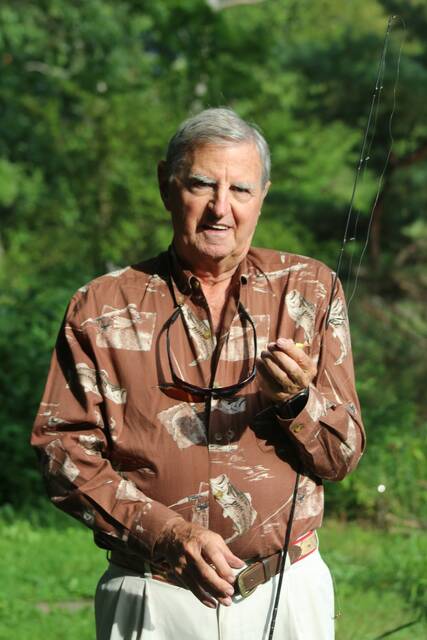

Dan Basore holds a simple, modern lure for fishing in his backyard pond.

Lew Freedman

An antique fishing lure.

Lew Freedman

Dan Basore holds a mount of a 25-pound Brazilian peacock bass that usually hangs on the wall in his living room.

Lew Freedman

Once, Dan Basore decided to have a sale of some of his old gear and was stampeded by buyers.

Lew Freedman

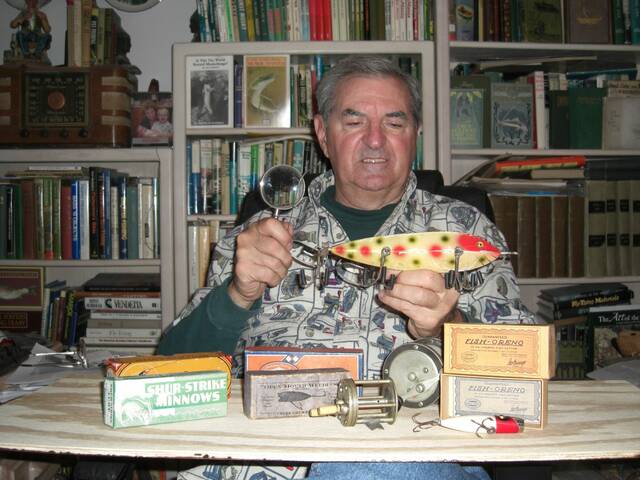

Fishing lure collector Dan Basore holds a very rare Heddon musky lure, one of only six made.

Lew Freedman

Part of a large display of antique fishing lures that Dan Basore sometimes shows at Midwest outdoors shows in Indianapolis, Chicago and Milwaukee.

Lew Freedman

A mixed variety of fishing lures made by different manufacturers across the decades.

Lew Freedman

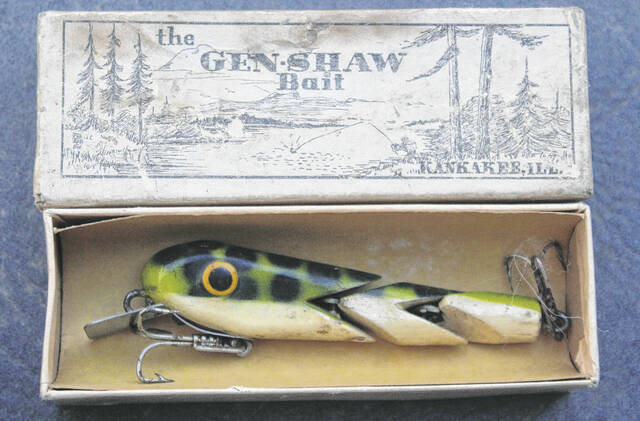

A classic old-style fishing lure, complete with the box it came in.

Lew Freedman

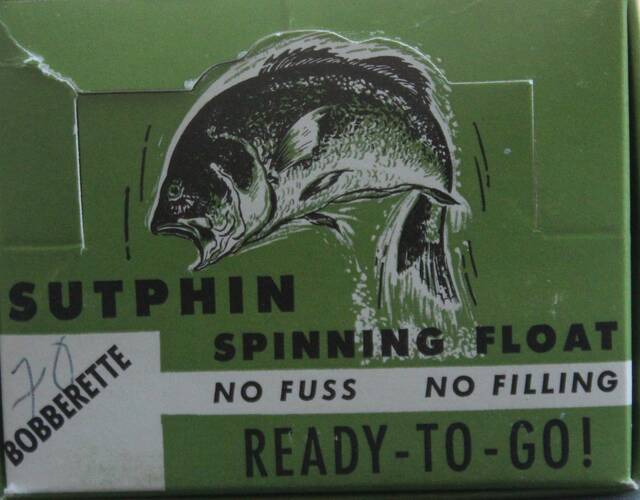

As a youth, Dan Basore grew up nearby the Sutphin Bait Shop, which was also the home of a brand of fishing lures.

