Even in April, the mountains alongside the Alaska-Canada Highway are coated in snow, and some remain so year-round.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

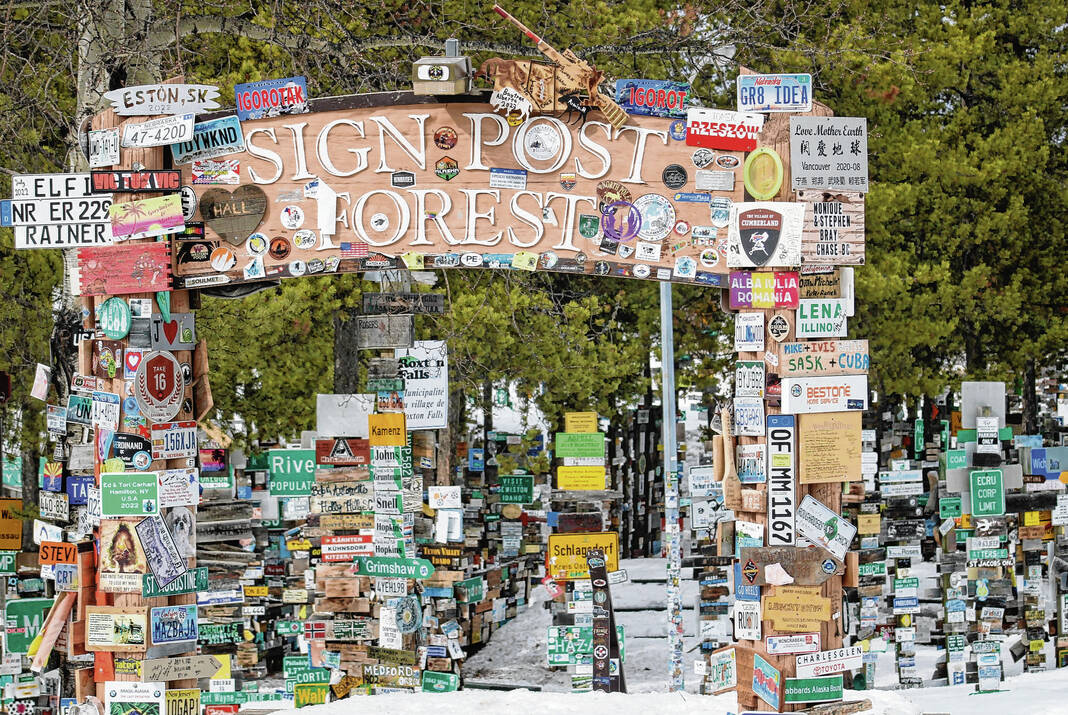

One of the most famous landmarks along the Alaska-Canada Highway is the aptly named Sign Forest in Watson Lake, Yukon Territory.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

This guy may have been the leader of a pack of moose in Anchorage.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Moose populate the far north. This group was hanging out in Anchorage at the end of the 4,012-mile drive.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Some First Nations tribal members in Canada have distinctively decorated homes along the highway.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

The sign marking Mile Zero at the southern end of the famous Alaska-Canada Highway in Dawson Creek, British Columbia.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Possession of marijuana is legal throughout Canada, and shops selling the weed abound in communities.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

