Blake Everhart, foreground, racing in a recent hydroplane event in Hillsdale, Michigan.

Submitted photo

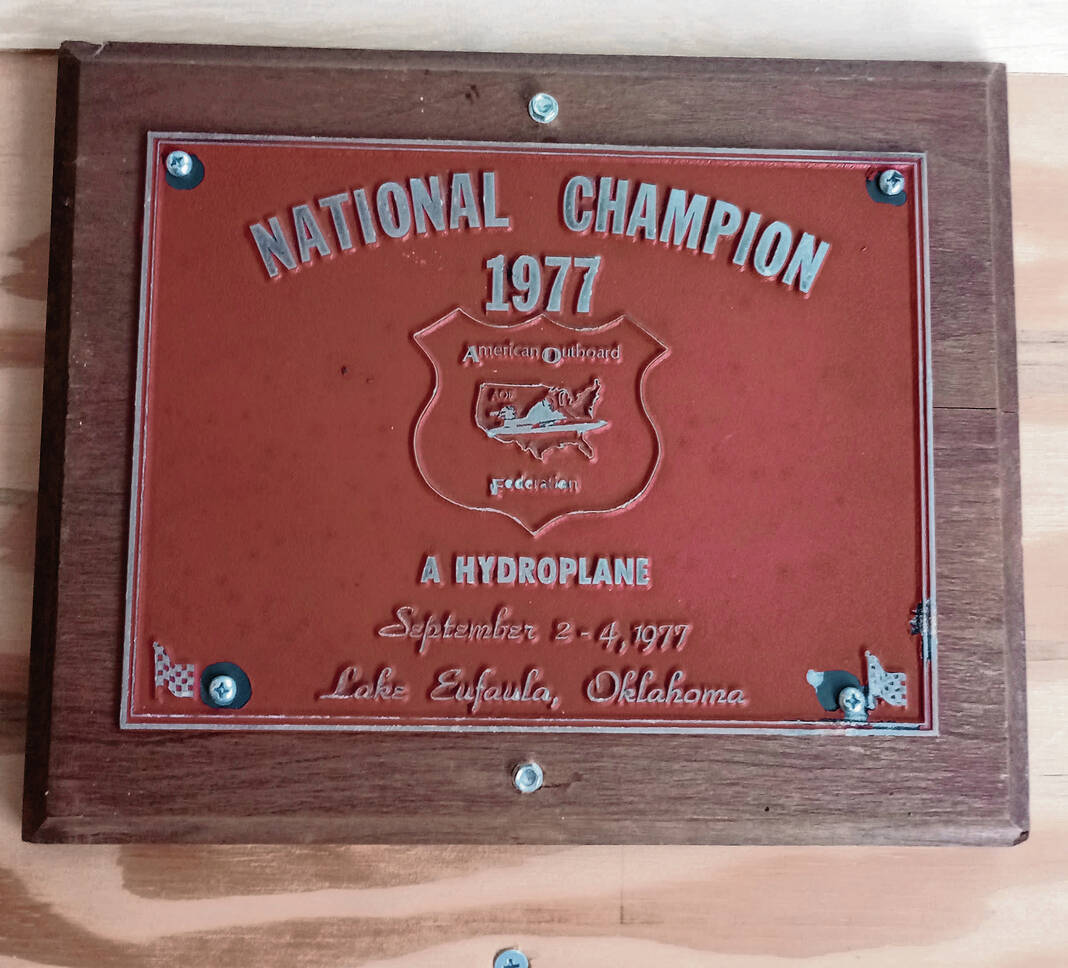

A plaque commemorating Bill Everhart’s national championship victory in Oklahoma in 1977 is mounted on the wall of the trailer Blake uses to transport his boat to races.

Submitted photo

Bill Everhart, racer Blake Everhart’s father and hydroplane racing mechanic, working on the boat on a test day back home in Jackson County.

Submitted photo

Blake Everhart of Brownstown racing in Defiance, Ohio.

Submitted photo

Hydroplane racing at Huntington.

Submitted photo

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

BROWNSTOWN — The difference between hydroplane boat racing and kayak paddling on a lake is pretty much the difference between a NASA space shuttle and a single-engine airplane.

One boat makes waves, the other makes ripples on the surface. One aircraft erupts into outer space, the other dodges clouds. At high speed, the person behind the steering wheel is a rocket man and in kayak and plane he is a lollygagging, sightseer.

“Trust me, with your butt two inches off the water going 70 mph, it feels like 200,” said Blake Everhart, a hydroplane racer and a Jackson County conservation officer with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources. “That boat is a rocket ship. Water speed and land speed are two different animals.”

To many Hoosiers who rent pontoon boats or purchase bass fishing boats, hydroplane racing is only a vague concept. The top-level unlimited class racers do travel up to 200 mph in their enclosed capsules.

Everhart, a Seymour native, is a mid-range racer in an open hull class. He zips over lake waters at 70 mph, which is much more turbulent than driving the 70-mph speed limit on Interstate 65 outside of Seymour. Heck, a motorboat skimming on a lake or river water at 40 mph will part your hair, blow a baseball cap off the head or provide a wind chill factor.

Except for being on water instead of land, hydroplane racing has more in common with automobile racing than boat touring. For one thing, ear plugs can be useful in terms of muffling the sound of engines.

“We make a little bit of a racket,” Blake said.

Everhart, 41, is in his third season of racing and has upgraded his boat and emergency safety gear, indicating he is taking competition more seriously. His mental background, however, in the comparatively little-known sport which has strongholds in select regions of the country, dates to childhood.

