Indiana Conservation Officer Tony Mann speaks to the crowd as he roams the room emphasizing key points to learn before the hunter certification test.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Melissa Cushman shows the crowd the proper way to handle a pistol.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

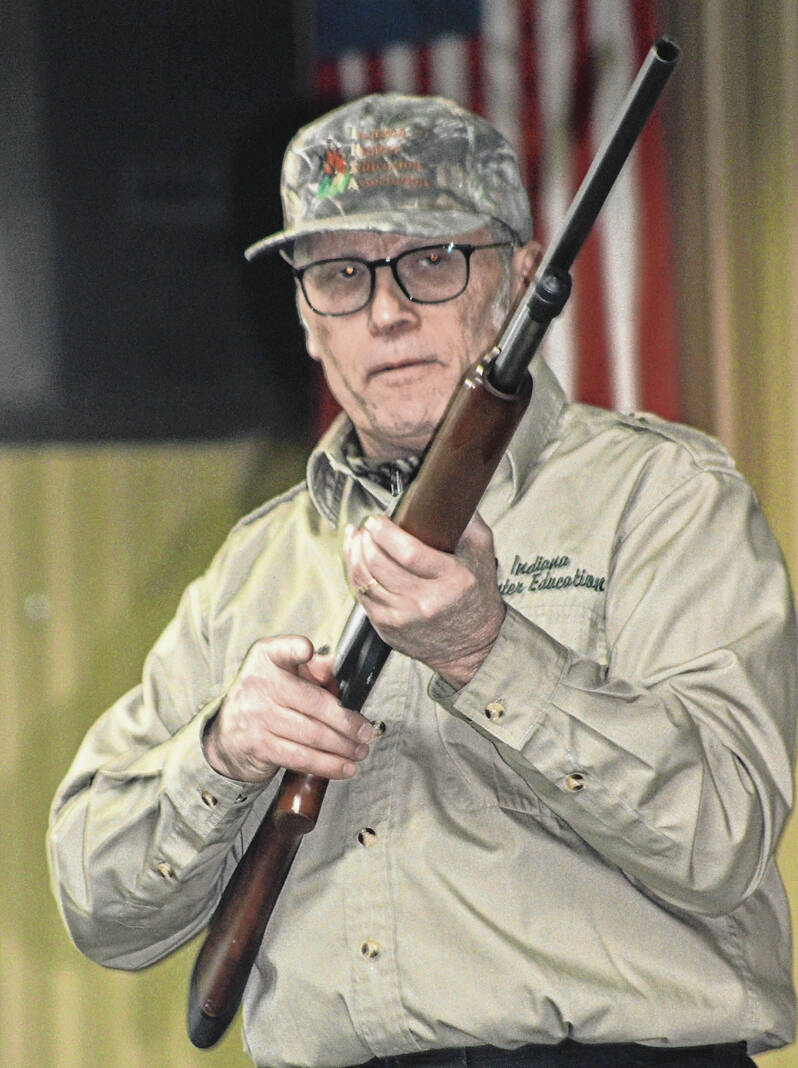

Hunter education instructor John Rickelman helped demonstrate safe use of shotguns.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Indiana Conservation officers Jonathan Watkins, left, and Tony Mann supervised the two-day hunter education program at the Dubois County Fairgrounds.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Indiana Department of Natural Resources Conservation Officer Jonathan Watkins speaks to a crowd of about 130 students at a recent hunter education program at the Dubois County Fairgrounds.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Hunter education instructor Dana Reckelhoff shows off an arrow beginning hunters may use when they go into the field.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Indiana Conservation Officer Tim Kaiser, a canine patrol specialist, made a cameo appearance with his 9-month-old, still-in-training chocolate Lab, Ember.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Instructor Tim Lueken emphasizes safe handling of rifles when beginners go into the field for the first time.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Ed Boeglin helped lead an archery presentation with the assistance of a deer decoy.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

HUNTINGBURG — Indiana Conservation Officer Tony Mann has a loud voice and uses it as a weapon the way a teacher shushes chatterbox kids to cajole attention.

