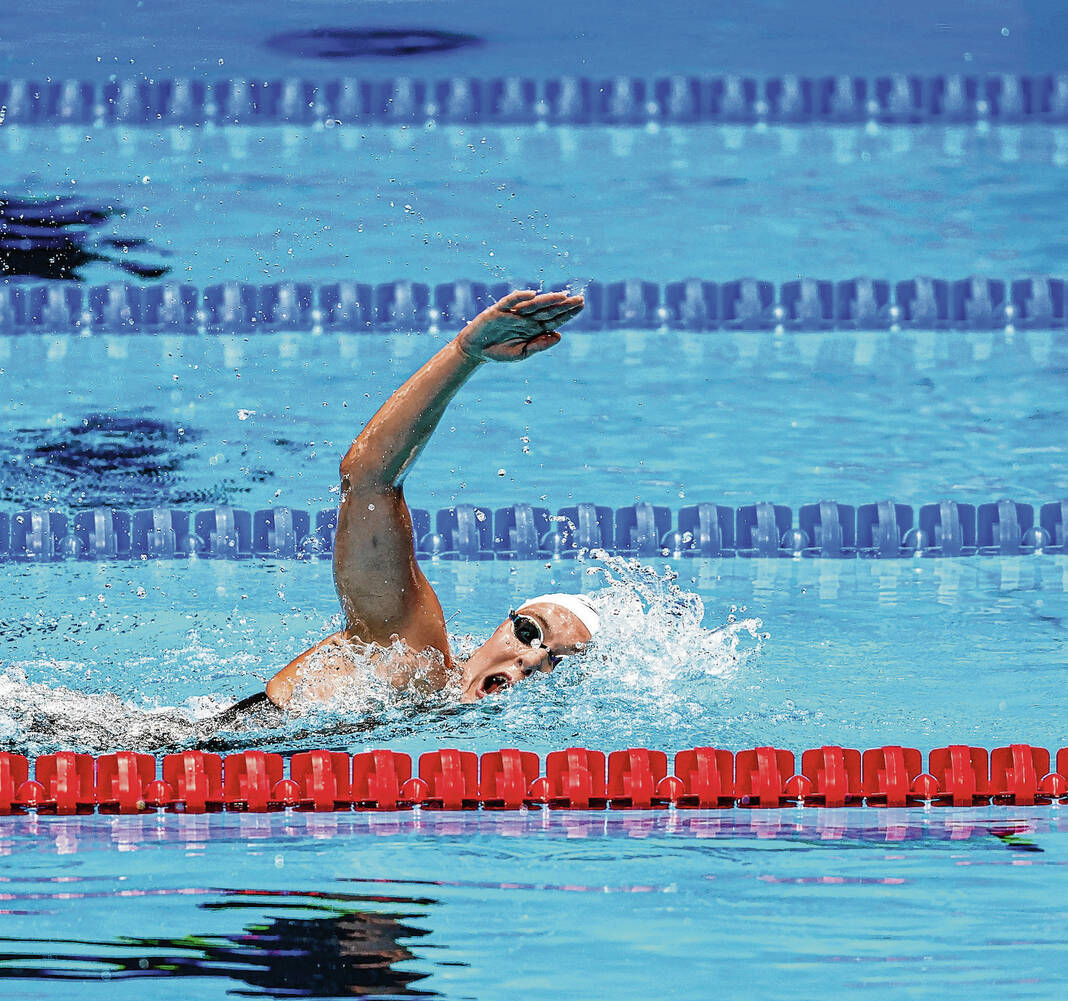

Marian Denigan of Indiana University will compete in the open-water swim at the Paris Olympics.

Submitted Photo | Indiana University Athletic Department

Cory Chitwood, an assistant IU swim coach, is an assistant coach for the U.S. open water swim team for Paris.

Submitted Photo | Indiana University Athletic Department

If Mariah Denigan wins a medal at the 2024 Paris Olympics, she might well adopt a new theme song commemorating her 10 kilometers of coping with the Seine River.