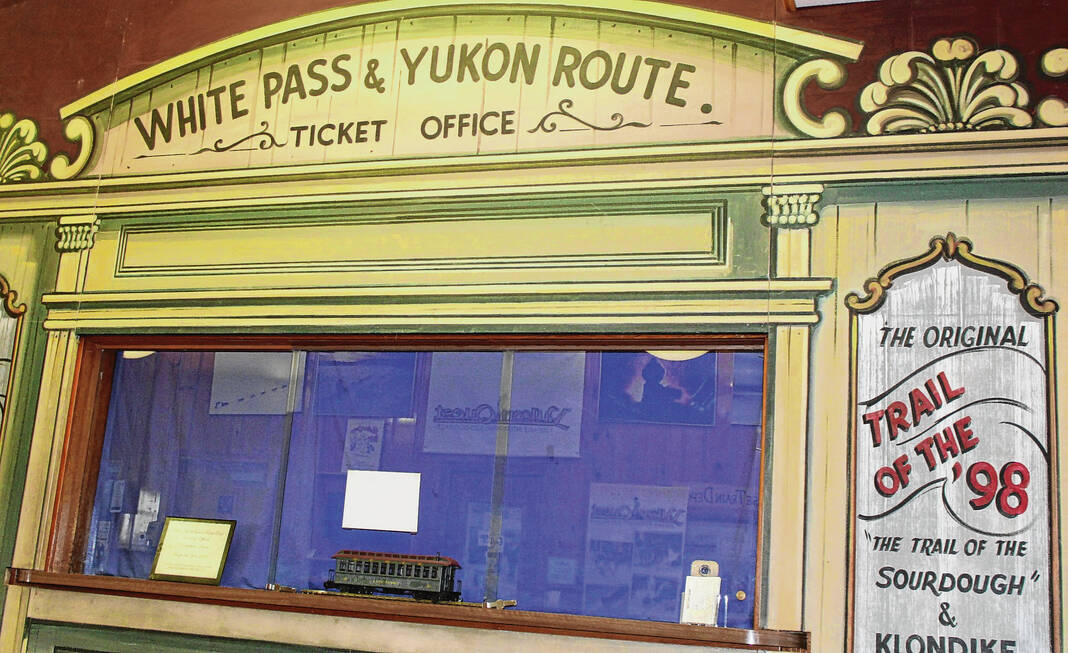

The old train station in Whitehorse, where the first workers arrived to begin construction of the Alaska-Canada Highway in 1942.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

For many years, driving the Alaska-Canada Highway has been commemorated as a rough bit of travel, and motorists completing the approximately 1,500-mile distance of the road slap bumper stickers on their vehicles reading “I Drove the Alaska Highway and Lived.”

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

The essence of the journey was summed up in a flavorful, cartoonish bumper sticker reading “I Drove the Alaska Highway and Lived.” I did both.

Skipping over those who traveled west for a new life via wagon train, credit author Jack Kerouac for instilling the romance of the road in the psyche of Americans in the 1950s.

Speaking for a generation and those who followed, Kerouac instilled the itch to point an automobile where it had never been to see what was out there through his energetic book “On the Road.” Americans put the horrors of World War II behind them and embraced freedoms invited by a nascent interstate system.

Combining open-mindedness toward open road with the lure of the north took me on a 4,012-mile odyssey from southern Indiana to Anchorage, Alaska. While hoping against too much lingering winter weather (not to be) over a Tuesday-to-Tuesday stretch of the April calendar, I tested my little compact car.

I conveniently stowed the adage of my old friend, Bradford Washburn, a scientist and mountain climber who mapped Alaska’s Denali and Mount Everest, among other achievements, who once commented a trip is not an adventure until something goes wrong.

The route: Southern Indiana through Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Paul, Minnesota, Fargo, North Dakota, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Grand Prairie, Fort Nelson, Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, on to Anchorage.

Much of the way traversed most of the 1,500-mile Alaska-Canada Highway, built in 1942 as a gesture of cooperation to facilitate troop movements during World War II.

Initially, this gravel highway was barely kinder to cars than the Oregon Trail was to those covered wagons. Horror stories flourished. Flat tires were a given. Collisions with wildlife. It was the wild, wild west on wheels.

Over the decades, though, the road has been smoothed, straightened, nicely paved and regularly repaved following brutal winters. The equivalent of ghost stories told around the campfire are more mythical than accurate now.

Yet the No. 1 rule remains the admonition to top off the gas tank whenever a station is available because not everything is open all the time. Gasoline is the primary need as well as fuel for the driver, and it takes good planning to arrange where to sleep.

Onward, through wild Manitoba, wild Alberta, wild Saskatchewan, into wild British Columbia, heading through the wilder Yukon, alighting in Alaska, The Last Frontier.

