These four motorcyclists from left, Aaron Brown, Pastor Scott Brown, Doug Kiste and Ryan Brown, stopped along the James W. Dalton Highway aka The Dalton during their recent trip from Seymour to Prudhoe Bay in Alaska.

These four motorcyclists from left, Pastor Scott Brown, Ryan Brown, Doug Kiste and Aaron Brown, stopped along the boundary to the Arctic in Alaska during their recent trip from Seymour to the Arctic Ocean.

Motorcyclists, Pastor Scott Brown, Aaron Brown, Doug Kiste and Ryan Brown, take a break during their recent trip from Seymour to the Arctic Ocean in Alaska.

Motorcyclists, Pastor Scott Brown, Aaron Brown, Doug Kiste and Ryan Brown, take a break at Atigun Pass through the Brooks Mountain Range during their trip this summer from Seymour to the Arctic Ocean in Alaska.

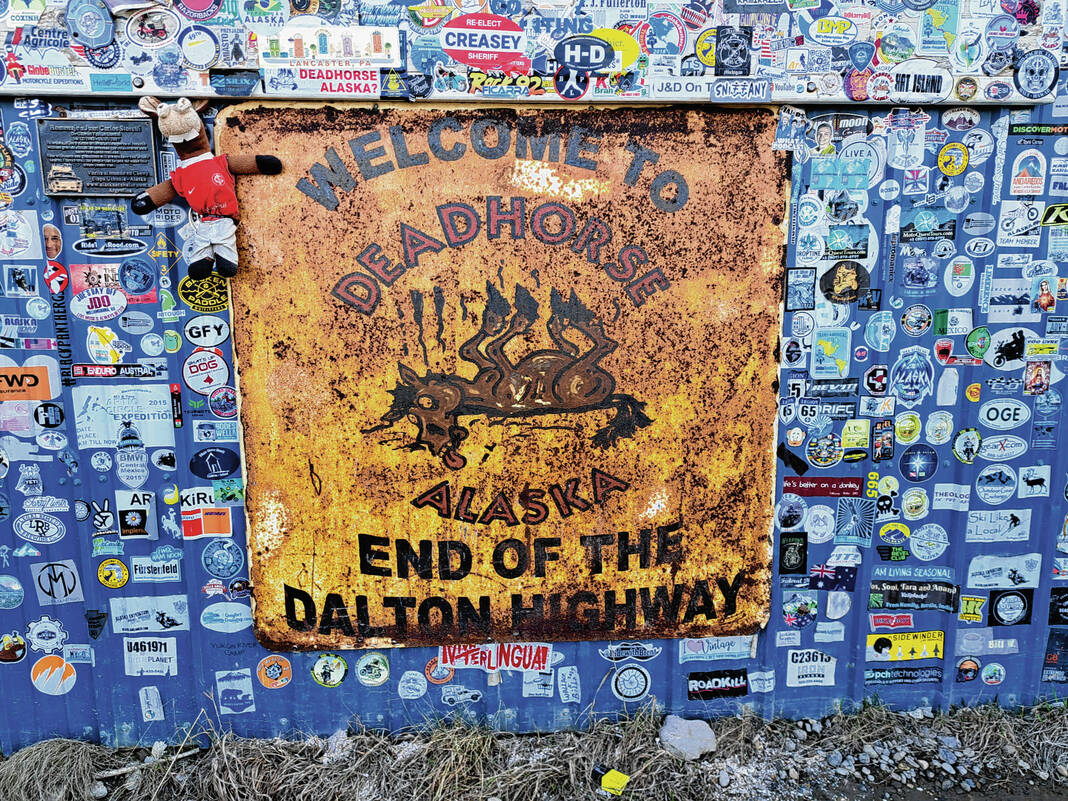

This sign welcomes visitors to Deadhorse in the Prudhoe Bay area just south of the Arctic Ocean.

