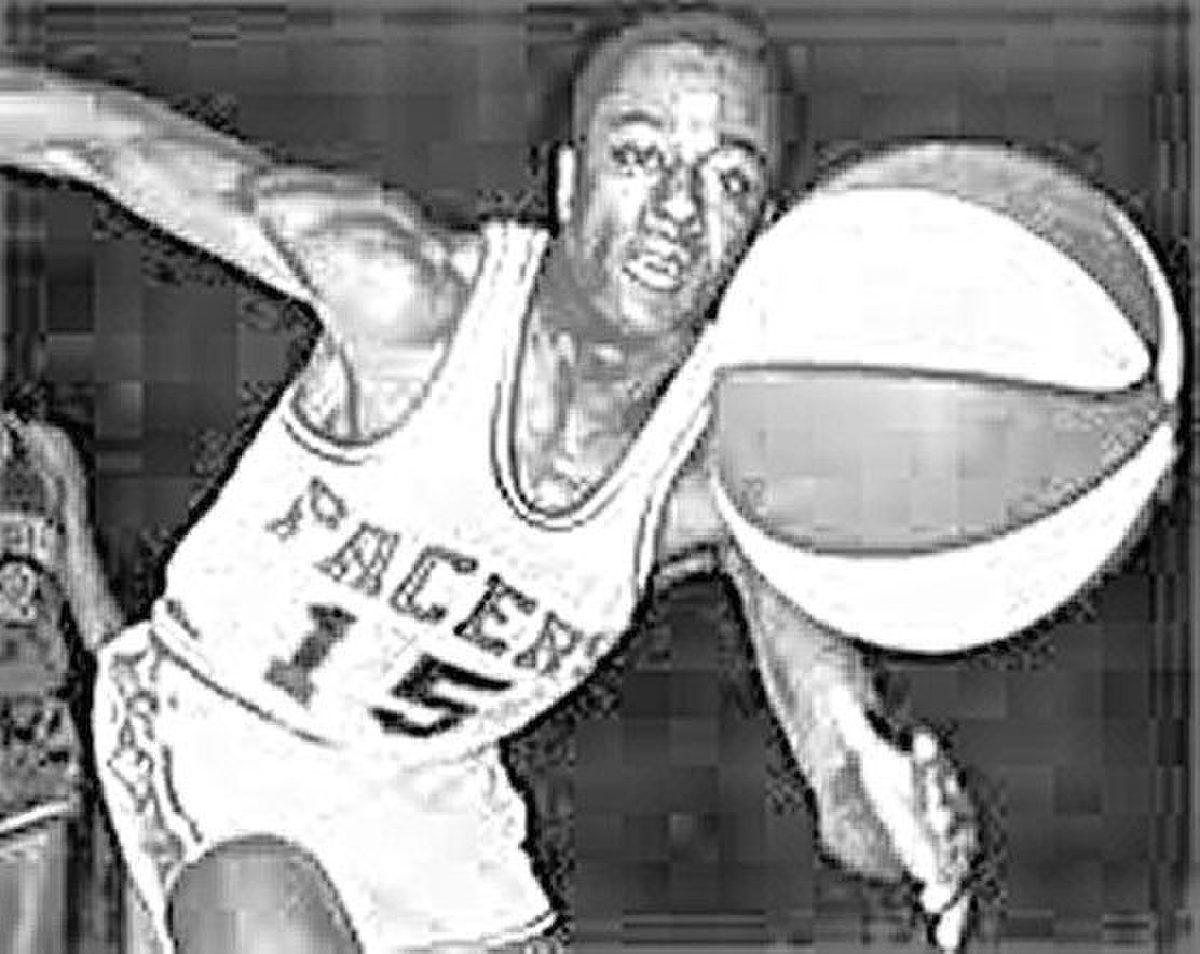

As an illustration of how long ago original Pacer Jerry Harkness’ miraculous shot from 1967 was, there is no video.

