oliver was prepared with his own binoculars, although the park lends them out.

“Habitat, habitat, habitat,” Ferguson said of what attracts birds to a spot.

A large variety allowed themselves to be seen or chirped loud enough to be heard, including a blue jay, woodpecker, wood ducks, egrets, a hawk and more. Other birds were coyer, around but not really visible.

“The birds take classes on how to hide from birders,” Ferguson said. “They hide in the leaves.”

The houses

The Century of Progress Chicago World’s Fair of 1933 and 1934 teased visitors with examples of Homes of Tomorrow. After the fair, a bold real estate developer named Robert Bartlett transported five of the structures to Lake Michigan’s south shore, where they remain inside Indiana Dunes National Park with National Historic Places designation.

Four were moved by barge and one by truck, and they are rented. Otherwise, the public is allowed to tour the beachfront homes just once a year in September.

The houses perch along a strip of road near other million-dollar homes and remain showpiece curiosities gawked at by drivers. The flat-roofed Florida Tropical House is an all-pink building with exterior painted over stucco. Construction materials included travertine, limestone, concrete and clay, and the marvel of a backyard is essentially Lake Michigan.

Ironically, 90 years after being built, the Florida Tropical House has gained some new unofficial notoriety as “The Barbie” house. This is due to the popularity of the 2023 movie in which Barbie the doll, also pretty in pink, comes to life.

It is possible Barbie now may stop by to check Indiana Dunes National Park off her life list, too.