These four motorcyclists from left, Pastor Scott Brown, Aaron Brown, Ryan Brown and Doug Kiste pose in front of the Arctic Ocean during their recent trip from Seymour to the Arctic Ocean at Prudhoe Bay.

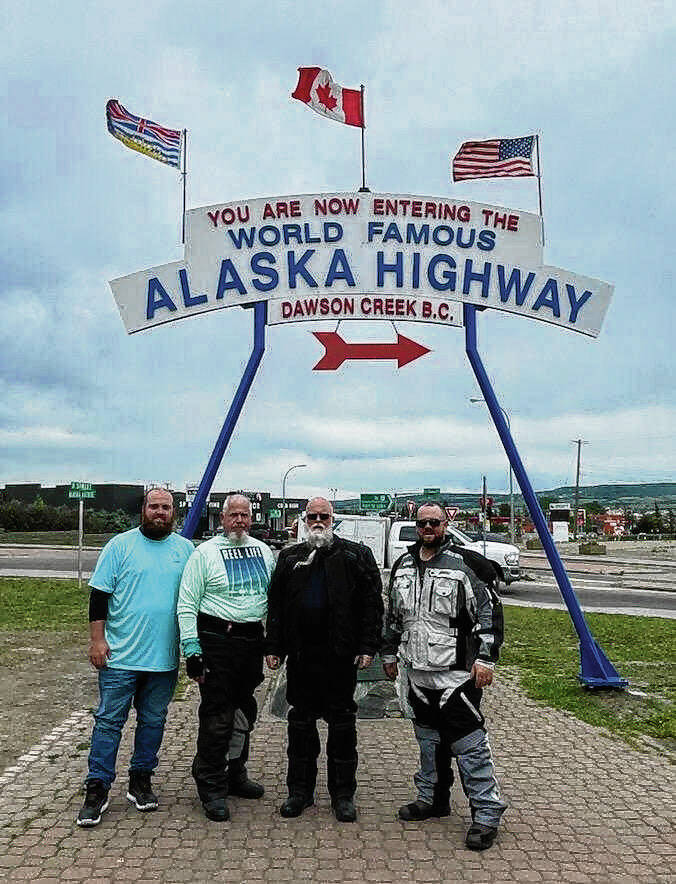

These four motorcyclists from left, Aaron Brown, Doug Kiste, Pastor Scott Brown and Ryan Brown, stopped at the entrance to the Alaska Highway at Dawson Creek in British Columbia, Canada, during their recent trip from Seymour to Prudhoe Bay and the Arctic Oceanin Alaska.

These four motorcyclists from left, Aaron Brown, Doug Kiste, Pastor Scott Brown and Ryan Brown, stopped at the entrance to the Alaska Highway at Dawson Creek in British Columbia, Canada, during their recent trip from Seymour to Prudhoe Bay in Alaska.

The minister of a local church and a church elder who have been riding motorcycles across the country for years was able to check an item off their bucket list earlier this summer.

“We’ve been friends for almost 23 years and riding bikes for that long,” the Rev. Scott Brown said of Doug Kiste, who is an elder with Brown’s congregation at Reddington Christian Church.

Scott, who is 60 and the senior minister at the church, said he and Kiste, who is 61, began talking about riding bikes to Alaska as far back as 15 years ago.

“We were talking about someday riding to Alaska on bikes because we’ve been through a lot of the lower 48 (states).” Scott said. “We’ve been all over these United States on two wheels.”

Aaron Brown has been on a couple rides with his dad and Kiste in the past, and Scott has completed other rides with Aaron, who is 32 and lives in Lebanon, Kentucky, and Ryan Brown, who is 35 and lives in Seymour with his family. The Browns also have another son, Evan Brown of Seymour and daughter, Abbie Kindred, also of Seymour.

“We’ve all traveled some, but Doug and I have traveled the most together,” he said.

A couple of years ago, Doug was in Scott’s office and had the idea of riding to Deadhorse and Prudhoe Bay.

