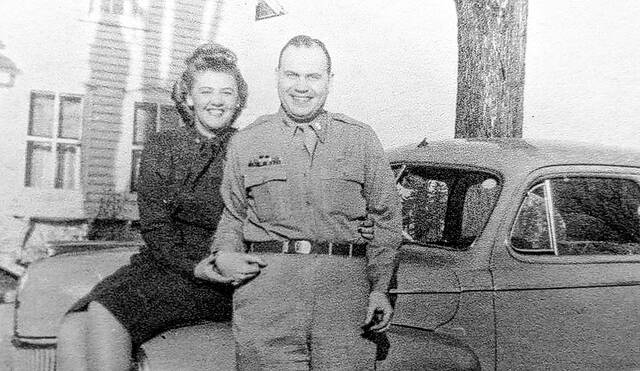

Seymour native Charles Beatty, right, met the woman who became his wife, Herta Gutzeit, while receiving treatment at an Iowa hospital for his fourth injury during World War II.

Submitted photo

From left, John Beatty, Richard Beatty and Bob Beatty are proud of their parents’ military service during World War II. Their father, Charles, was in the U.S. Army, and their mother, Herta, was in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps.

Submitted photo

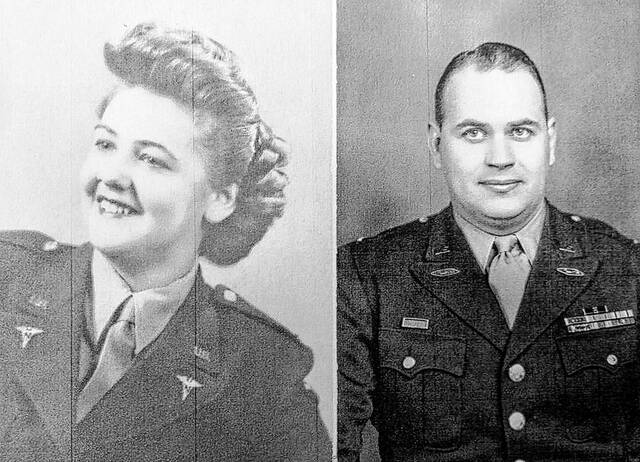

Herta Gutzeit, left, served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps and Charles Beatty was in the U.S. Army during World War II.

Submitted photo

Charles Beatty of Seymour served in the U.S. Army from April 23, 1941, to Oct. 10, 1947.

Submitted photo

Charles Beatty and Herta Gutzeit were married June 8, 1946.

Submitted photo

Herta and Charles Beatty were married for 61 years.

Submitted photo

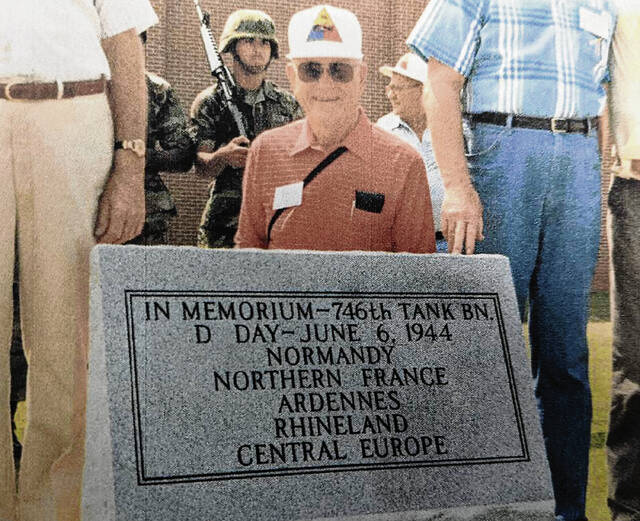

Charles Beatty visits the memorial for the 746th Tank Battalion at Fort Rucker in Alabama, where the battalion was first organized.

Submitted photo

After being wounded for the fourth time while serving in the U.S. Army during World War II, Seymour native Charles Beatty was shipped to Schick Orthopedic Hospital in Clinton, Iowa, for treatment.

He was wounded bad enough that it shattered the small bone in his leg, and doctors fused the two ends of the bone into the big bone of his leg and did numerous skin grafts.

Among those taking care of him was Herta Gutzeit, who was born in Germany and moved with her family to Iowa when she was 3. She was a registered nurse who had just been appointed as a second lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps and started working at the hospital.

Beatty spent a year at the hospital until it closed in March 1946, and he needed additional therapy, so he was transferred to Battle Creek, Michigan.

At Schick, he and Gutzeit had gotten to know each other because she became the head nurse on the ward, and they attended social functions together.

Their relationship blossomed, and she followed him to Battle Creek.

At one point on a leave, Charles and Herta got married June 8, 1946. That marriage wound up spanning 61 years. Charles died in 2007, and Herta died six years later.

They had three sons, Bob, John and Richard, who all still live in Seymour.

Bob said after his father died, he took his mom to Iowa for a family reunion. While there, they along with her sister, who also had been a nurse at Schick, and a cousin and her husband found the former hospital grounds. Herta and her sister pointed out where buildings once were and shared a memorable story about one of them.

“She started laughing, she says, ‘We had a dance at the officers club one night. I went by myself, and your dad came with another woman and left with me,’” Bob said, smiling. “I just treasure that.”

Each Veterans Day, Bob and his brothers and other family members take time to reflect on the contributions Charles and Herta gave to the country.

