The Speaker/Otte/Rieker/Koop family gathered during the Hoosier Homestead Award Ceremony at the Indiana Statehouse in March.

Submitted Photo

The Cummings family gathered together next to one of their tractors.

Submitted photo

The Durham family gathered during the Hoosier Homestead Award Ceremony at the Indiana Statehouse in March.

Submitted Photo

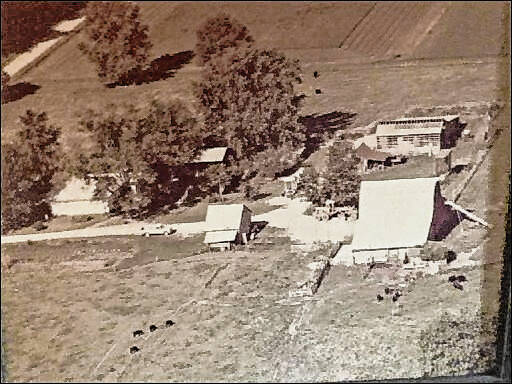

This is a 1970 photo of the homeplace owned by Gregory and Julie Rieker. The family home sits across the road from the Speaker/Otte/Rieker farm ground.

Submitted Photo

A recent photo of the homeplace owned by Gregory and Julie Rieker. The homeplace was owned by Julie’s grandparents, Raymond and Evelyn Otte, and her parents Jerry and Monica Otte. Gregory and Julie now own the property.

Submitted Photo

The Cummings family farm and their chickens from 1924.

Submitted photo

Silos at the Durham family farm.

Jared Reedy | The Tribune

An expansive field at the Durham family farm. The family focused mainly on producing grain after retaking operations over from local farmers who had rented the land.

Jared Reedy | The Tribune

The basement of the Tatlock family log cabin.

Jared Reedy | The Tribune

The kitchen of the Tatlock family log cabin.

Jared Reedy | The Tribune

The upstairs of the Tatlock family log cabin.

Jared Reedy | The Tribune

Other than Abraham Lincoln’s single-story log cabin, the Tatlock’s log cabin is the oldest story-and-a-half log cabin in Indiana.

Jared Reedy | The Tribune

In the words of famous author, Margaret Mitchell, of “Gone with the Wind,” “The land is the only thing in the world worth working for, worth fighting for, worth dying for, because it’s the only thing that lasts.”

Many Hoosier farmers can attest to these same words as hard work and sacrifices had to be made for their families to keep their farmland for many generations.

Through generations of hard work and significant contributions to Indiana’s agriculture many families are awarded the Hoosier Homestead Award for operating a farm for multiple generations.

To be named a Hoosier Homestead, farms must be owned by the same family for at least 100 consecutive years and consists of more than 20 acres or produce more than $1,000 of agricultural products per year. The award distinctions are centennial, sesquicentennial (150 years) and bicentennial (200 years).

Four Jackson County families recently received Hoosier Homestead awards and were honored at the Statehouse.

Speaker/Otte/Rieker

Gregory and Julie (Otte) Rieker were the lucky family to receive two homestead awards, one for 150 years for one farm and 100 years for a second.

Just across the road from their rural Seymour homeplace is the 40-acre farm that won the 100-year award. That farm belonged to the Speaker/Otte/Rieker families.

John Henry Speaker was born in Bavaria, Germany, in 1851 and immigrated to the United States in 1854. Speaker purchased the property in 1886 and then transferred it to his son William John Speaker who married Emma Behrman. She was an aunt to Evelyn Behrman Otte.

The property was transferred to Raymond and Evelyn Otte in 1947, Julie’s grandparents, before Julie and Gregory purchased the property in 1989.

The property has continued to produce corn, soybeans and alfalfa over the years.

Just south of the 40-acre farm is the second farm that won the 150-year award. It belonged to the Koop/Otte/Rieker family tree.

Louis Ludwig Koop acquired the ground in 1867 and upon his death in 1881 it was passed to his son, Louis. Louis and his wife Anna. They passed the farm along to their three sons, including Fred Koop in 1920. Fred sold the property to his uncle Raymond and Evelyn in 1966. Gregory and Julie purchased the farm in 2005. Family lore says at one time there was a small hog farm that existed on the grounds.

As families came and went much of their total land, which is more than 200 acres, was split into sections. Over the generations, the families found ways to connect the grounds much like puzzle pieces.

“They worked really hard to keep these properties in the family,” Julie said.

Owning land of multiple generations often comes with memories, Julie said she fondly remembers many Christmases with her grandparents, Easter egg hunts, running cattle and butchering days with her family members.

“We still have some of the old butchering equipment that they used in the 1800s,” she said.

Gregory said they have been able stay successful thanks to the hard work they have learned from those who have worked the land before them.

“These families stuck together and were able to move things forward for a better life,” he said. “It’s all about hard work. Our kids spent a lot of summers working on the farm and they know what hard work is.”

Julie said hearing her family’s stories of sacrifice has made her grateful to still stand on the same land as her ancestors.