Lew Freedman

The remark was made in off-handed fashion to the King of Lures. Some 10,000 fishing lures must have passed through your hands over the decades, right?

“More,” Dan Basore casually replied.

Old ones, new ones, rare ones, big ones, small ones, lures for fish of all types, lures to fool fish of all sizes, the King of Lures has seen it all, seen them all, and if not owned them all, is aware of the origin, heritage, manufacture and story behind just about every fishing lure known to mankind.

Basore, 79, originally from Indianapolis, where he discovered fishing, is walking encyclopedia of lures.

Ten thousand? one friend of his scoffed.

“Oh yeah, probably nowhere near that,” said Keith Bell, who operates a company called mybaitshop.com near Green Bay, Wisconsin and sells an estimated 50,000 lures a year. “Probably 10 times that.”

So for Basore, it is more like 100,000 lures coming and going, bought, sold, traded, studied, analyzed, displayed over a lifetime passion. An ardor that began in Indiana, was rooted in Indiana for four decades, before transplanting to the Chicago area almost four decades ago.

And yes, he has actually fished with them — not all of them, of course, but many — in Indiana and Illinois, naturally, but in rivers, lakes and oceans in another collection of states and nations. One prized catch is memorialized in a mount on his living room wall — a 25-pound Brazilian peacock bass. And Basore has also landed a 400-pound marlin.

There is no definitive ranking system taking note of the world’s biggest, most knowledgeable, expert, devoted collector of fishing lures, but Basore is a luminary in the field and on the short list.

For anyone seeking to put a number on the fishing lures Basore has saved, used, or even parted with, he provides a consistent, wry, if straight-forward answer.

“If you can count them, you don’t have enough,” he said.

Given how meticulous his paperwork is, how careful he is to document his fishing life and lure collecting, Basore may truly really know the number. But since he first began collecting and trading at 15, maybe not.

After all, on one occasion alone, Basore acquired 3,347 lures.

Lures as art

Basore has a lovingly-cared-for pond in his back yard in Warrenville, Illinois stocked with bluegill, largemouth and smallmouth bass and a variety of other fish.

It is a bucolic setting, surrounded by trees, the water a few steps out the door of his home, where he can fish in the shade every day — and does.

Basore’s intrigue with fishing began young, when his mother, Emma Basore, who died in 2020 at 99, started reading him stories at age 2.

When she discerned his interest, she scrounged up a fishing pole and he tried the sport. Who could have imagined what it would lead to?

Basore was the oldest of four children, three boys, and was not close to his father Robert. His mother was the influence.

“She was, and is, my guiding light,” Basore said of his mother.

The family lived close to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and also near a bait shop operated by Charlie Sutphin. Sutphin gave him a job later, Basore bought the older man’s collection when he was going out of business.

Basore was born in 1942 and when he was a youth, few cared about fishing lures as collectibles. Even many old ones could be obtained for 25 cents.

Basore became a proficient fisherman and did well in tournaments at the Marion County Fish &Game Club. Ultimately, a sunfish won a kids event and capturing his first trophy sparked a stronger affection for angling. In 1971, he also won a major casting tournament and $2,750, a good payday for the time.

“Oh, I tell you, I love it,” Basore said of fishing. “How could anyone not love it?”

He was 15 when a grandfather passed away, leaving him a tackle box. Some of them were 30 or 40 years old.

Silver-haired and ruddy-faced, Basore is retired, but over the years he has been a golf caddy, a drag racer (he can still hear the engines revving in his head from his Indy days) a tournament fisherman, and a financial advisor. He spent 35 years writing about fishing and lures for Midwest Outdoors and just about anyone who has attended a major outdoors show in Indianapolis, Milwaukee, or in the Chicago area should recognize him and his lures.

No doubt Basore was an accomplished caster and angler, but what got him inducted into the National Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame in Hayward, Wisconsin was his devotion to fishing history.

For years, Basore has put together display cases and tables at those outdoor events attended by thousands. Sometimes displays feature antique lures, sometimes those made by specific manufacturers. His lures have been part of displays at Bass Pro Shops stores — he was friends with founder Johnny Morris since before the stores existed.

Once he had a job and career, Basore had more money to fish in far-off places such as Alaska, Argentina, Brazil and Costa Rica. But in some ways the lure of the lures trumped the lure of the fish.

“I will never catch a fish that no one else has ever seen,” he said.

Yet he did uncover mysteries about the the makers of some lures, was able to trace their history, and in some cases got to know the creators. When they died, he already knew family members no longer wishing to hang on to the deceased’s collection in the garage. Basore anted up a fair price and gathered thousands upon thousands of lures and fishing memorabilia items.