“Proud, first,” Bob said of how their service makes him feel.

“Proud and humbling,” John said.

Having other family members in the military over the years, Bob said he has always tried to put himself in their shoes to get a feel for what they experienced.

“That was the fascination for me with that whole period of history,” he said. “I soaked up ’40s as a kid, and still, every account I read, I try and put myself in what the times were then. It’s very difficult, but I try and figure out how all-encompassing that particular period of time was.”

On Veterans Day, Bob proudly shares pictures of his parents from their service time on Facebook. That post always receives multiple comments.

“(Charles) took a lot of pride in the military and the discipline, and we grew up with discipline,” John said, smiling. “He thought (the military) was good for him. He had a saying, he got this in the Army, ‘No excuses ever. No explanation unless I ask for it.’ We grew up with that: ‘I don’t care why you didn’t do this. You were supposed to do this. That’s the way it’s supposed to be.’”

Charles graduated from Shields High School in Seymour in 1936. He and good friend Joe Black then went to Indiana University at the same time, but Charles wound up with a bad case of poison ivy and wound up with an ear infection and had to come home.

“He had to spend all of his money for medical bills and couldn’t afford to go to college,” John said.

Charles later worked various jobs — the last being at a filling station in Seymour — until getting drafted for the Army in 1941. He was 23 at the time.

Not only did he receive a draft letter, but Charles received a second one letting him know he was appointed a group leader of his induction group to go to Fort Knox, Kentucky. He stayed there for eight weeks completing his basic training and then wound up with the 37th Armor Regiment at Pine Camp in New York in May 1941.

He remained in the United States until June 1944 when he landed on Utah Beach on what became known as D-Day with the Allied Forces in Normandy, France. He was a tank commander with the 746th Tank Battalion.

“One of the companies in his tank battalion went in on the initial assault. He was not. His company and platoon did not,” Bob said. “They went in about 1 o’clock, 1:30 in the morning on June 7.”

The infantry commander general at the time was Teddy Roosevelt Jr., the eldest son of the 26th U.S. president, Teddy Roosevelt.

“They were 1,500 or 2,000 yards from where they were supposed to be when they landed, and (Roosevelt) was the one that said, ‘Well, I guess we start the war from right here,’ and he said, ‘Let’s go,’” Bob said. “Then they headed inland and were having to fight through those coastal defenses. Dad came in at 1:30 in the morning. He told me one time, he said, ‘We just drove off the ship and headed inland, grouped up and waited for orders.’”

Four days later, Charles was wounded for the first time when the tank he was in came under fire from the Germans at a crossroads, resulting in the driver being killed instantly. Then June 25, he was injured again.

“The first incident was one I got him to relate to me one time,” Bob said. “He was very reluctant to do that, like most are. Most guys that really saw significant battle are reluctant to talk about it, and Mom said, ‘If I ever got him to do that, to open up about it, he would have trouble sleeping for a few nights.’”

Back at the company command post, Charles reported what he saw to Roosevelt. As Charles was dismissed, Roosevelt noticed his .45-caliber pistol was gone. Charles had lost it while coming out of the tank.

Roosevelt then handed him his pearl-handled Colt Commander and told him he needed it more than him.

“He had that for a while until he got wounded in August and got sent back to England,” Bob said. “They shot them full of morphine when they were severely wounded, and the medics would steal everything you have. That’s when one of the medics saw that gun and said, ‘I’ll have that.’ It breaks my heart that I don’t have that.”

That’s one story Bob got his father to relay about combat.

Another story was when Charles was awarded a Bronze Star for Gallantry for leading his platoon out of a mine field. He stepped on an S-mine, which American infantrymen referred to as “Bouncing Betty,” and fortunately, it didn’t go off.

“Slave labor in the German concentration camps were putting all of that stuff together, and a lot of them just put it together so it would misfire,” Bob said. “I often wonder if that’s what the case was.”

Charles received his fourth Purple Heart after being wounded for the fourth and final time and later was separated from the service Oct. 10, 1947, as a captain.

While many people over the years told Charles he was a hero, Bob said he was the first to deny that and say the heroes were still fighting for their country.

He didn’t talk too much about his service in the war and didn’t like watching war movies. He, however, instilled in his sons an interest in history.

“I was into history, and I wanted to know about it. I was fascinated by it,” Bob said. “At one time as a kid, I thought I would like to be in the military.”

After leaving the Army, Charles’ injuries prevented him from doing manual labor and being on his feet all day.

He held a few different jobs until his insurance career began in 1954 with Hobbs Miller Insurance Inc. in downtown Seymour. He remained in that field until retiring in 1981.

Herta remained a registered nurse until they started a family. Then she stayed home to take care of her three boys. Bob said his mother still renewed her Iowa board of nursing license each year and helped with blood drives and other things as she could.

When Charles retired, he and Herta moved to Florida for the winters, and that’s how he became reacquainted with his old company commander and a couple of his Army buddies.

“That was good for him,” John said. “They became best friends again immediately, and they resurrected their Army reunions. That was good because he could talk to them about it because they knew, they understood, they were there.”

Along with the Purple Hearts and Bronze Star for Gallantry, Charles earned several citations: European-African Middle Eastern Theater Ribbon with four bronze service stars, Bronze Arrowhead for the D-Day invasion, World War II Victory Medal, American Theater Ribbon and Croix de Guerre with a silver star from the French government.