By Song Li

Guest columnist

Aunt Peng had a stubborn streak, an unyielding adherence to her principles, something we call “often being stuck” in our Beijing dialect. I gained an early intuitive sense of the number 2 from Aunt Peng, long before it became a popular notion.

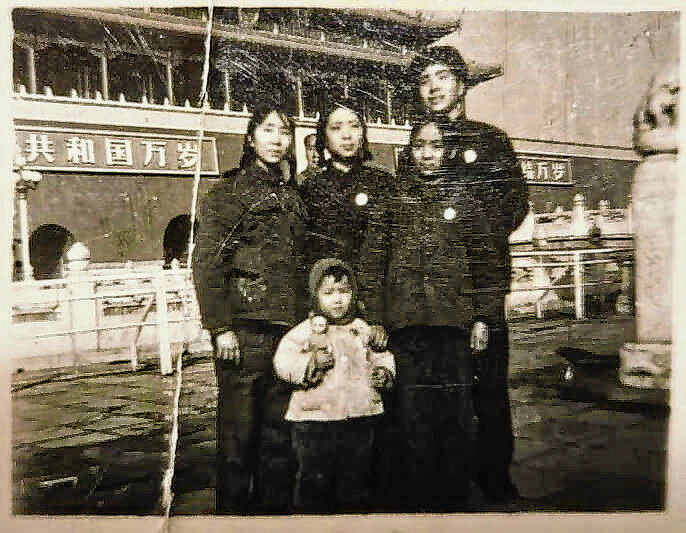

Because my mother was the eldest sister, and my younger aunts all had sons, I naturally became the “big sister” of our generation. I would assert my seniority to my cousins: “I knew your mothers before you did, even before your fathers did!” This was a fact they could not contest.

