If ever there was a motto that summed up the encouragement offered to developmentally disabled children by the Seymour school district — and is the cornerstone of Elizabeth Schlatterer’s career philosophy — it is spelled out on a sign on the wall in her Margaret R. Brown Elementary School classroom.

“Never forget how fabulous you are,” proclaims the message shared by the teachers in the special education room.

Schlatterer hopes that means something to the young people she has tutored for nearly a half-century.

Schlatterer, soon to turn 70, has been a special education teacher in Seymour for 48 years since beginning right out of college at Indiana State University in 1973.

But she is retiring at the end of this school year.

Schlatterer is the longest-serving Seymour teacher taking retirement in 2021 after being the first special education teacher hired by the district when American society was first coming to grips with how to better serve children who had been dealt a tough hand.

It was not long before that it was typical to warehouse many children in institutions or otherwise overlooking them.

“I have seen such tremendous growth in the special education department,” Schlatterer said. “It’s very different.”

The approach to challenged children now is inclusion, and even the terminology is more polite in terms of how individuals are viewed and treated, she said.

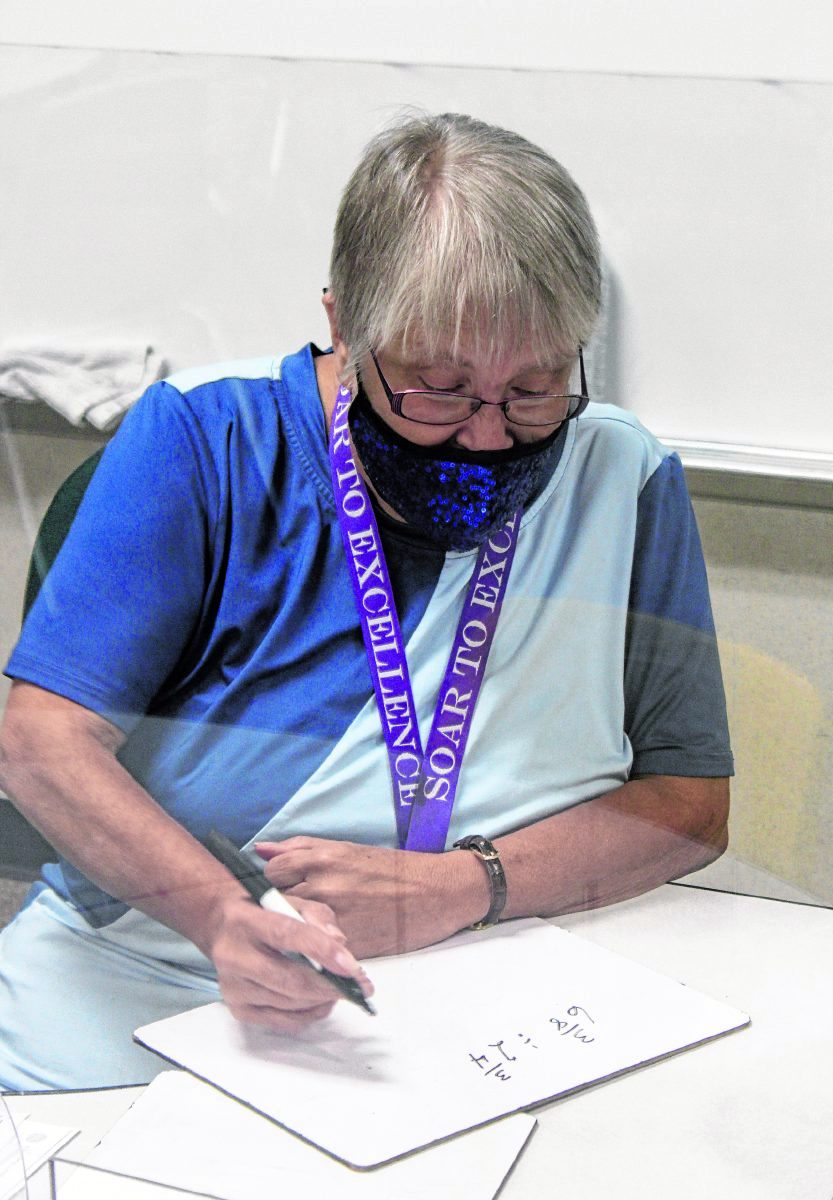

As the end of her school day approached, Schlatterer was gently instructing two boys in the finer points of arithmetic problems while two other groups met with other instructors at small tables.

“Most of the time, the kids are spending most of the day in the classroom in general education,” Schlatterer said.

Sometimes, the students are pulled out for extra attention in math or reading.

“We try to push them forward,” she said.

Schlatterer grew up in Seymour, attended Seymour schools and earned undergraduate and graduate degrees at Indiana State. She thought she would be a mainstream elementary school teacher.

“I knew I wanted to do something with kids,” she said.

When Schlatterer completed college, however, there were not many public school openings. When she was offered an interview back home, she thought it would be just for practice. She was surprised on two fronts — a job was offered and it was to teach special education. Until that moment, at 22, she had never thought it would become her specialty.

“It was a shock to me,” Schlatterer said.

