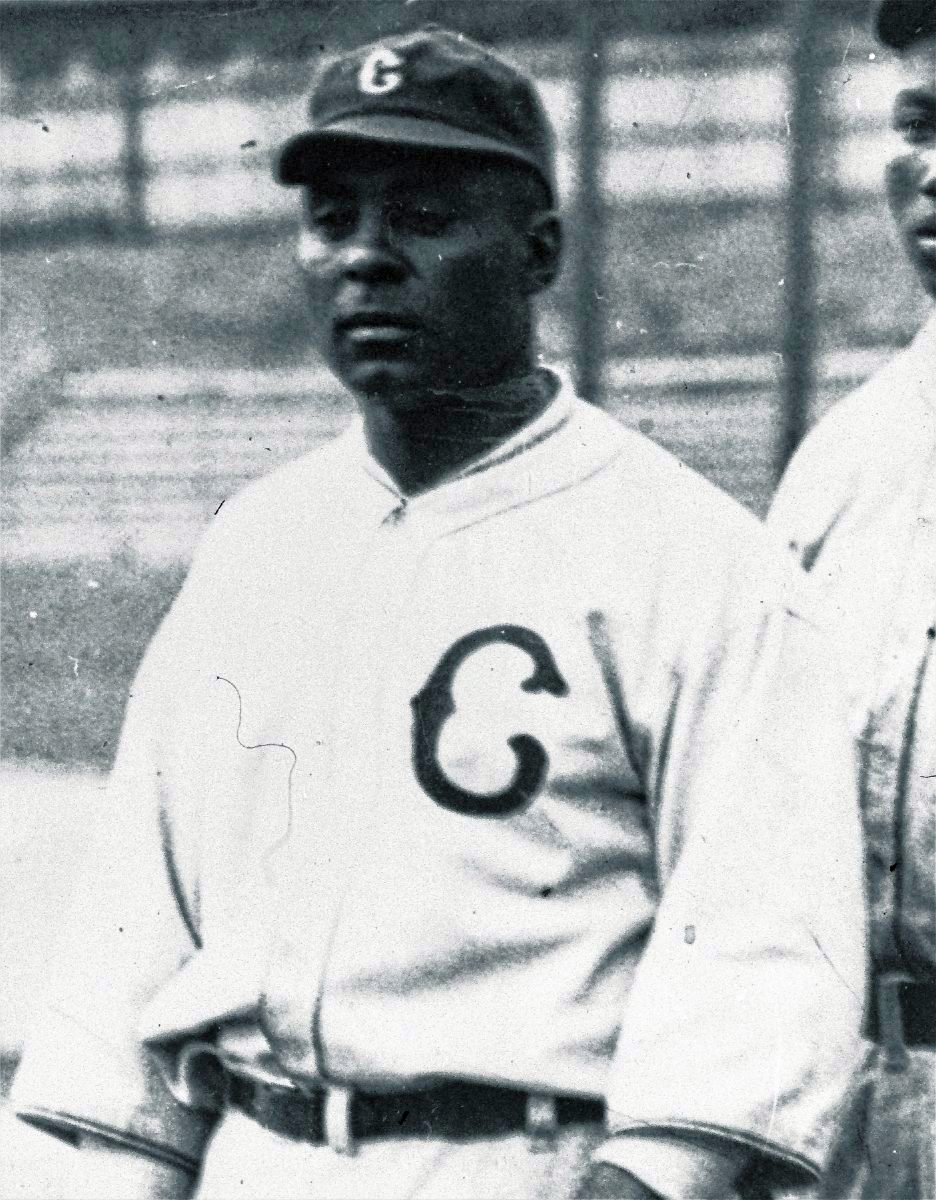

Oscar Charleston was as much Hoosier as the basketball movie.

Charleston was born in Indianapolis in 1896, grew up in the Indiana Avenue neighborhood, attended school in the city, was a batboy and then a star for the Indianapolis ABCs beginning in 1915 and managed the Indianapolis Clowns at the distant end of his career and life in the 1950s.

The Negro Leagues player most revered by old-timers, Charleston was gazelle-like enough with his catches in center field to make fans gasp and murderous enough at the plate that the thwacking sound of his bat colliding with ball was as clear as a signature.

He was an aristocrat of the diamond who led by action and demeanor, even when his temper erupted protesting the feel of being cheated by umpires. To see him at his finest provoked adoration from spectators and players sufficiently discerning to identify greatness.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]

“Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth and Tris Speaker rolled into one,” said the Kansas City Monarchs’ Buck O’Neil of Charleston’s prowess.