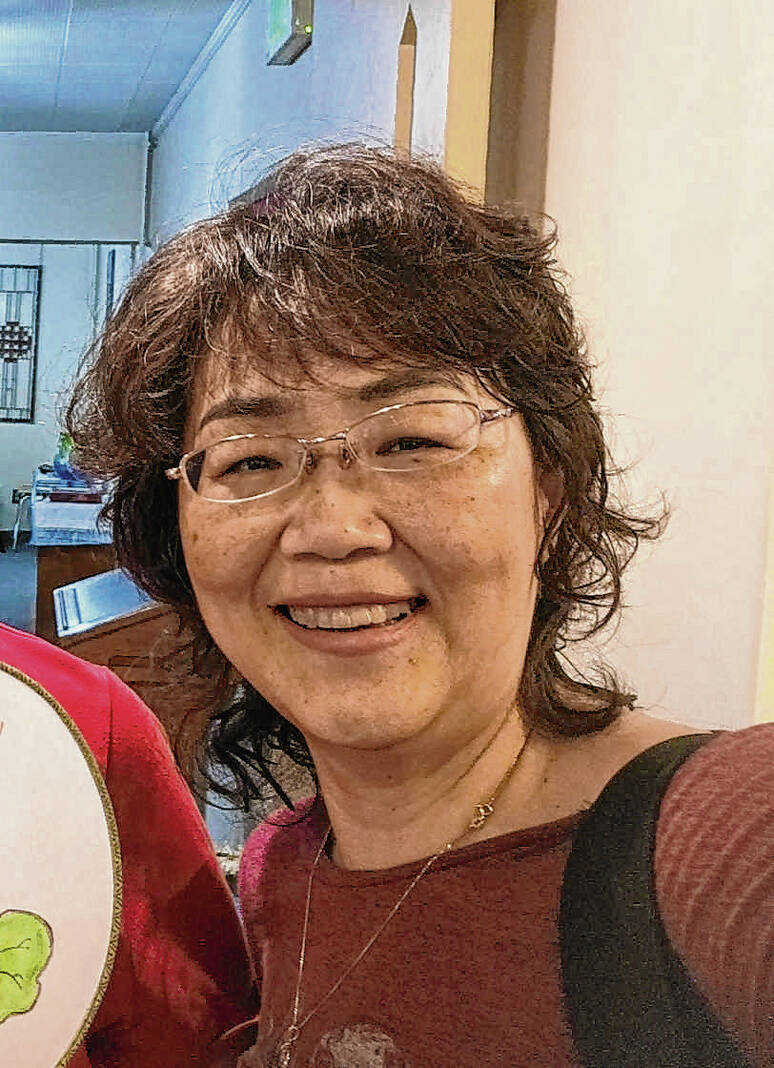

In my memory, Aunt Peng is always in her 20s, with two braids like those of female soldiers in the military corps. Her round face differed from the long faces of her sisters, and her eyes were the largest among the Song family girls. Her skin was a bit rough, weathered by the winds of Inner Mongolia, but her complexion was fresh and rosy. When she smiled, she resembled a sunflower, full and bright. She had a tendency to lower her head, appearing both shy and stubborn, again much like a sunflower.

Aunt Peng was a long-distance runner and a top student. She did everything with perfection. Her aspiration was to become an agricultural scientist, dedicating her youth to the nation’s grain production so that the people would be well-fed. The year she was poised, however to take the college entrance exam, it was canceled.

Soon, Aunt Peng found herself in Inner Mongolia. Concerned about her younger brother, who had been sent there after middle school, she decided to go too, hoping they could look out for each other. In reality, they were assigned to different pastures. She worked hard to integrate with the local herders, but at night, the drunken herders would circle her yurt on horseback, singing and shouting, leaving Aunt Peng shivering in the dark. After an indeterminate period, she desperately wanted to return to Beijing, but it proved to be as difficult as ascending to heaven. She eventually married a farmer from the outskirts of Beijing, using this as a means to return to the city’s outer suburbs. Ten years had passed by that time.

Her husband was two years younger than she was, different from the usual portrayal of young, educated women marrying old farmers in TV dramas, yet the gap in their intellectual worlds was just as vast. Aunt Peng’s brow was often furrowed, her round face rarely smiling anymore. Fortunately, she soon had a chubby son. I remember coming home from kindergarten and seeing Aunt Peng, who I hadn’t seen in a long time, sitting on my grandmother’s bed with a dark-skinned, chubby boy in her arms, the type who would naturally be nicknamed “Doudan” (which literally means “Dog Egg”). I immediately eyed the milk bottle beside them, craving a taste. Aunt Peng, good-natured as ever, handed it to me, but after one sip, I made a face and ran off, realizing it wasn’t like cow’s milk. Now that I think about it, I had taken Doudan’s food.

Aunt Peng finally got a chance to take the college entrance exam. She studied intensely in our small house for two solid weeks, driven by her perfectionist spirit. Time was short, and too many years had passed since she last studied. She went into the exam underprepared and, unlike the stories depicted in movies, she did not emerge with top marks. I couldn’t understand why she only had this one chance; the harsh reality was that Aunt Peng did not succeed.

It seemed as though Aunt Peng had walked into the wrong room, ending up in the lowest rungs of society, which became her permanent place. Neither she nor her husband had educational qualifications, and her husband lacked urban residency status, limiting them to menial labor. Aunt Peng worked as a cleaner in kindergartens, hospitals and other places whose names I can’t recall, doing the lowest-level jobs. I can imagine, though not fully, the brutality of this jungle-like society. The only trace of her perfectionist spirit in her life was seen in the way she cleaned every toilet spotlessly, sorted discounted bundles of leeks by length, and neatly divided vegetables by their green leaves and white stems. Such meticulous sorting would ultimately end up mixed together in the pot. Perhaps, in a daze, Aunt Peng believed she was conducting experiments in a biology lab?

My interactions with Aunt Peng were few. In my memories, she was always busy, endlessly tidying her small, cluttered home. Then I went abroad, and one day Aunt Peng anxiously called me, wanting to discuss Doudan’s future. By then, Doudan had become a talented chef with a promising future, but like all mothers, Aunt Peng still worried. A few years later, when I returned to China, I found her back bent. A few more years later, her teeth were gone. I urged her to get dentures, but she brushed me off with a smile, focusing instead on discussing Doudan’s marriage, hoping I could help. Despite Doudan’s good rapport with the opposite sex, Aunt Peng, like all mothers, couldn’t keep herself from worrying.