Day 1

It made sense to begin with a full tank, so the first gas stop was in Indianapolis. The temperature was in the 50s, and I ran into a thunderstorm, though it quickly passed. I was in the Eastern time zone, but as I headed west and north, I kept gaining time. Alaska has its own time zone, four hours earlier than Eastern.

My lovely dinner was at a convenience store. Made it easily to St. Paul.

Day 2

It was 35 degrees and misting, and Interstate 94 toward Fargo had many icy patches and some iffy snow patches. I began seeing alert signs saying Interstate 94/Interstate 29 in Fargo was closed. Interstate 29 was what I sought, turning north to Grand Forks and the Canadian border.

Having left my United Nations interpreter behind, I believed the intersection of the highways was closed. But when I got there, the road appeared open. It wasn’t snowing, and the sky was blue, though it was extremely windy and snow blew across the road.

I plunged ahead. Mistake. And apparently illegal, as I discovered after I got stuck at the side of the road. A road maintenance truck driver said, “What are you doing out here?” He called the state police. The trooper was very angry, gave me a $250 ticket for driving on a closed road, told me I could not proceed and called for a tow truck after she energetically failed to dig me free. Almost got my money’s worth out of her effort.

The affable tow truck guy instructed me to trail him the 20-something miles back to Fargo. The trooper followed but then pulled up next to me and threw a fit, yelling I couldn’t be on that road. That made no sense since we were in the middle of nowhere and I couldn’t go to Grand Forks. Was I supposed to stay in one place with no food?

In acknowledgement of Washburn, probably any time a car is involved in an adventure, it is a bad thing. The good thing is planning a very different return route, I never have to drive through North Dakota again.

Later, after informing friends I was stranded in Fargo a day, some reacted as if I had stumbled into a voodoo curse, sagely nodding, “It’s Fargo.”

Day 3

The authorities opened Interstate 29 at 7 a.m. to liberate me from Fargo. Plenty of snow along the side of the highway and irregular patches of ice on the highway. I thought the Canadian border check station was at Grand Forks. But no. I ignorantly drove along singing, “Oh, Can-a-da, where art thou?” It was way north of there.

I was fifth in line among cars at the border crossing. A separate truck lane was much longer. Mr. Customs Agent asked if I had any pets, marijuana or more than $10,000 in cash. Then he sent me into a building for further review anyway. A dozen people were quietly seated, reminding me of the Group W bench in the Arlo Guthrie song “Alice’s Restaurant.”

The agent at the counter glanced at my passport and abruptly asked if I was diabetic. She wanted to know if I had any medicinal insulin needles, which I did. She then examined them in the car and cleared me to go.

One of the first things I saw in Canada was a Tim Hortons doughnut shop. Tim Hortons is to Canada what Dunkin’ Donuts is to the United States, sugary and ubiquitous.

The story behind Tim Hortons is Tim Horton. An all-star National Hockey League defenseman between 1949 and 1974, primarily for the Toronto Maple Leafs, Horton founded the chain but died in a car crash at 44. In tribute to Horton, some of the establishments have hockey stick handles on the front door.

The second thing I saw in Canada was a vivid Subway sandwich shop sign.

Surely Alexander Mackenzie, Canada’s explorer of a magnitude equal to Lewis and Clark, who was the first to cross North American in 1793, would chuckle over the handy readiness of those fast-food places. He fended for himself in the wilderness.

When I filled the gas tank in Canada, I realized I had no idea how much I was putting in since the measurement was liters instead of gallons, nor how much I was paying since the price was in Canadian currency. Didn’t really matter. I had to gas up. I knew it was more than the $3.40 U.S. per gallon, which was about what I was paying in Indiana.

While pumping gas, a friendly Manitoba fellow took note of my license plate and waxed poetic about enjoying his one visit to Indiana, speaking highly of Indianapolis and the state’s cornfields.

Reached Saskatoon, making up for my lost day in Fargo.

Day 4

Fate brought me to my first Tim’s stop in Saskatoon. The doughnut store was attached to a gas station, and when trying to leave, I accidentally turned into the take-out lane, from which there was no escape.

