Larry Bothe, left, curator of the Freeman Army Airfield Museum in Seymour, talks to Joe Schneid of Louisville, Kentucky, while on a tour of the museum Aug. 30.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

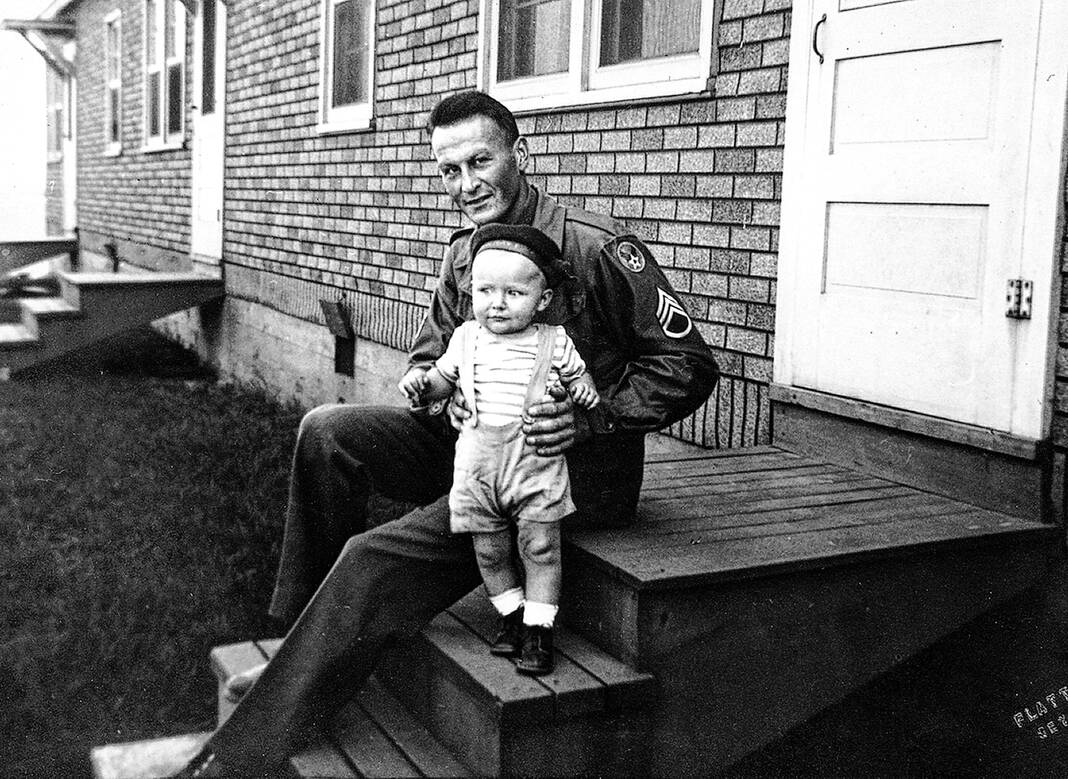

James R. Schneid is pictured with his young son, Joseph Schneid, at the Ridgeview housing unit at Freeman Army Airfield in the 1940s.

Submitted photo

In early August, Joe Schneid of Louisville, Kentucky, stopped by the Freeman Army Airfield Museum in Seymour on his way to Indianapolis for a granddaughter’s wedding, but it was closed at the time.

Submitted photo

Larry Bothe, center, curator of the Freeman Army Airfield Museum in Seymour, talks to Jerry and Ann Yates and Sandra and Joe Schneid as they visited Aug. 30 from Louisville, Kentucky.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

James R. Schneid is shown in a link trainer.

Submitted photo

Sandra Schneid, Ann Yates, Jerry Yates and Joe Schneid, all of Louisville, Kentucky, look in display cases at the Freeman Army Airfield Museum in Seymour as curator Larry Bothe takes them on a tour Aug. 30.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Larry Bothe, left, curator of the Freeman Army Airfield Museum in Seymour, takes Joe and Sandra Schneid and Ann and Jerry Yates of Louisville, Kentucky, on a tour of the museum Aug. 30.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Shortly after receiving an email with “first baby born at Freeman Field” in the subject line, Freeman Municipal Airport Manager Colin Smith replied.

In the body of the email, Joe Schneid typed “In case anyone ever asks, ‘What ever happened to the first baby born at Freeman Field?’ 80 years ago, I was the first baby born at Freeman Field on Sept. 9, 1943.”

“I instantaneously became curious,” Smith said. “My curiosity just spoke, and I think history is just as important as the future. Things that happened just have the same meaning as things that are to come.”

Schneid also included the Freeman Army Airfield Museum in the email.

“When you gave that information to us, I wanted to hop on it instantly,” Smith said to Schneid during a visit to the airport on Wednesday.