Over time, as the hobby matured, so did the lure value and he sold duplicate rarities to fund his own collection.

Basore accumulated lures, hooks, rods, catalogues from defunct companies, photographs, letters and paperwork. Materials fill garage and basement space.

Not all is precious to Basore. Not all is valuable as individually. What may have cost 25 cents once upon a time may be worth $10, or $100 now. That’s a huge markup, but doe not represent a fortune.

By comparison, baseball card collecting can be much more lucrative. A few weeks ago, a 1909 Honus Wagner baseball card sold at auction for $6.6 million, the highest price ever paid for a sports card.

The most money ever paid for a lure is $101,200, one called the Haskell Minnow. It has acquired the nickname the “Giant Haskell” because it is 10 inches long and twice the size of the next largest known Haskell lure.

It is half-surprising Basore says he has never owned the Giant Haskell. But he said he has possessed a medium-sized and small Haskells, one of them dating to 1859. “Super rare,” he said, only 15 known in existence, and he has had two of those.

Although Basore has conducted instructional schools for kids, given seminars and lectures, and works diligently to pass on knowledge and lessons to young people, he wonders if he and others like him are becoming anachronisms. Up-and-coming generations don’t show the interest in the sport’s history he and his contemporaries do, Basore said.

“They’re an art form,” Basore said of lures. “They are artistic. And they are things you can use, for the better. But I don’t know if they’ll always be worth something. They’re (old collectors) dying.”

Old lures provoke nostalgia

Bell, in Wisconsin, sells new lures, but his specialty, setting his business mybaitshop.com apart, he believes, is selling old and “vintage” lures, among those 50,000 he sells annually.

“It’s growing,” said Bell, 51, with many demonstrating a nostalgic bent. “I want to attract new and young collectors. My true passion is the history of the companies, the lure manufacturers. Dan’s been very helpful with that. Generations die out, but I’m trying to create a resource that will last.”

Basore owns boxes containing unopened lures from a century-plus ago. He has researched the history of the lure-maker and the manufacturer. The South Bend Bait Company, located in Notre Dame’s hometown, and the Creek Chub Bait Company of Garrett, were prominent Indiana lure manufacturers.

Basore can pour out historical information about the companies, recognize their lures, and evaluate prices of those for sale on line. He knows rarity. South Bend opened for business in 1906. One online site site has an older company lure for sale for $225.

Creek Club dates to 1916 and produced a famous lure called The Wiggler. Online searches show the wooden lures, some new, with their boxes, are available. One advertised at $135 is so shiny it is described as “Stunning!”

While that doesn’t represent big bucks, if someone would like to jump-start a collection, or improve its stature, Basore can be the man to see. Periodically, over the years he has swapped multitudes of lures to the same dealer for new automobiles. Naturally enough, the man who signs his correspondence “Lures Truly,” has vanity plates on his vehicles flashing such messages as “Lures.”

Bell is hardly the only one who glances at antique lures and reads history. The National Fishing Lures Collecting Club was established in 1976 and Indiana is a stronghold. Every other year, the club’s national collector’s convention is held in Fort Wayne.

This is a non-profit outfit and its mission announces a goal to preserve fishing tackle and provide education. The convention is not an open-doors event for anyone, but is for members and their guests.

Basore said he has displayed goods since the first convention in 1982 when he showed at four tables, and he is a regular.

David Saalfrank, an organization vice president and co-host of this year’s convention, has been “chasing old lures since 1986,” and said “nostalgia is the biggest part of it. Some think they’re going to make a living at it, but probably only three or four guys do.”

Saalfrank said he is not in collecting to make money.

“If I’ve got a lure I really like, I don’t care (how much it might be worth),” he said.

Saalfrank said lure collectors can “have something perfect and rare” while it being somewhat inexpensive. “It’s an affordable hobby,” he said.

Older, long-time collectors like Saalfrank — he is 76 — and Basore, are conscious of giving back and spreading knowledge. Basore, he said, has “publicized research and come up with as much information on companies as anyone in the club.”

Spreading his knowledge

Basore has collected fishing lures (and memorabilia) for nearly 65 years. First he learned his stuff, then he spread his knowledge to others through lectures and displays.

Although Basore can recite a story about Cleopatra’s man-servants helping out manipulating her catches through her lures, the oldest lures Basore has possessed, coming from Alaska, go back 2,000 years. Cleopatra? Ancient Alaska? The line for lecture tickets forms on the left.

Chauncey Niziol, a long-time outdoors writer and broadcaster in the Chicago, and a Basore friend, likens his collection to a sort of “Smithsonian” Institution for fishing.

Basore does see himself as essentially a museum custodian, the conduit of history.

“I’m a temporary caretaker of all this stuff,” Basore said.

The makers’ stories and their lures.