Communities and schools were starting to realize they had a constituency that wasn’t being taught, and parents were demanding more for their children. The Education for All Handicapped Children Act was passed by Congress, providing a legal right to education for children with disabilities.

Schlatterer has been in the middle of special education advancing from minimum requirements through five decades of improvements.

“Compared to what special education is now,” she said, “it was a one-room schoolhouse.”

In her early days of teaching — and before that — if a family had a special needs child, it was pretty much its own responsibility to take care of him or her.

“They were cared for and protected by their families,” Schlatterer said. “There were no expectations, and when you have no expectations, you get nothing.”

The world is a better place for those with special needs with many things contributing to the change, she said, notably Special Olympics. Schlatterer coached athletes in that realm for 30 years, too, though she stopped when she adopted a boy and began following his athletic career. Though not before once being named Indiana Special Olympics coach of the year.

Brown Elementary Principal Tony Hack, who has worked with Schlatterer for 10 years, said modern special education instruction is indeed improved. Schlatterer has seen it all, and Hack said there is one distinct way the overall attitude difference can be explained.

Special education now, he said, is taught with “the ability to have students that have differences be celebrated instead of isolated. We’ve had more and more opportunities to bring them a well-rounded education and be more inclusive.”

With Schlatterer, a pioneer of special education in Seymour departing, Hack said he is tasked in figuring out how to continue moving forward.

“The thing that goes through my mind as a principal is, ‘How are you going to replace her?’” Hack said. “How do you replace that experience? How do you maintain that level of success? How do I take it from here?”

Schlatterer said friends and family members wonder how she took on and stuck with teaching special education for so long. They assume she was gifted with an extraordinary amount of patience, but she doesn’t believe that frequently repeated word to her is accurate.

“You don’t have to be patient,” Schlatterer said. “You’ve got to be understanding and kind at the right time and place.”

When Schlatterer accepted the job, spending her first three years at Redding Elementary and ever since at Brown, she was told, “You will learn more about behavior than you will anywhere else in your teaching career.”

That has been true. One girl, she said, 7 or 8 years old, because of an affliction “couldn’t hold her head up.” Another youngster, about 8 or 9, could not talk at all, and if she wanted something, she pinched Schlatterer’s arm in a twist. “Bless her heart.” That girl led a mini-rebellion once, breaking into the cabinet where Schletterer kept her lunch, and distributed the food to the students.

Sometimes, Schlatterer thought, “Who’s the one here with the challenge, them or me?”

One boy was a constant troublemaker, and she took him out in the hall and mixed a lecture with praise, telling him if he applied himself, he could obtain a diploma and do things in life. She also offered a compliment about his brown eyes. She told him when he graduated from high school to send her an invitation. The message seemed to take, but the boy moved away.

“Six years later,” Schlatterer said, “I got an invitation to his high school graduation from Kentucky.” She went to the event, too.

There have been everyday teaching triumphs that stick in her mind, too, the joys any teacher experiences in a classroom, though perhaps more so because her students may have come farther.

“That happens when you have a kid that learns,” she said. “All of a sudden, it’s ‘I’ve got it.’ You never know. The smallest thing you do, it becomes a big deal.”

Schlatterer’s last day is June 1. She is leaving now, even though it seems as if the time went by quickly, because she is feeling a bit older and wants to spend some time traveling. Her son is getting married in August, too, so that special event is on the horizon.

She is beginning to feel more emotional about her pending retirement as each day passes and said she can’t imagine how she will cope on her final day of work.

“I’m going to be such a mess by June 1,” Schlatterer said. “I’ll be pathetic.”

Schlatterer hopes her legacy will live on in the kids she instructed over 48 years, way back when and now, and hopes that every child who enters the special education classroom absorbs the memo about being fabulous.

“I want it to mean to the kids, ‘You can do it because you set your mind to it,’” Schlatterer said.

[sc:pullout-title pullout-title=”At a glance” ][sc:pullout-text-begin]

Seymour Community School Corp. 2021 retirees

Rosemary Albright, 13 years, elementary teacher

Dennis Banks, 10 years, custodian

Janet Duggins, 12 years, administrative assistant

Jack Hauer, 7 years, school resource officer

Lou Ann Hoevener, 26 years, bus driver

Gayla Kaiser, 36 years, special education teacher

Tom Lucas, 34 years, math teacher

Kim Mellencamp, 22 years, custodian

Ellen Mirer, 38 years, band director

Paul Newlin, 27 years, special education instructional assistant

Dawn Otte, 22 years, ECA treasurer

Jonathan Otte, 29 years, vehicle maintenance technician

Denny Plumer, 31 years, head custodian

Shirley Roberson, 2 years, special education instructional assistant

Terry Schryer, 21 years, bus driver

Elizabeth Schlatterer, 48 years, special education teacher

Tom Snyder, 47 years, bus driver

Deborah Sons, 30 years, assistant kitchen manager

Keith Stam, 38 years, choir director

Rodney Tatlock, 4 years, custodian

Kathy Thurston, 41 years, teacher

Robin Tormoehlen, 15 years, elementary teacher

Denise Wright, 18 years, instructional assistant

[sc:pullout-text-end]