In 1965, the singing group the Standells, recorded “Dirty Water” as an insult to Boston’s Charles River and Boston Harbor, yet it became a cult classic and most Boston professional sports teams play the tune after a victory.

This summer, the open-water swim in the Games has been scheduled for the Seine River. While the goal was somewhat romantic, highlighting a well-known geographical feature of host country France, and offering expansive views of the competition, the underlying problem is the health of the river.

Freedman

Freedman

The 483-mile Seine is somewhat polluted. It has been afflicted in this manner for some time, apparently going back to 1924, when Paris last held a Summer Games and someone had the same idea of performing events on the river.

Denigan, 21, one of several Indiana University-connected swimmers and divers competing for the United States, has tested the waters in open-water swimming all over the world in recent years. That includes Portugal, Japan, Hungary, Italy, Qatar and the Seychelles – her favorite wet stopover.

“It’s no news to anyone the Seine is kind of disgusting,” Denigan said. “I don’t want to be sick after.”

A reasonable goal beyond a medal.

Swimming has always been a major component of the Summer Olympic program, but mostly in a pool. Any athlete who has ever swum competitively in a lake, the ocean, or yes, even a river, learns quickly this type of swimming is a different animal.

The length of an Olympic-sized pool is 50 meters and it is set in a very controlled environment. The circumstances for the 10-kilometer outdoors can change by the minute. There may be wind, warm or cold-water temperatures, waves smacking the swimmers in the face, a rocky bottom, or absolutely clear water, though probably not sharks interfering.

“It all comes back to flexibility,” Denigan said.

Meaning the swimmer’s approach, awareness conditions may differ from race to race, unlike at a pool where the situation is very static. Denigan also swims in pools, longer freestyle events, so she can compare.

When the modern Olympics revved up in 1896 in Athens, Greece, all of the swimming was contested in open water, but that was it for more than a century. This open water 10-k event is called “a marathon” of swimming and was introduced in 2008.

Even though it is maturing as part of the Olympic program, open-water swimming receives a fraction of the attention of pool swimming and few fans understand all the permutations required to cope with the water.

When Cory Chitwood, associate swim coach for IU, and an assistant Olympic open-water coach, was asked if the public understands the event, he did not hesitate.

“Do people get it? No.” Chitwood said. “It’s probably one of the most grueling events in the Games.”

Open water is growing in popularity, he said. “It’s massive in Europe,” he said.

Chitwood made it sound as if the competitors might even body check one another in the water in the middle of the race and also if the average fan attempted to swim the 6.2 miles they might drown, or at least give up.

“To me, if they swim that far, it takes someone special,” Chitwood said.

Open-water swimming is to the pool as running a marathon on the streets is to a track in a stadium. They may be members of the same families, but are no closer on the family tree than cousins.

It’s pretty much a given an Olympic competitor going for a medal will be nervous before her event – the open-water is set for Aug. 9 and 10 – but water conditions and water quality will be on Denigan’s mind, too.

There has been talk Olympic organizers have an alternative site for the races if the Seine is deemed too polluted.

“Fingers crossed, I’m hoping there is a secret back-up,” said Denigan, saying she has heard Games organizers might have a Plan-B-lake in mind.

Denigan has visited some unique places for open-water competition.

“You’re always in a beautiful location,” she said and the athletes know each other well. “It’s so small. It’s so tight-knit.”

The Seine sounds like a cool place to race with the fan friendly environment, but not if the water is dreadful. Unlike in the 50 freestyle, swimmers must breathe regularly in a 10-k.

Denigan’s favorite competition place was the Seychelles Islands, Africa’s smallest country with more than 100 islands in the Indian Ocean, and one, by the way, where one official language is French.

“It’s a honeymoon place,” Denigan said of how she remembers the Seychelles. The race featured such clear water swimmers could see bottom the entire race.

Maybe given that French language connection, and being the opposite of “Dirty Water,” the Seychelles can pinch-hit for the Seine in the Olympics.