Far from every move in the American Basketball Association was well-documented as the fledgling league fought for survival against the established National Basketball Association.

On Nov. 13 of that year, the Indiana Pacers’ first season, Harkness flung a shot 92 feet as the clock ran out for the ultimate ABA buzzer beater. It was the longest shot recorded in league and team history. The heave — and there is no other way to describe it — defeated the Dallas Chaparrals 119-118.

Only trivia experts recall the Chaparrals were forerunners of the San Antonio Spurs.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]Click here to purchase photos from this gallery

Eyewitnesses to Harkness’ game-winner were scarce. This is going on 53 years ago, but Harkness, 79, who still lives in Indianapolis and makes appearances for the Pacers, said the odd play comes up “a lot. It really does.”

He finds this humorous, Harkness said recently, because it is an arcane record and because Pacers fans often tell him they were present at the Coliseum when he hit this long-bomb touchdown-type throw. The game was not on TV, Harkness said, and he actually made the shot in Texas, not Indianapolis, with the attendance skimpy that night.

“Most of the people think it happened at the Coliseum,” Harkness said. “They say, ‘I was right there at the Coliseum.’”

He no longer corrects them.

“I just let it go,” he said.

Harkness believes his record-length shot was broken by Charlotte Hornets guard Baron Davis in 2001, but it is apparently not true. One source indicates Davis made an 89-foot shot with less than a second remaining in a third period against the Milwaukee Bucks. Another credits Davis with a 92-foot shot.

When Harkness was growing up in New York City, opportunities for African Americans to obtain college basketball scholarships were limited. A combination of good fortune and fate led him to Loyola of Chicago and an NCAA title.

The 1963 Ramblers, a team that faced considerable discrimination because coach George Ireland routinely started four black players and fielded several others, were booed and insulted in Houston and New Orleans.

The team formed a special bond, a unifying squad in a time of major social unrest in the United States, whites and blacks not only sharing the ball, but a legendary underdog overtime title triumph over the University of Cincinnati. Harkness was the captain and a first-team All-American.

Loyola endured death threats as well as basketball threats from the best teams in the country, emerging triumphant in more than one way. During the NCAA tournament, Mississippi State’s all-white team defied state rules to escape campus to play Loyola’s mixed-race team. So much significance was paid to this simple contest it was memorialized as “The Game of Change.”

It took decades for the Ramblers to receive their due as pioneers. In 2013, surviving team members met with President Barack Obama at the White House.

For a time, the harshness of the racism faced made Harkness wonder how important Loyola’s accomplishment was. But the experience transformed him into a civil rights activist. He has been repeatedly honored for efforts as executive director of the Indianapolis chapter of 100 Black Men and work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the 1970s after retiring from basketball.

Harkness, a 6-foot-3 undersized forward, also played for the New York Knicks, but his allegiances to Loyola and the Pacers are strongest.

Not all members of the team lived long enough to be recognized by the president and just last Friday, star forward Les Hunter passed away from cancer, a sad moment for Harkness. Several of the players got together annually, and Harkness fondly recalled sharing a recent race track visit with Hunter enjoying the ponies.

Harkness has witnessed up close more easing of racial intolerance than just in basketball. Rambler players became friendly with Mississippi players. When he was in school, Harkness said, the black players could not even comfortably enter white guard Jack Egan’s Chicago neighborhood. Not long ago, they spent the night.

“That’s beautiful,” Harkness said. “It’s like night and day.”

In late February, Harkness and former Pacer Darnell Hillman represented the team in Kokomo when the city honored another ex-teammate in Jimmy Rayl. Rayl died at 77 in January 2019, and the community where he starred in high school basketball named a street Jimmy Rayl Boulevard in front of the gym.

Harkness says he regularly attends Pacers games as a guest of the team, and he does autograph signings for the club.

Harkness, who recently authored a book about his life called “Connections,” definitely remains very connected to the Pacers so many years later.