They will always be the true Hoosiers, the ones who personified Indiana’s state sport, the ones who created the miracle, the ones who gave underdogs hope.

The players may not live forever, but their achievement will.

The calendar stopped March 20, 1954, for the Ripley County town 48 miles from Seymour with a game that has been immortalized by everyday basketball-playing high school boys and one of the greatest sports movies of all time.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]

We are reminded of this singular and feel-good accomplishment again with the late June death of Glen Butte at 81, one of the authors of “The Milan Miracle.”

Yes, the calendar froze, but the clock did not. The Milan boys have aged into senior citizens, and one by one, their time is passing.

There was a purity and an innocence to high school sports 66 years ago. It was a hard road to win a state championship. Unlike today, in Indiana and all over the United States, organizations that supervise high school sports have divvied up the big schools and the small schools, separating them into categories like Class 5A and Class A.

That was supposedly done in the interest of fairness, giving even the smallest of the small a chance to win a championship. So instead of one champion, we have five at a time. The change took hold over decades, and now, hardly anyone thinks about how it used to be.

In 1954, the tournament was as much about David vs. Goliath in any given game, and we all know from Sunday school that sometimes, with strategic planning, good coaching and the stoutest heart that sometimes the slam-dunk winner does not always win. Everyone can be beaten.

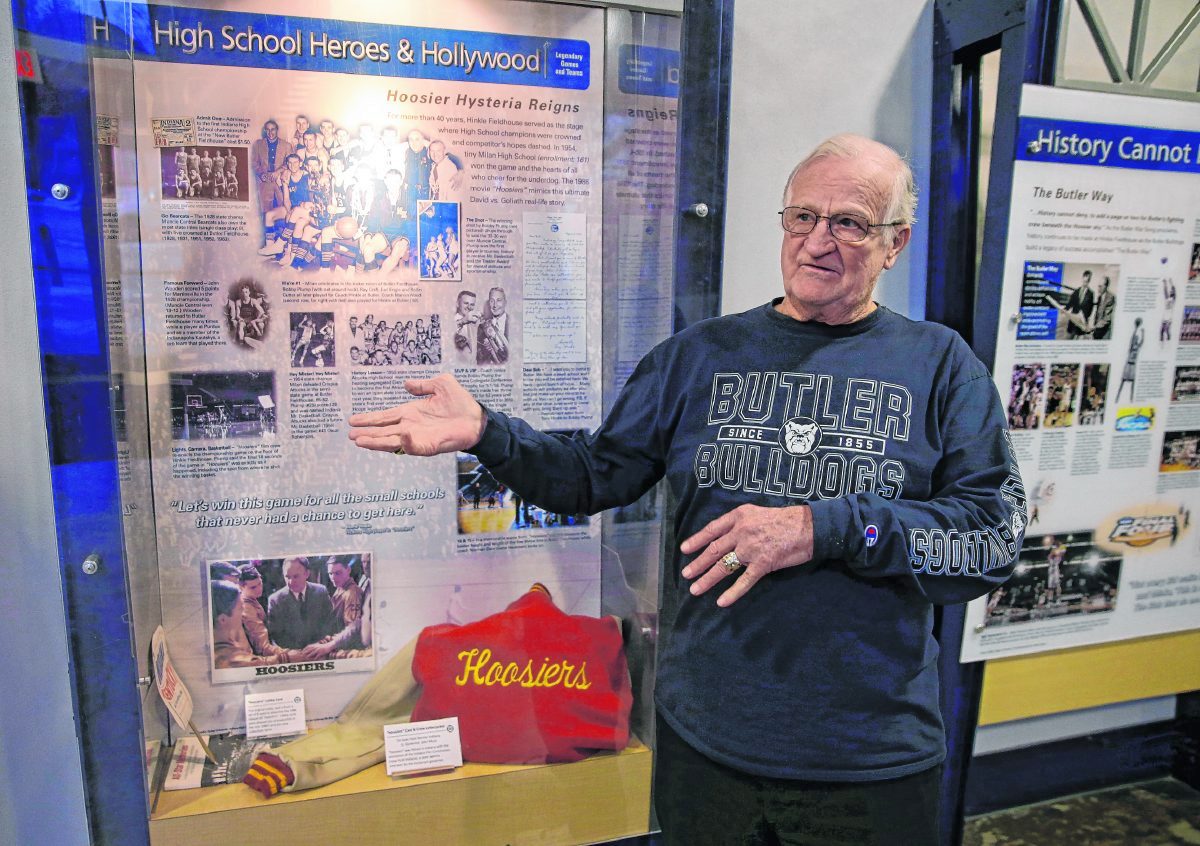

So it was with Milan against Muncie Central. Milan coach Marvin Wood and his players may have been the only humans among the 15,000 jammed into Butler’s Hinkle Fieldhouse who believed.

Milan’s student body was 161, which means there were more boys in the school than the 1986 film implied, though fictional liberties can be expected even in a true story out of Hollywood. Research indicates there were 73 boys enrolled and 58 of them tried out for the team. “Hoosiers” stayed close enough to verities that no one has ever quibbled with its job burnishing the legend.

The film portrayed Milan as a group of hicks who seemed awed by their trip to the big city of Indianapolis. Certainly, Milan did not play home games or routine road games in arenas as large as Hinkle.