I ordered two “chocolate topped” doughnuts, but the man said they did not have such doughnuts. Later, I learned this was a case of English not translating to English. It seems Tim Hortons does make my brand but calls them “chocolate dipped.” Saved me from a poor dietary choice.

Long-distance drivers often prefer their own tunes, popping in discs of preference. I winged it, switching radio stations to pick up local flavor and news.

While listening to Winnipeg and Regina radio, I enjoyed a couple of vignettes. An ad urged Canadians to take vacation advantage of new service flying from Vancouver on Fiji Airways. Fiji?

Transferring from Trans Canada 1 to the Yellowhead Trail (good highway name), I heard hosts ask listeners to relay their closest calls with wildlife.

One guy explained he was chased by a black bear at a remote helicopter airstrip in British Columbia. A young woman said she visited Australia with family when she was 5 and was punched by a Joey, a young kangaroo.

The road gradually narrowed to one lane in each direction with long gaps between civilization. However, each tiny town — and they were not even dots on my map — had a Tim Hortons and a Subway. Often, they were the only eating choices.

Edmonton, Alberta, home of the playoff-bound Oilers, led to multiple Stanley Cups by Wayne Gretzky, does have a street named after the greatest scorer in NHL history.

For those who dispute the concept of climate change, you’re wrong. One minute it was 60 degrees, another 47. I had cloud cover, snow flurries, hail and rain all in a day. Climate change was breaking out all around me.

Day 5

Snow was everywhere along the side of the highway along with evergreen trees and some birch and irregular patches of ice on the highway.

There were hardly any cars, regularly a few minutes between vehicles. This was outdoors playground territory, but the provincial parks passed were closed for the season.

More and more wildlife crossing signs appeared, warning of moose, caribou, elk, bison, even wild horses grazing. There were advisories, same as in U.S. states like Montana and Wyoming, that transporters of boats must “clean, drain and dry” to protect against invasive species.

The beginning of the Alaska Highway, or Al-Can, as it is frequently called, is in Dawson Creek, British Columbia. There is a very large sign heralding Mile Zero. The only other people around were a 30ish couple from South Dakota with their dog headed to Anchorage for three months to work in the travel industry on a first visit to Alaska.

Anyone going farther north is pretty much traveling parallel to one another. As the hotel operator that night in Fort Nelson, British Columbia, said when urging me to stop again on the way home, “There’s only one way out.” He made it sound like a version of the Hotel California.

Mostly, those warning signs about wildlife were false alarms. Some were shot through with holes, though with smaller bullets than Americans use.

Hints of human habitation grew sparser. Some roadside lodges were buried in snow. Many hotels were closed. Many restaurants were shut. Always gas up. Open lodges tempted food stops. Even Subway and Tim Hortons became rarer.

At one point, a highway sign announced there were “no road lines” ahead. Did they run out of paint?

I passed a handful of wild horses chomping on grass. Were they escapees from a rodeo? No moose. Then, over a span of about 30 miles, I came upon three groups of bison, 30 in one herd resting on a hill, 25 together and five in a third place. Four, really, with a fifth blitzing across the road left to right and barely seen out of the corner of my eye. Missed it by that much.

Periodically, the road returned to the condition of days of yesteryear with 100-yard stretches peeled down to gravel. If you were going the speed limit of 100 kilometers per hour (62.5 mph), you would experience the same sensations offered by airplane turbulence.

A friend from Alaska said many years ago he drove the Al-Can nine times between Colorado and Alaska.

Once, he was snowbound in Destruction Bay. A bar was thrown open for free drinks, and he sat in on a poker game. Then one guy had a seizure and needed an emergency medivac to a hospital. That comes under the heading of adventure.

Day 6

I passed a Watson Lake “Gateway to the Yukon” sign, so worn it could barely be read. It might not have been painted since the 1896 Gold Rush began.

Watson Lake is a legendary must-stop on the highway. Not because it has a marijuana shop on the main drag (marijuana was legalized in Canada in 2018) but because it is home to the Sign Post Forest, an artificial forest. Oh, there are trees there, but they are decorated, covered by some 80,000 signs naming places around the world erected by passersby.