In our family WeChat group, Aunt Peng occasionally forwarded red songs or similar posts, reflecting an unshakeable mark unique to her generation.

Reading Chi Pang-yuan’s book about her return to mainland China and the state of her old classmates, I thought of my Aunt Peng. She had come the closest to success among her sisters but missed it by a whisker, like a lottery ticket that missed the winning number by one digit, making her story all the more poignant. If Aunt Peng had gotten into university, her whole life would have been different.

News stories about Chinese seniors singing red songs and dancing on luxury cruise ships, disturbing other passengers and fighting for food, reminded me of Aunt Peng, though she had never been on a cruise, never fought for anything and never bullied anyone. The media’s derogatory terms were aimed at her contemporaries, people who breathed the same air of an era, who had once been fresh, upright, and hardworking. My overall feeling towards this generation is more of pity than criticism. In some circumstances, they might disrupt civilized order, but who disrupted their destinies first?

Time never stops; it takes away youth and laughter, and brings aging and separation. As I type these words during the deep night in the United States, Aunt Peng is in the twilight of her life in Beijing.

She started dialysis last year, and though there were moments of improvement that allowed her to return home, dressed in festive red to celebrate the New Year with her old friends. We all thought she could last another decade with thrice-weekly dialysis. After all, there were many such cases, and she was only 77 not considered old by today’s standards. In March, however, her condition took a sharp turn for the worse. Doudan, now living in Hong Kong, flew back to Beijing every Friday to be with her. He returned to Hong Kong on Sundays, disregarding work, rest, and expenses, wanting only to spend more time with his mother. Money flowed like water, and Aunt Peng’s condition fluctuated.

Last August, I returned to China and visited Aunt Peng at home. She was emaciated, but warm and lively, her round face still resembling its old self. This May, when I visited her in the hospital three times, she was even thinner than skin and bones. She would open her eyes slightly to look at me, nodding, and trying hard to call my name. I combed her hair, careful not to touch the pressure sores on her earlobes, which were massive scabs that would not heal. When the caregiver helped her turn over, I saw that her legs had become stick-thin. While she was often very quiet, passively enduring life, I knew that she was still encouraging herself inside, as she had always done: to strive, to be strong, to conquer illness, to get better.

In the last few weeks, her condition deteriorated steadily. Kidney failure was followed by liver failure. Bedsores and diarrhea ensued. A 14,000 RMB Yuan injection to lower bilirubin had little effect, and she cried out for her father and brother — both of whom had been lost to her for years — in her agonized stupor. Her life’s attachments, efforts, and struggles had largely come to naught. She had spent a lifetime fighting destiny, waging each battle earnestly, yet it was all in vain. Her only solace and pride was her incredibly filial and considerate son.

One of my aunts, who always mixed up God and Jesus, began attending church, asking an unfamiliar pastor to pray for Aunt Peng. From across the ocean, I requested prayers from American and French friends, asking for God’s mercy to release Aunt Peng from her suffering.

Life isn’t always a blessing; sometimes it becomes a torment. As her family, we didn’t want her to suffer, so we preferred her departure.

Peng, my aunt, Peng. She loved long-distance running, excelled in academics, wanted to be an agricultural scientist, cleaned toilets until they shone, and meticulously arranged discounted vegetables like soldiers on parade. At this moment, in the throes of death, tortured by excruciating pain, she clung to life tenaciously, refusing to let go. In my heart, I said, “Aunt Peng, you have fought this life’s battle; old soldiers never die, they just fade away.”

As I finished writing, another aunt sent a message: Aunt Peng passed away at 1 p.m. June 22, 2024 in Beijing, China.

Song Li lived in Seymour from 2015 to 2019 at Sam’s Circle, next door to Pastor Van, who passed away a few months. She relocated to Avon in Hendricks County because of her job and now works for Allegion (Schlage) as an electronic commodity manager. Li said the time after Seymour went through the era of COVID-19 and seems longer than it should be. I miss the tranquil life of Seymour. The highlights of her Seymour memories are the Jackson County Public Library, Seymour Tribune, Pastor Van and Rail’s Craft Brewery. She occasionally wrote columns for The Tribune during her time here. Send comments to [email protected].