“We talked about it being on our bucket list,” Kiste said. “On odd years we ride to a church mission in Montana. So, we knew we couldn’t do it on an odd year. It had to been done on an even year. And this is the first even year I am retired.”

Why Prudhoe Bay?

Scott said the Dalton Highway which connects Fairbanks, Alaska, with Deadhorse and Prudhoe Bay and the Arctic Ocean 471 miles to the north is kind of a famous biker’s road.

“A lot of guys have it as a bucket list,” he said. “If you’re going to ride to Alaska, do the whole thing. It’s the furthest north that you can run on a public road in North America. It (the Dalton Highway) is part of the PanAmerican Highway, which runs from Argentina to Prudhoe Bay.

The decision to attempt to make the trip led to the question of Scott being able to get enough time away from his ministerial duties to do so and he was given that approval, Kiste said.

“So, we needed to schedule this before we get older,” he said.

Scott said the thought was if they didn’t get it done, they were going to age out and not get it done.

“So it started out it was just going to be Doug and I but the boys jumped on,” he said.

” … and we’re glad that they did,” Kiste said.

“It made it a lot easier having that support base for us,” Scott said.

Ryan said the trip even at his age, however, didn’t go as expected.

“I think we were all under the expectation we were going to hop on our bikes, ride up there, turn around and ride home … and it was much harder,” he said.

Scott agreed that the trip of 9,473 miles in 21 days was a lot more challenging than anticipated.

But having the younger guys made it a lot easier when they had to pick the bikes up, which had often, he said.

After leaving Seymour on the morning of June 18, the four headed northwest toward Pinehaven Christian Children’s Ranch in St. Ignatius, Montana, which is about 1,850 or so miles from Seymour. Scott, Aaron and Doug all rode BMW GS while Ryan rode a Suzuki V-Strom XT.

That trip took about two half days to complete, and involved rides of 750 miles or so riding the first day to St. Cloud, Minnesota, and about 800 more miles the second day to Billings, Montana. Both trips required riding on the bikes for about 14 hours.

Sopping at St. Ignatius the third day gave them a chance to sleep in something besides a tent. For the record, however, they only slept in tents on the ground for seven nights throughout the trip. They stayed in a motel a couple of nights and the rest they stopped at Airbnbs.

There’s was another advantage besides a good night’s sleep for stopping in Pinehaven in northwestern Montana.

“A friend of ours at Pinehaven, they have some commercial freeze dryers so we stopped and bought some freeze-dried meals from him to take with us because we knew there were going to be times when we would need them,” Scott said.

After leaving Montana, the four headed northwest toward the Alaska-Canadian Highway, better known as the Alcan.

“From there you had to be a little bit strategic because places to stay, food and gasoline can be a little sparse, especially when you get up north in the Northwest Territory and the Yukon Territory,” Scott said. “You can be out in the middle of nowhere.”

Kiste said you could find yourselves 200 miles from the next gas station and sometimes if you found a gas station it might have been closed for years despite being listed on GPS. So, the four carried extra fuel on their bikes, which Scott found could be dangerous if you didn’t watch the placement of external fuel tanks on the bike. When they were still in the Yukon, his external tanks were placed a little too close to the exhaust at one time. The one of his external gas tanks melted s allowing fuel to escape and spray the others who were riding behind him at the time.

The incident left them pondering one thing.

“… how the boys were going to call home and tell mom that dad had exploded,” Scott said.

The ALCAN is now all paved, but the pavement is rough in a lot of spots.

“There were times up on the Alaska Canadian Highway that even being paved we were hitting potholes and bottoming out the bikes,” Ryan said.

At Fairbanks, the four switched out their on-road tires for off-road tires, which they had ordered beforehand, changed oil, check the bikes over and contacted a sister Christian church the that held their camping gear.

“Once we left Fairbanks and headed north up into the arctic, we did not camp,” Scott said. They still had to carry their food and clothing.