Right off, at the beginning of what would be 11 hours of intensive lecturing, the 30-year Indiana Department of Natural Resources officer delivered strong messages with the timber of a megaphone.

It was a no-messing-around voice, and the words were no-nonsense, too, for the approximately 130 attendees at a recent Indiana Department of Natural Resources hunter education course that culminated with a 100-question test.

“Don’t be texting your girlfriends,” Mann said. “No, it’s not an open book test. And no cheating.”

The late January class in the Dubois County Fairgrounds Clover pavilion is designed for learning and certifying for young hunters, especially with limited field experience, to hopefully provide lessons for a lifetime.

One key communique is that paying attention in the here and now can affect decisions made in the woods and the wild resulting in life and death. Not merely for an animal being hunted but for a friend or family member hunting with a hunter. No fooling around with loaded weapons.

“My goal tonight,” said Jonathan Watkins, another conservation officer supervising the classes, “is to make everyone a safe, responsible sportsman.”

Some 150 signed up for this class, the biggest in Indiana, though there were some no-shows. Before hunters are licensed to pursue deer, turkeys and the like across Hoosier lands, they are to become state certified.

DNR Lt. Andy Hagerty said the state runs between 250 and 300 hunter education classes per year. Anyone born after Dec. 31, 1986, is required to take the course now, and in an average year, between 6,500 and 7,000 people do so in person and another 6,500 to 7,200 take it online.

The goal, Hagerty said, is to “provide educated, involved and safe sportsmen.”

Theoretically, facts can prevent accidents and lead more hunters to follow game regulations.

‘Scared straight’

The vivid short documentary using actors could well have come with a “parental guidance advised” note. It made the no sugarcoating it point that flouting rules and safety practices can result in you shooting to death your friend in the field in a bloody mess and then going to jail for life as a criminal.

After the hit-them-in-the-face video was shown to a crowd that included 100 students 17 and under, Mann asked if everyone was OK.

Bad things can happen when guns are loaded in untimely ways, are carried in a sloppy manner or are pointed carelessly near other people. The message emphasized was how a few seconds ruin lives because of “a stupid mistake,” Mann said. He cited real-life examples of gun deaths nearby in Indiana.

“That kind of stuff does happen,” he said. “I don’t want that to happen to you. I hope I don’t have to see you dead.”

Both the film and Mann’s follow-up comments were dramatic, and the audience was rapt. There was no texting. There was no whispering. Those riveted to their seats, many accompanied by parents or grandparents, kept eyes straight and responded with increasing frequency when posed questions.

The powerful common theme of the film and speakers shrieked “safety.” Safety spelled out, shouted out, illustrated, explained in detail. Instructors did everything but hand out xeroxed copies from the thesaurus synonym page on the word safety.

Making the right choices and acting safely should be adhered to even in the face of peer pressure, Mann said. Peer pressure could take the form of taunts implying someone was a poor hunter because he hadn’t taken his deer yet or being browbeaten into trespassing on private land.

As another visual aid — a take-home one — students received copies of Today’s Hunter, a DNR magazine labeled “Indiana’s guide to hunting responsibly and safely.” Officers asked readers to flip to Page 50. The headline stated “Be A Safe Hunter.”

Safety details followed over several pages, including the best ways to carry a shotgun or rifle while hiking through the woods to being hyper-aware of surroundings. It is all important to point the muzzle away from people, at the ground, perhaps the sky, depending. It may surprise some just how far a bullet can travel.

“Shooting on video games is not the same as real life,” Mann said.

In the present-day climate, the intense emphasis on safety and the harm that can be done by ignorance in transporting, handling and shooting guns during a hunter education program is no accident. Virtually simultaneous to this program, or immediately after, in California and Louisiana, there were mass shootings killing and wounding a multitude of people. While those incidents involve extremists, hunters can sometimes be caught in the crosshairs of blowback.

Taking behavior one step further, Watkins dove into hunting ethics. Since the late 1800s, as Americans mostly shifted from subsistence hunting into “sportsman” hunting, the fair chase ethic has been a critical model.

Fair chase applies to hunting of big game roaming wild and free, and the idea was attributed to President Theodore Roosevelt and the Boone and Crockett Club, which he helped found in 1887.