He stood shy of 6 feet tall and weighed about 190 pounds, and Charleston possessed inordinate strength. For all of that, Charleston was past his prime when he made cameo appearances for two exhibition games in Seymour in May and June 1940.

The first game was announced this way in the Seymour Tribune of May 22: “Colored Team Will Play Reds Sunday.” Advanced scouting suggested, “It is reputed to be one of the fastest colored teams ever to be assembled in Indianapolis.” Fastest, as in best.

That season, a year shy of retirement as an active player, Charleston appeared at old Redland Field at Eighth and Blish streets against the local Seymour Reds club. The Tribune of 80 years ago reported a 5-3 victory for the Indianapolis ABCs with Charleston in center collecting one hit. About a month later, the Reds drubbed the ABCs 10-3. Charleston went 2-for-3, scored two runs and hit a homer.

The newspaper called the visitors the ABCs, but career affiliations list Charleston playing for the Indianapolis Crawfords that year. If Babe Ruth had come to town, local baseball fans would still talk about it. Oscar Charleston was nearly the equivalent.

The original ABCs, founded in 1897, were named for the American Brewing Company. There had been several high-level Indianapolis white teams in the early days of the National League (the Indianapolis Blues in 1878) and in the American Association in the 1880s when that was a major league.

Briefly, in 1913-14, the Federal League was considered major league and the Indianapolis Hoosiers were a local franchise.

The ABCs home field was Northwestern Avenue Ballpark until 1916 when it was torn down and replaced with freight yards. The team then shifted its games to Federal League Park, where the Hoosiers competed before becoming the Newark Peppers.

For a a few decades of the 20th century, the best baseball in Indianapolis was played in the Negro Leagues. The ABCs appeared in the first Negro National League game in 1920 and remained in the league until 1926.

The so-called “colored teams” of the time played league games, exhibitions games against white semi-pro teams, toured by bus.

To Charleston’s peers, it was not a matter of whether he could have competed in the big leagues if not for racial prejudice but just how colossal of an impact he might have made.

The insult added to the injury of segregation was the unreliable statistics kept as black players barnstormed. There have been heroic efforts made in recent years by researchers to piece together box scores and individual numbers for Negro Leagues players.

Charleston was credited with batting .339 lifetime in Negro Leagues games and .326 in games against white competition. It was harder to hit a ball over Charleston’s head than it was for others to catch up with his clouts.

“He could go back on a ball, and it looked like the ball would wait until he would catch up with it,” said Judy Johnson, a Negro Leagues third baseman in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The Clowns

More famous in memory than many earlier Negro League teams were the Indianapolis Clowns. The Clowns even barnstormed after the Negro American League folded.

Formed as the Ethiopian Clowns in Miami in the 1930s for comedy, they morphed into a serious team with show business mixed in. The Clowns moved to Cincinnati in 1943 and two years later to Indianapolis.

Good enough to win their league championship in 1950, the Clowns were also promoted as the Harlem Globetrotters of hardball and called “entertainers.”

Much as the Globetrotters do while traveling around the world, the Clowns played shadowball, mimicking throwing and catching of baseballs in a dazzling theatrical display.

Pitcher Ed Hamman introduced shadowball to the team and also threw fastballs between his legs while sometimes adjourning to the stands to sell peanuts and game programs.

Reece “Goose” Tatum, one of the Globetrotters, was one of the Clowns. Tatum sat in a rocking chair while he tried to cover second base and employed hidden ball tricks.

The team employed comedians who did not play. Spec Bebop was a dwarf who performed vaudeville routines. Richard “King Tut” King wielded a gigantic catcher’s mitt and was seen dancing in a grass hula skirt. King Tut was affiliated with the Clowns for 20 years. His record shows only seven at-bats. His specialty was making people laugh, not stroking base hits.

“Prince” Joe Henry played most of his prime in black ball, then got a chance in the white minors with the Memphis Red Sox in his 30s. After being injured, he joined the Clowns in their waning days.

Henry’s wore a tuxedo and top hat to take his cuts. He showed off red shoes and at the plate could turn his back on the pitcher, then abruptly spin toward the mound and drive the ball.

Despite his delayed call to the minors, baseball integration was essentially too late for Henry, who died at 78 in 2009. But he cherished his baseball memories.