After spending Friday night in Fairbanks, the four headed off on the James R. Dalton Highway, which is unpaved for the most part except for the last 20 or 25 miles before Deadhorse. That stretch is also in the tundra which requires more stringent construction.

They overnighted at Coldfoot, which is about the highway point between Fairbanks and Prudhoe Bay, but it still took them 10 hours.

“Because on the Dalton you’re running 15 to 20 miles and hours,” Scott said.

“If that,” Aaron added.

Scott said riding 230 miles or so at that pace leaves so physically and mentally exhausted to do the whole 471 miles to Prudhoe Bay in one day would have been very difficult. That’s despite the fact that the sun never sets in the summer there.

“You can’t tell much difference between 3 o’clock in the afternoon and 3 o’clock in the morning,” he said.

The second day of the two-day trip to Prudhoe Bay was much worse because it passes through the Brooks Mountain in Atigun Pass.

Most of the Dalton is gravel, covered with calcium chloride, that makes it really hard when it’s dry.

“But when it’s wet, it’s like driving on slime,” Scott said. There are other stretches where highway crews are not spraying calcium-chloride but spraying it water to keep the dust down.

“So, you have these massive stretches where it is slicker than anything,” Scott said. “It’s worse than ice. Then you hit where it’s rutted you could be feet deep where it’s almost impossible in some of those stretches to get motorcycles through.”

The end result is everyone drove a whole lot slower especially when their bikes were loaded down with camping gear.

“At some point in time all four bikes had to be picked up,” Scott said.

At Prudhoe Bay, the lodgings consist of prefab units that are stacked up on top of each and attached to each other.

The units don’t look too nice from the outside, but they are pretty nice because they house oil field workers, and their employers want to keep them happy.

“You walk inside and it’s like you’re in a four- or five-star resort,” Ryan said. “They have all the food you can eat.”

To get to the Arctic Ocean, you have to pass through security at one of the refinery gates. The cost for that trip was $80.

It wasn’t cold at all unless you were in areas where there was ice in pond or lakes in the area.

“It was very surprising to me,” Ryan said.

There wasn’t anything to do in the Prudhoe Bay-Deadhorse area because it mainly camps for the oil fields.

“They won’t let you go out and walk around because of the bear threat,” Aaron said.

There’s also the threat of wolves. Scott said.

After returning from the trip to the Arctic Ocean, the four headed back toward Fairbanks.

Before making it back to Coldfoot, Aaron’s bike caught fire leaving with $8,000 in damage parts alone.

“It burned the brake pads off,” Aaron said. “We got the brake caliber off the rotor.”

The bike could be repaired enough that Aaron could limp back to Coldfoot that day and back to Fairbanks the next — without any rear brakes. Aaron sold it the motorcycle and caught a flight home.

The other three made the return to Seymour with each carrying a third of Aaron’s luggage.

“I threw away some of my stuff,” Aaron said. “I send some of it back with them. I took some of it back myself.”

He looked into renting a trailer to bring everything back, but it was going to cost $5,400, Aaron said.

All four agreed they would do the trip again, but perhaps in a separate way.

“If I do it again, I’m taking my Jeep,” Scott said.

Aaron said he would do it on more on something more like a dirt bike.

It was fortunate that no one got hurt during the 21-day trip.

Their advice to anyone considering a similar trip should plan ahead because you have to purchase health insurance for travelers.

“Our American policies wouldn’t have done us any good,” Scott said. “We had to get some Canadian money.”

Aaron said you also have to plan for different scenarios that might crop up.

There’s also a need for taking spare parts.

And if you decide to cross into the Arctic there’s something else you need to watch out for.

“Mosquitoes,” Aaron said. “When you cross into the arctic mosquitos swam you. The second you stop, they come out of nowhere.”

Their emergence led them to wear netting and called for long sleeve shirts.

“Overall, we were blessed for having done it,” Scott said. “We’re happy we did it, but we’re happy we our truly happy to be home.”

“It was a lot more work than we anticipated,” Kiste said.