Watkins succinctly explained ethical hunting, largely to an age group still forming its own moral code, but in terms easily understood. This would especially be so if they are still under the roofs of parents setting the rules of the household.

“Ethics is knowing the right thing to do and doing it,” Watkins said, “even when no one is watching.”

Watkins compared solo hunting situations with crossing a Walmart parking lot and stepping on a lost $100 bill. Should you keep it, no one the wiser, or turn it into the store manager?

Uninformed or reckless behavior in the wild, shooting at the wrong time, in the wrong place, Watkins said, might mean, “You are committing a crime against wildlife. There are no referees to blow the whistle on you.”

Throwing a little fear, however, into the beginners, Watkins backtracked a trifle.

“There is a referee in this game,” he said, meaning conservation officers like him enforcing laws. “The hammer is going to come down and you go straight to jail.”

Watkins showed another film that could be described as a compilation of jerk behavior with hunters taking more game than the limit prescribes, showboating with harvested animals, littering, shooting from vehicles, shooting across a road with a jogger nearby or drinking alcohol while hunting.

Responsible hunters abhor this behavior, and fast-learning students in the room readily shouted out violations spotted, veritable tipsters for enforcement.

Given the desire to shoot that first deer and prove hunter expertise, Watkins said it is important for adults to tamp down any itching, blinding youth urgency for animal killing.

“We have to teach our children it’s not about harvesting something,” he said. “That’s hard.”

One of the most important lessons, Watkins said, is hunter appreciation of the environment, being out in the wilderness, in the cold, yes, in the clear air of dawn.

“That’s when the magic happens,” Watkins said. “That magical event when the sun comes up. The woods come to life. We are out there to be in nature, to be one with nature.”

Safety first always

Bow and arrow use. Shooting shotguns. Firing pistols. Loading muzzleloaders. Aiming rifles.

How to, when to, where to and most emphatically how to handle these hunting tools safely were explained along with description of how a hunter is a conservationist by contributing to game management and survival in the woods.

“We’re using it wisely,” instructor Scott Fromme said of hunting to prevent too many animals competing for food in the same habitat.

Even though no apples were shot off heads of volunteers, William-Tell-like, Dana Reckelhoff and Ed Boeglin talked bows and arrows and showed off a deer decoy prop, pointing out the best angles for good shots. They offered lessons, tips and wry observations.

“The problem is do they ever run toward your truck?” Boeglin said of a wounded deer. “Nah. They always run the other way.”

Tim Lueken, Eli Mundy and John Butler discussed rifles. Butler said loading in the vehicle on the way to the happy hunting grounds is a no-no.

“That’s a trip to the ER,” Butler said of an accidental discharge due to a bump in the road leading to a hospital visit.

Advising adults, Lueken said it is a mistake to be protective mixing ammo for their gun and an accompanying youth’s.

“If your son or daughter is old enough to carry the gun, they’re old enough to carry the ammunition,” Lueken said.

Muzzleloader Zach Mauder offered what may have been little-known knowledge in saying, “If black powder gets wet, it doesn’t ruin it.” Black powder apparently holds up better than cheese in the fridge, as well.

“Black powder doesn’t weaken with age,” he said.

Regardless of utensil, the repetition of safety lessons worked its way through the presentation. Pistol instructor Hannah Beck said people must handle handguns “like your life depends on it because it does.”

Andy Lueken, shotgun specialist, said “a safety is a mechanical device that can and will fail.” He parroted what was said in nearly identical fashion by each group. Students were told the best safety device is their brain.

Mann and Watkins warned early if students heard something twice, three times, it was important and almost certainly be on the test.

Any new hunter sitting through hours of presentations who took home a magazine and a hunter education Today’s Wildlife booklet could never say he was ignorant of the rules of engagement.

With hunting license sales declining across the country, Mann and Watkins were heartened to see the 100 energetic youth participants.

Mann, 56, said the region is a stronghold of hunting and “to see the amount of kids, it’s awesome.”

Watkins, 40, an officer for 17 years, called the youth turnout “very encouraging. This is the future coming at us.”

A future of, if not straight shooters, at least safe ones.