The Siefker family received the Hoosier Homestead Award during the 2022 Indiana State Fair in Indianapolis. From left are Indiana State Department of Agriculture Director Bruce Kettler, MerriBeth Everett, Grant Siefker, Steven Harrell, Jackie Sue Harrell, Judy Pallatin, Don Benter, Heidi Mackos, Josh Rubin, Michelle Rubin and Indiana Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch.

Submitted photo

Martin Siefker built this home at 2286 N. County Road 500E, Seymour, in 1887, and it’s still in the family today.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Beef cattle continue to be raised on farmland owned by the Siefker family.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Beef cattle have been raised by the Siefker for a long time.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Siblings Grant Siefker and Heidi Mackos own a majority of the farm that has been in the Siefker family since 1848.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

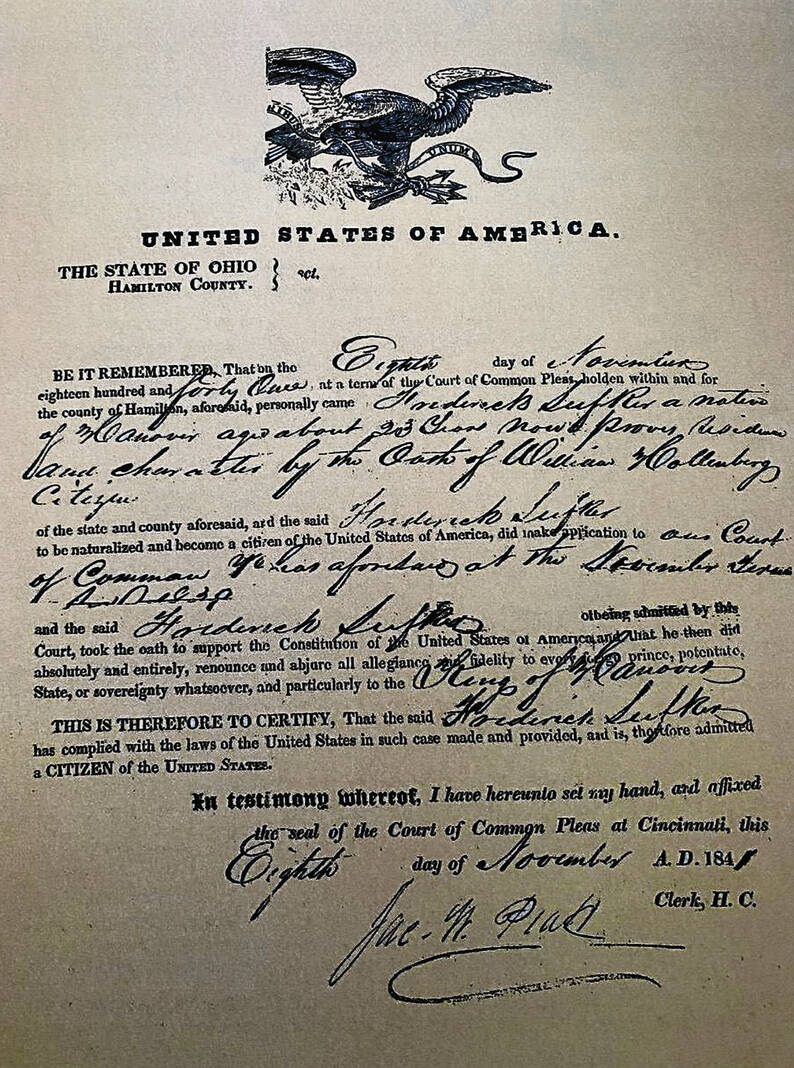

Frederick Siefker emigrated from Germany to Ohio and became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1841. He then traveled to Jackson County in Indiana and purchased 100 acres of land, which he cleared, built a house on and farmed the ground.

Submitted photo

Jackie Sue Harrell has become the self-proclaimed genealogist of the Siefker family.

In 1960, two of her cousins put together the family’s genealogy. In 1980, one of her father’s brothers and his wife put together some more family history. Twenty years later, a cousin took it over and kept information updated.

Then it laid dormant for a while until 2014 when Harrell stepped up.

“It got to the point where nobody was keeping it up, and I thought, ‘Well, this can’t happen,’ so I just arbitrarily decided to take it over,” she said.

That dedication and keeping a farm in rural Seymour in the family since 1848 resulted in the Siefkers being eligible for the Hoosier Homestead Award.

To qualify for the honor, a farm must be owned by the same family for more than 100 consecutive years and consist of 20 acres or more or produce more than $1,000 in agricultural products per year.

Based on the age of the farm, families are eligible for three different distinctions: Centennial Award for 100 years of ownership, Sesquicentennial Award for 150 years or Bicentennial Award for 200 years.

The Siefkers received both the Centennial and Sesquicentennial awards and were one of 106 Indiana family farms recognized at the 2022 Indiana State Fair in Indianapolis by Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch and Indiana State Department of Agriculture Director Bruce Kettler.

Since the program’s inception, more than 6,100 families have received the award. Often, a Hoosier Homestead farm is easily recognized because most recipients proudly display their awarded sign on their property.

Harrell, who now lives near Southport, said it was really neat for several family members to attend the ceremony.

“The family was really tickled about it,” she said.