There is a scene when the team arrives for its big game when the coach, played by Gene Hackman, has the boys measure the height of the hoop. The point is that the building may be big, but the dimensions of the floor are the same as they are everywhere.

Not emphasized is that Milan had advanced in the 1953 state tournament and played Hinkle already, so the Indians were not nervous about that. In a conversation nine years ago, Butte said, “We’d been there in 1953. We didn’t look up and measure the goal.”

“Hoosiers” is a movie and a stirring one, but as Butte and star guard Bobby Plump noted in real life, the players were not as wide-eyed as was indicated.

“Most people are surprised that we didn’t come out of nowhere,” Plump said. “That’s what people forget.”

Road to Hinkle

Even on the journey to that state crown, those guys bested Crispus Attacks with Oscar Robertson, too. Robertson was just a sophomore, but he was on his way to becoming one of the greatest basketball players who ever lived.

A pilgrimage to Milan High School for a game in the old gym about nine years ago revealed one of the most marvelous of commemorative items a team could ever preserve. In one corner was a small scoreboard, and the score of 32 Milan, 30 opponent was permanently lighted. That was the final score versus Muncie Central.

Milan did a worthy job preserving history. Winning that game was an electrifying moment, and anyone who loves sports, basketball and Indiana basketball appreciates it. What was unclear at the time, for the players, for the community, for the state tournament and all Indiana basketball fans, was how well the victory would be recalled.

It is easy to look back now and recognize the significance, yet in the heat of the celebration and in the immediate aftermath, not even those directly involved were sure what winning it all would mean down the road.

After all, there was another state championship game to be played the next year, in 1955, and the next, and every year after.

But the Milan guys underrated themselves. In 1955, players got together for a one-year reunion and Ray Engel asked, “Do you think people are going to remember this next year?”

In the early 1950s, none of the technology that rules the lives of today’s teenagers was in operation. Several of them got together regularly to play ball, Butte, Plump, Roger Schroeder and Gene White, and they called themselves the Pierceville Alleycats. When Plump received a basketball and hoop one Christmas, they are shared in the spoils.

“There really wasn’t much to do, and we played in all kinds of weather,” Butte said, remembering none of them had access to a television set then.

They played long hours, they played hard and they honed their games. The Indians had no shortage of confidence for 1954.

“We never went on a basketball court where we didn’t think we could win,” Plump said.

Completing the regular season, Milan was 19-2. By the time they cut down the Hinkle nets, the Indians were 28-2.

The shot

The real game and the movie played out similarly. With 6 minutes remaining in regulation, Muncie Central led 30-28. These were the days before the existence of a shot clock (the first one was just being introduced in the NBA) and Wood told point guard Plump to shorten the game.

The 6-foot-1 Plump stopped at midcourt, put the ball on his hip and stood there, wasting about 4 minutes. When Milan charged the hoop, Plump missed a layup, but teammate Ray Craft was fouled and hit two free throws. 30-30 with 18 seconds left.

Milan got the ball back and cleared out for Plump to take the last shot. He was going to make the shot for glory or the game would go into overtime. Plump dribbled, slashed between defenders and stopped to take a medium-range jump shot with 5 seconds left.

He made the perfect shot. It was an improbable finish, just like in the movies. Yes, Milan celebrated like there was no tomorrow, and the Indians, the basketball team and the townspeople have never stopped celebrating through decades of tomorrows.

The Indians got to live the joyous ride all over again when “Hoosiers” was released to great acclaim and when publications such as Sports Illustrated and large Indiana newspapers proclaimed The Milan Miracle one of the greatest sporting accomplishments of the 20th century.

Plump, who was Indiana’s Mr. Basketball, graduated right onto Butler’s roster. Craft played for the Bulldogs, too. Butte played for Indiana University and legendary coach Branch McCracken. Others played for nearby Franklin College. Ronnie Truitt played for the University of Houston.

Basketball didn’t end for them there, nor did the Milan connection. They represented a place and a time revered in community history, and their unlikely shared journey cemented their ties.

“There is still that special bond,” Plump said, long after they were all out of school, raised families and lived full lifetimes.

In 2010, the closest thing to an Indiana replay occurred. Against the odds, Butler University, considered a mere mid-major program at the time, almost pulled off a Milan. Butler qualified for the NCAA Final Four, which was being played in Indianapolis a few miles from campus.

The more Butler won during the early rounds of the tournament, the louder the comparisons got. After Butler won its semifinal game and earned the right to play Duke for the title, Bulldogs star Gordon Haywood spied a local sportswriter he knew and told him a light-hearted story.

Just the night before, flicking the TV channels in his hotel room, Haywood said, the clicker paused on “Hoosiers” being shown. He laughed. The NCAA title game came down to Haywood taking a 30-foot heave that bounced off the rim. This time, Muncie Central, aka Duke, won it all, and the underdogs, as more often happens, were doomed to a cycle of what if.

Not Milan, though. The Indians were feted after hustling to glory. The town saved everything that pertained to the championship, newspaper clippings and souvenirs, 57 boxes of materials.

“You were one of the town heroes,” Butte said.

Now, one by one, Butte and the others, teenagers become grownups, become senior citizens, symbols of a distant era, are dying off.

The men may not live forever, but what they did will.