“I can walk out and touch the same dirt that my grandmother and great-grandparents touched,” she said. “I think my parents and grandparents would be ecstatic with these awards because they knew how important it was to keep the farm in the family.”

As for Gregory and Julie’s children, Christoph, Steven, Zachary and Katrina Wethington, Julie said they all enjoy coming to a homeplace filled with history, peace and family love for future generations.

“I thank God every day that we were able to keep it in the family,” she said.

Cummings

“I thought about my grandpa and dad,” said Don Cummings while reflecting on receiving their Hoosier Homestead Centennial award.

Discussing the “good old days” is a popular phrase that gets thrown around without much thought. Cummings recalled what his grandpa would say in reference to this concept: “Things weren’t so good when things were frozen.”

Without running water and electricity, there was plenty of hard work needed from generation to generation to get jobs done. Cummings’s grandpa experienced the emergence of technology and saw the earliest telephones before electricity was invented. Without these modern-day conveniences, the family made use of every resource they had.

His grandpa bought the rural Seymour farm back in 1924 after World War I and when he died, the farm went to Cummings’s father. Although being a farmer wasn’t initially in the plan, his father took up the mantle. This meant that Cummings didn’t grow up on the farm, but witnessed aspects of farm life regardless because his father was an agricultural teacher.

While their farm had cows, pigs, goats, sheep and chickens, that’s not what they usually ate. Instead, they would hunt for wildlife. Given one bullet, they could shoot a rabbit and have a meal.

Their farm animals had purposes outside of providing meat such as wool and eggs. These products could then be sold or turned into something else.

While receiving the award, Cummings looked around and realized that many of the farmers now are well into their years and don’t farm themselves but rent their land out. Also referred to as cash-rent tenants, the Cummings family are farmers who rent their land out to local farmers for a fixed amount of money and land.

“The dollar talks,” Cummings said, wondering about the future of farming. Specifically, how other countries like China are interested in buying American farmland.

While this concern is palpable for many farmers, the passion of these families can be recognized throughout the generations that stand on these lands.

Durham

Glenn Durham said his grandpa originally bought their land, presently 86 acres, and used it to grow produce — predominantly watermelons. When his father got out of the army, he returned to the rural farm southwest of Brownstown and helped Durham’s grandpa raise cattle and grow produce and grain crops.

“Dad quit farming in the mid-50s or early ’60s, so we rented the land out to some local farmers,” Glenn said. “We helped them in the summertime, planting stuff and doing a lot of stuff for sweet corn for the canning factory in Brownstown.”

Glenn said once the Durham family took back over operations, they focused mainly on producing grain.

Don Durham, Glenn’s brother, said, “(Farming) technology has advanced so much, it’s kind of like the internet — it’s just exploded; year after year they come out with new technology. Combines and tractors can keep a record of what they’re doing and when they’re doing it. GPS is paramount now. The technology is just amazing. Now they have drones that come in and spray. I don’t try to keep up with it; just abide by it and go from there.”

When asked what advice he would give people interested in farming, Don joked, “Don’t.”

Glenn and Don agreed that farming was hard work but extremely rewarding.

Glenn added, “It seems like there’s more and more opportunities, especially for a lot of smaller producers. It doesn’t take a lot of acreage to make a living … But with the produce — at times — it’s gotten too big-scale operations, especially if you’re dealing with large corporations like Walmart or Kroger.”

Don said, “It’s tough (to enter) because it takes so much capital to get into it … If you’re persistent and really have the initiative, you can get in and you can make it. It ain’t no 9-to-5 job, you know; it’s 24/7 just about.”

Kaye Durham, Glenn’s wife, said farming is a gamble because of the weather.

“You don’t know how your crops are going to do,” Kaye said. “Sometimes you have good years and sometimes you have bad years, and that’s kind of scary.”

Tatlock

According to William Tatlock, the land of the Tatlock family farm was actually established by the Russells (of the Russell Chapel Church) in 1863. The Russells lost to the land to a tax sale.

William said his great-grandfather Walter Tatlock of Washington County took over the farm in March of 1888 from John and Emily Kitell. Walter’s son and William’s father Kerry Tatlock, a locally renowned coon hunter, took over operations of the farm in September of 1920. Walter and Kerry had previously cleared much of the land with mules. Kerry passed away in January of 1970.

The land was then rented out for a good majority of the next few decades.

William Tatlock took over the farm from his uncle Robert Tatlock in 2010, though Robert and his wife Jean still lived on the property.

The log cabin on the property is a story and half, and other than Abraham Lincoln’s single-story log cabin, the Tatlock’s log cabin is the oldest story-and-a-half log cabin in Indiana, William said.

“The ground has a continuous water source, a spring, running 24/7, 365 days a year,” William said.

The state distributes Hoosier Homestead Awards twice a year. The next round of winners will be announced during the Indiana State Fair in early August.

Tribune reporters Erika Malone, Jared Reedy and Chey Smith contributed to this story.