The sign forest goes all the way back to the beginning. An American soldier working on construction of the highway put up a directional marker to his hometown of Danville, Illinois, 2,835 miles away. There are now so many signs the only way to read them all would require moving to Watson Lake. Still, any driver can add his own.

It popped into memory that in the 1980s, I often saw “I Drove the Alaska Highway and Lived” bumper stickers on cars, and I wondered if they still existed. Sure enough, they were selling in a Watson Lake store. Now, I own one.

Toad River Lodge was open. Besides gas and food, there is a gift shop selling a sweatshirt displaying a clever slogan: “Don’t Pet the Fluffy Cows.” Those “cows” are the nearby bison.

Entering the Yukon was a rush. It was the last province or territory before Alaska. The Yukon is proud of itself, a land of mystique, the way Alaska is for Americans. As I cruised into snow flurries, I saw blue signs on the side of the road proclaiming, “Yukon: Larger Than Life.”

This was my sixth visit to Whitehorse, the Yukon capital, dating back 40 years. The entire population of the Yukon was about 25,000, with Whitehorse accounting for 15,000 people, when I first saw it. Now the numbers are approximately 44,000 and 25,500.

A downtown Whitehorse statue of a prospector accompanied by his trusty dog is “dedicated to all those who follow their dreams.” It is a marvelous sentiment and a striking sculpture. In town, more definition-of-place slogans are displayed, such as “True North” and “No Ordinary North.”

My hotel, which I had previously paid for, charged my credit card again (company fixed it) and the desk clerk gave me the key to the already-occupied wrong room. The hallway smell on the second floor was thick with eau de marijuana.

The inhabitant of the room I woke was from Fairbanks originally and was moving home to Alaska. While we spoke, a guy walked by wearing a sweatshirt heralding the Salty Dawg Saloon in Homer, Alaska. Hours later, I bumped into the South Dakota guy at a breakfast place. All road travelers to Alaska go through Whitehorse.

Almost immediately saw two Tim Hortons (making 25) there and two Subways (making 30). Tim’s makes sense. Did the government buy stock in Subway?

Day 7

I scheduled a down day in Whitehorse because of my fondness for the town and to see friends, dining at the home of Frank and Anne Turner.

Frank Turner, a past champion of the Yukon Quest 1,000-mile dogsled race, and Anne have lived in Whitehorse for a half-century after coming from Toronto. They live right off the Alaska Highway.

When Frank saw the flimsy tires on my trusty steed, he said, “You ought to know better than that.”

The Turners marvel at many changes in Whitehorse. The highway is much smoother compared to the old gravel days. There has been more tourism since the 1980s. Frank said there used to be more pickup drivers carrying loaded weapons and open cans of beer.

The disaffected loner-settler-outdoorsman stereotype from elsewhere in Canada is a passe demographic.

“We’ve got four sushi restaurants,” said Anne, who has worked in community activism. “We have a mosque. Sixty languages are spoken here.”

Day 8

It is open, breathtaking land going north from Whitehorse to Alaska, rugged snow-coated mountains and hardy trees marking the passage through Destruction Bay and Burwash Landing. Even the highway was tougher with more bumps.

When signs warned of rough road, they weren’t kidding. There were fissures, or frost heaves, prepared to toss the car side to side. Gravel worked itself into wheel wells and ricocheted around, sounding like shaken dice.

The U.S. border seemed deserted. No other cars were around. The border agent said the next 43 miles would be dicey, which was basically a synonym for icy. It was 424 miles to Anchorage.

Twice I drove into falling snow, near Mentasta, and again near Chickaloon. In some places, the wind was so strong it created swirling snowlike dust devils.

Entering Anchorage, the end of my road, snow berms from a hard winter were piled feet high everywhere even though the calendar was weeks past the start of spring.

Promptly, I came upon four moose trotting around, foraging for grass and plants beginning to poke through some melting snow. They had survived a 100-plus-inch snow winter, not among the casualties on 300-plus casualties declared on the nearby Glenn Highway, and now were trying to survive spring.

Just as I had done on the Canada and Alaska highways which had not yet received the message a new season had arrived.