“And you did,” Schneid said, smiling.

“There’s so much history of the city of Seymour and the airport, so I knew someone out there would be very intrigued about the story,” Smith said.

Larry Bothe, curator of the museum, was as intrigued as Smith and his administrative assistant, Victoria Taylor.

“I thought it was pretty neat,” Bothe said of looking at the documents and photos and reading information in the email. “I was more interested in his father. We’re really interested in gathering information about people who were actually stationed here.”

One of the documents is an article from the airfield’s newspaper announcing the first baby born at the Freeman Field station hospital being the first to be baptized in the post chapel. Ten days after being born to James R. and Margaret A. Schneid, Joseph was christened with Chaplain Daniel A. McGuire officiating.

James, a native of New York, was attached to the 35th group at Freeman Field.

“He was in the Army Air Corps,” Joe said of his father. “He met my uncles, my mother’s brothers, in the Air Corps, and they were from Ramsey, Indiana. They were all barnstormers. They flew planes back before it was the FAA. They just got in them and took off. In fact, my uncle owned an airport in Clarksville, Indiana, for years until about 1956 or so. He sold out to someone that was going to put in a shopping center, and he moved to Florida.”

One time, James went home with Margaret’s brothers to Ramsey, and that’s how he met the woman who became his wife.

In the military, James worked in intelligence. Joe said he’s not sure how long his father served in Seymour, but he graduated from link trainer school at another air base and served at several other locations in the area.

“He was sent overseas right after the war ended, so he got to spend seven or eight months over there, more like a vacation,” Joe said. “It showed him visiting different places. I don’t know what he did over there as far as military job, though.”

After the war, the Schneids bought a house in New Albany and lived there until 1957 when an oil company bought it and others around it to put in a filling station. Then the family moved to Louisville, Kentucky, which is where Joe and his wife, Sandra, live today.

“After he got out (of the military), he went to work for BFGoodrich and retired from there,” Joe said of his dad.

Joe followed in his father’s footsteps and served in the military. After high school, he attended Coyne Electronics School in Chicago, Illinois, and then worked for National Cash Register Co. for a couple of years. Then in April 1965, he was drafted by the U.S. Army and was required to serve at least two years.

“I went to basic training at Fort Knox, and they had a dream sheet. You can fill out this sheet ‘What do you want to do in the service?’” Joe said. “Since I had already worked for the National Cash Register Co., for a couple of years, I put down office machine repair. In their infinite wisdom, they assigned me as a sewing machine operator and sent me straight out of basic training to Fort Lee, Virginia, to operate a sewing machine.”

Schneid said that was unusual because most people went from basic training to a school to learn how to do a particular thing.

“When I reported in, the sergeant looks at my paperwork and he said, ‘You’ve got awfully high scores. Can you type?’” Schneid said. “I said, ‘Well, not really. I had half of a year of it in high school,’ and he said, ‘Oh, you’ll learn. How would you like to be a clerk?’ That’s what I did the rest of the time I was in the service. I was a clerk.”

During his time in the Army, he spent eight months stationed in Thailand. After he got out, he went back to work for NCR. In 2000, he retired from there after 38 years of service.

Schneid’s uncles were in World War II the same time as his dad, and two of his sons served, too.

In terms of going back to the place where he was born, Schneid said about 20 years ago, he stopped by the Freeman Army Airfield Museum and thought he needed to send some information and pictures to them.

His next visit wasn’t until early August of this year, but at the time, the museum was closed. He, however, was able to meet with Taylor, and she arranged a private tour of the museum for him.

That’s why he returned Wednesday.

“The fact that I’m the first baby born (at the airfield), I’m turning 80 next month, this is probably something to carry on after I’m gone,” Schneid said. “I’m going to leave it with them and pass it on to somebody else.”

A couple of the documents have an interesting story. They are Schneid’s birth certificate and a letter he received from the Jackson County Health Department in early July 1991. At that time, he needed a copy of his original birth certificate for security clearance while working on a COMTEN communications processor at Fort Knox.

His name is listed as Joseph Freeman Schneid. According to the health department letter, his middle name was different from the baptism record, which shows it being Michael.

“My dad was asked by the officers to name me Freeman. My dad refused,” Schneid said.

The airfield was named after Capt. Richard Freeman, who was killed in a B-17 crash in Nevada in early 1941 before World War II started and Freeman Field was established.

“After all those years, it still made my dad mad when he found out because they did that behind his back,” Schneid said. “I had to fill out paperwork and stuff to get it corrected.”

Schneid said he appreciates the communication with Smith and Bothe to get the documents and photos submitted to the museum.

“I just want to say how gracious everybody here has been — really nice,” he said. “(Bothe’s) questions got me looking closer at the stuff I had.”