She submitted the Hoosier Homestead Award application, and one of the current owners of the farm at 2286 N. County Road 500E, Grant Siefker, received confirmation that the family was chosen.

“I’ve tried to keep the records of the births and deaths and marriages and so forth since me and my first cousins, our grandparents to the present,” Harrell said. “Because I was doing all of that, my cousin, Judy (Pallatin), who is Grant’s aunt, she asked me if I would help her in gleaning the information needed to fill out the application for Hoosier Homestead, and so I said, ‘Sure, I’ll do that.’”

After a trip to the Jackson County Recorder’s Office in Brownstown, they got the deeds that transpired since their great-great-great-grandfather, Frederick Siefker, settled the land.

“He emigrated here from Osnabrück, which is in the province of Hanover in Germany,” Harrell said. “He became a naturalized citizen of the United States in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1841. He then traveled from Ohio to Jackson County, Indiana, and he purchased 100 acres of land, which he cleared, built a house on and he farmed that ground.”

He acquired the farm in 1848 and passed it on to his son, Martin Siefker, in 1887.

“It turned into Siefker’s Sorghum Mill, which was run by his son, John Siefker, and continued by John’s son, Walter, who is my daddy,” Harrell said.

The original house on the property unfortunately burned, and Martin built a two-story brick house for his wife, Elizabeth, and their family.

“That two-story brick house is still standing,” Harrell said. “(Judy’s) middle daughter and son-in-law (Michelle and Josh Rubin) now live in that house and they’ve purchased it. While Grant and his sister (Heidi Mackos) still own the majority of that farm, they did sell the house and the little bit of land around it to Grant’s cousin and her family, so there’s still a Siefker descendant living on the farm in that house that Martin Siefker built.”

When Martin died, the farm went to his widow, and then she deeded a portion of it to her daughter, Minnie.

“She married a VonDielingen. Her three sons, which were part of the Siefker family, they had it for a while,” Harrell said. “Then Martin and Elizabeth’s grandson, Judy’s dad, Henry, and his wife and Judy’s sister and two brothers purchased the farm.”

That was in 1947, and they mainly planted corn, wheat and soybeans and raised beef cattle.

“That’s what it has been over the years,” Harrell said. “I think there was somewhere that stated that Frederick also planted apple trees.”

After Henry died in 1980, the farm went to his wife, but she left part of it to her son, Michael, in 1995.

“He followed his dad’s footsteps raising corn, wheat, soybeans and beef cattle,” Harrell said.

Michael’s mother remained in the old brick house, while he and his wife built a more modern home to the south. Michael, who is Grant and Heidi’s father, farmed the land until he died in 2009.

After Michael’s mother died, he rented the brick house for a while until the Rubins purchased it.

“They have restored and modernized the house, but it still looks much the same,” Harrell said. “They have done a lot of updating the kitchen, the bathroom, that type of thing. They are going to add, I think, a dining room and another bathroom. They have two sons and one daughter, and they just love the house.”

While Harrell didn’t live on the farm, she said she spent a lot of time there growing up.

Her and Judy’s fathers were really close, and the two cousins were 11 months apart and grew up like sisters, Harrell said.

“There’s a beautiful curved banister in that house,” she said. “When you walk in the front door, it’s right in front of you because it’s beside the stairs that go up to the two bedrooms upstairs. Judy and I, and I’m sure her brothers and probably any kid that lived in that house, had slid down that banister. Her mom wasn’t always really thrilled with having anybody slide down the banister.”

Judy and Jackie also learned to ride bicycles on the farm. Michael was behind Judy holding the bike, and Dave was behind Jackie.

“We went off through the farmyard there out toward the barn, and we were pedaling and I remember saying (to Dave) ‘Are you still there?’ I wanted to make sure he was still holding on,” Harrell said. “Then something made me turn around, and he was gone and I was pedaling. I was riding a bike, and Judy did the same thing, so that’s a wonderful memory for me and Judy that we both learned to ride a bike at the same time.”

Harrell also remembers climbing up in a hayloft in a barn, riding at least one horse, watching Judy’s dad milk cows and shelling popcorn by hand.

“In the driveway, which was always dirt and a little bit of gravel, with a stick, we would make little roads and mark off roads and we’d stack up rocks to build little houses,” Harrell said. “We grew up poor, both of us. Our families didn’t have a whole lot of money, and so we always didn’t have all of the latest toys and things like that, so we had to make do with what we had and use our imagination. I just had so many fun times out there.”

Today, Harrell said Grant rents out the farmland, and there are still cattle on the property.

“It’s just an honor to carry that on, really,” said Grant, who lives in Indianapolis.

With the help of ancestry.com and other internet sources, Harrell has been able to update a lot of the family’s genealogy. There are some dates and names she hasn’t been able to find, and she tells her family if any of them know the information or where to find it to let her know.

The Siefker family would be eligible for the Bicentennial Award in 26 years, so do they expect Harrell to apply for it then?

“I told Grant, I said, ‘I don’t know. You’re talking 26 years from now. I’m 72 now. I’d be 98 years old.’ He said, ‘Well, you can do it then.’ I said, ‘Well, that depends on the good Lord,’” Harrell said, laughing. “Judy said, ‘Well, I’ll be 99. I don’t think I’ll be doing anything, either,’ so I told Grant, I said, ‘Well, it’s just going to have to be you. You’re going to have to update it and fill out the application.’”