Dad Bill Everhart, 68, also of Seymour was a hydroplane boat racer for a few years in the early 1970s — and even won a national championship — before injuries suffered in an auto accident benched his career. Now he serves as Blake’s chief mechanic, and both are members of the Indiana Outboard Association.

“He used to have trophies around when I was a kid,” Blake said.

A few years ago, at the Indianapolis Boat, Sport and Travel Show, the younger Everhart stumbled on the association’s booth.

“My dad used to race one of these boats,” he told staffers, who handed him a brochure and suggested, “Come to the driver school.”

The driver school? For $50, a one-hour class was offered, followed by an opportunity to drive a boat. That was 2018. Everhart did it all over again in 2019, and then bought the used instructional boat he learned on.

Now that boat lives in a garage and has been replaced by a slicker model. It was built in February 2023, the marking carved into wood on the inside, seemingly duplicating a winery label for a vintage.

In summer, and into October, Everhart visits lakes around the Midwest for weekend races, hauling the narrow, brightly colored green-and black-boat with “Blake Everhart” stenciled on the side. The colors are the same as a Kawasaki dirt bike he owned when younger.

Competitors on the circuit are getting used to seeing Blake’s hydro splashing past. Races convene in Dayton, Springfield, Defiance and Delaware, Ohio, Huntington, Indiana, Constantine and Hillside, Michigan, Danville, Illinois and elsewhere. The sport is prominent in the Pacific Northwest, with its history of super-fast racing, and where the engines may be helicopter turbines, but this region is also a hot spot.

His favorite race of the season was the short course in Huntington and Blake hopes talk of adding another Indiana race, at Hardy Lake, comes true next year.

The events last two days, with two heats on courses of roughly three-fourths of a mile to a mile. In early September, Everhart experienced the highs and lows of racing in the same weekend.

On the Saturday, his wooden boat’s engine coughed through a mix of mechanical difficulties, and he could not challenge. On Sunday, he won heats. The good, the bad and the ugly summarized.

Connected to the past

While Everhart’s boat competes in what is called Class C, the middle of the pack, and is about 11½-feet long, with a cockpit just 16½-inches wide, there are many kinds of hyrdos around the globe, with racing in Asia and Europe.

Grand Prix racing boats are powered by V8 piston engines that can run at 1,500 horsepower. Those boats, which race in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, are 23-to-26 feet long, topping 170 mph.

The weight for Everhart’s class is 440 pounds. That includes the engine and his body weight, which he put at 155 pounds. The boat itself is not terribly heavy and can readily be lifted by two adults. If boats are too light, they must carry extra lead, much as a thoroughbred racehorse is required to carry artificial weight if its jockey is too light.

When a clock countdown of three minutes begins, the racers start their engines. Over the next few minutes, they work up to speed while positioning in an assigned lane, then attempt to hit the start line at the precise second the clock hits zero. That block of time is called “milling,” or what an orchestra would call a vamp-till-ready.

During the run-up, the engines may be at their noisiest, with the loudest roars. Once racing begins, they simmer down more to the sound of a group of bumblebees.

Before transporting boats hundreds of miles, considerable testing and fine-tuning takes place. Inside that haul trailer, a plaque is nailed to one wall. It was the award Bill Everhart received in September of 1977 when he won a national championship in Eufaula, Oklahoma.

When Bill raced, he lived in Seymour, close to the East Fork of the White River, and tested there.

“I used to get on my bike, run up there and watch them,” Blake said.

On non-workdays, the Everharts seek good water to test between races. Bill might be called “an expert advisor,” or a coach, helping with the background gained from his five years racing.

The sport has matured some. Bill said drivers often raced wearing cut-off shorts or blue jeans wearing open-faced helmets.

Blake races in heavier-duty helmets and a full-body Kevlar wetsuit under his life jacket. Much like Indy Car and NASCAR racing, hydroplane racing once produced many fatalities. Those high-speed sports have seen tremendous safety advances. Blake Everhart invested in all new, state-of-the-art safety garb before this season.

“It was an upgrade, big-time,” he said. “I even wear Kevlar socks.”

Bill Everhart said conviviality between drivers has improved. When he raced, the attitude was more cut-throat and “people were not above throwing dirt in your carburetor. People help you out a lot more these days.”

While Blake said his No. 1 attraction to the sport is the speed, the other reason he enjoys hydroplaning is the people. The sport has a minimum junior class of nine years old, but there are some veterans still competing in their 80s.

“You meet people from all over the country,” Blake said. “It’s competitive, but we’re all friends in the pits.”

It’s not about getting rich because there is no prize money at stake, only sometimes cash paid out from a collection bucket that probably won’t cover the cost of the trip.

Steadily improving

No room for passengers on a hydroplane boat. The boat is made of wood, the cockpit is made of wood, stretching several feet behind the driver.

One surprising element for those who don’t know hydro is that the driver is not seated in the cockpit, but steers while on his knees, bracing his body on a cushiony type mat.

Everhart’s engine may be loud, but the fin in the water goes only several inches deep. The idea is to stay on the water surface, maintaining balance at high speed.

“That fin is what keeps us from barrel-rolling,” Blake Everhart said.

Recently, Blake Everhart was ranked nationally in his competition class out of about 50 boats or so, satisfactory success.

“I’m tickled with that,” he said.

Fun for all ages, apparently, bridging the generations, with Blake and senior advisor Bill sharing the road time and the race time.