“The Negro Leagues took me to just about every state in the country and Canada,” Henry said.

As fan support declined and Negro Leagues teams were failing, Clowns owner Syd Pollock, a promoter by nature, in 1953 signed Toni Stone, the first woman to play in the Negro Leagues, and followed with Mamie Johnson and Connie Morgan. No woman has ever played in the white major leagues.

Hank Aaron was hired for his talent, not his sense of humor.

While in high school, Aaron, born in 1934 in Mobile, Alabama, played for the Pritchett Athletics for $2 a game, then the independent Mobile Black Bears for a $1 raise. He was 17 in late 1951 when the Indianapolis Clowns signed him.

Aaron’s mother, Estella, wanted him to stay home, but he left for Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to meet the Clowns, traveling by train while carrying two homemade sandwiches and $2 in his pocket.

The young player said he was a nervous wreck, wondering if he was good enough. He weighed just 150 pounds, and veterans hazed him with rookie abuse. The Clowns made fun of his worn-out shoes and he wrote in his autobiography, “They asked me if I got my glove from The Salvation Army.”

Aaron described himself as shy and not worldly and was “an easy target.” The teasing ceased when he took his turns batting.

After turning 18, Aaron played three months of shortstop for the Clowns at $200 a month. He was afforded the opportunity Charleston and so many other Negro League legends did not receive. By then, most big-league teams were aggressively scouting young black talent.

Aaron was tendered offers by the New York Giants and the Braves, who were just forsaking Boston for Milwaukee. Aaron said the Braves deal was for $50 more, otherwise he would have shared the same outfield as Willie Mays. By June, Aaron had departed the Clowns.

Years later, Aaron recalled the discrimination the team faced on the road.

“We almost never stopped in a restaurant because it was hard to find one that would serve us,” Aaron said. “Sometimes, we’d be on the road for a week before we got a chance to wash our clothes.”

A scarring incident Aaron carried with him from his stay with the Clowns revolved around a team breakfast the Clowns ate in Washington, D.C, when after finishing the meal the players heard plates being smashed in the kitchen.

“What a horrible sound,” Aaron recounted. “Here we were in the capital of the land of freedom and equality, and they had to destroy the plates that had touched the forks that had been in the mouths of black men. If dogs had eaten off those plates, they would have washed them.”

Oscar in decline

When salaries were much lower and there were no televised games, even the best players in the majors sought extra cash and exposure in parts of the United States where only their names, not their games, were known.

St. Louis Cardinals hurler Dizzy Dean was one of the leaders in this realm, often putting together post-World Series tours. Dean may have been a son of Arkansas but had no qualms playing against top black ballplayers, and he said Charleston was something to see.

“He used to play against us in exhibition games,” Dean said. “He could hit the ball a mile. He didn’t have a weakness, and when he came up, we just hoped he wouldn’t get a hold of one.”

As a young man, even when he could inspire such awe in games, Charleston was not above a little clowning on the field.

With the Homestead Grays, he engaged in shadowball warmups and sometimes did acrobatic showoff stunts after making a catch. In homage to his Indiana roots, Charleston was billed as “The Flying Hoosier.”

When Jackie Robinson defied segregation with the Dodgers in 1947, Charleston knew it was too late for him. He was already well into a managing career.

“I never got a chance to play in the majors because of the color line,” he said. Now, he was working hard “to see that that these kids I’m managing get their chance.”

In 1951, an Oscar Charleston Night was ballyhooed at Victory Field in Indianapolis. Then the Clowns brought him back to Indianapolis as manager for 1954. He was overweight and his skills had deteriorated, but once in a while, when the mood struck him, he inserted himself into games as a pinch hitter. His team won the Negro American League title.

Even though Charleston felt unhealthy for much of the season, he re-upped for 1955. Soon after, though, Charleston took a devastating fall on a staircase and was diagnosed with cancer. In October 1954, he died at 57.

Charleston was buried in Floral Park Cemetery in Indianapolis with only a basic military grave marker as an identifying stone that was based on his teenage Army days.

Before the coronavirus closed so much of America this spring, Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, planned a commemorative occasion noting the Negro National League’s May 2, 1920, first game in Indianapolis.

As part of Kendrick’s journey to Indiana, a ceremony was scheduled to place an enhanced headstone on Oscar Charleston’s grave. Placement of the headstone was accomplished with less fanfare than it deserved.

In that way, it paralleled Charleston’s baseball career.