Although tourists try to take selfies, the National Recreation Area warns people not to get too close to wild bison.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

“Fluffy cows” has become a joking term for bison where authorities warn tourists away from the 1,500-pound animals.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Andy Spalding wood working for repairs at the Homeplace at Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area where there is an 1850s-style working farm.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

The bison herd can be elusive and then appear only behind fencing at times.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Many members of the Land Between the Lakes bison herd came out of the woods to be seen by the public, but didn’t get close to the fencing enclosure

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Fishing guide John Morgan in his 20-foot boat on Kentucky Lake.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Fishing can be hot for bass and crappie on Kentucky Lake.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

If a visitor can’t see an elk in the wild at the Elk Bison Prairie, there is always a mount to admire at the Golden Pond Visitor Center.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A rescued bald eagle lives in a cage-like structure at the Woodlands Nature Station after it was shot in upstate New York.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

The history behind the creation and evolution of Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area is explained in a timeline at the Gold Pond Visitor Center.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Ducks in a row at the Homeplace 1850s farm.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A whitetail deer at the Woodlands Nature Station. Other deer roam freely through the 171,000 acres.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

One of the 1830s-1850s buildings at the Homeplace at Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area in Kentucky.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Another old-style building at the Homeplace.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A mix of colorful flowers dot the landscape at Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A sign welcoming visitors to the 700-acre Elk & Bison Prairie and a 3.5-mile driving loop.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

)A horse at the Homeplace farm seems to prefer the vegetation on the other side of its corral.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Wild turkeys abound at Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A sheep chowing down at the Homeplace.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Keeping in character, a woman sewing in period dress from the 1850s era Homeplace farm.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Turkeys are hunted on the property, so they have a distrust of humans.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

Although it is probably more common to see threats from bison on signs, Land Between the Lakes has this warning sign about getting too close to turkeys, too.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

GOLDEN POND, Kentucky — “Do Not Pet The Fluffy Cows.” The stickers advertise wise advice to visitors headed into the 700-acre Elk Bison Prairie at the Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area.

Not unless you wish to be head-butted back across the state line into Indiana and land in a hospital bed.

Bison, aka buffalo, may appear benign, but they do not tolerate humans invading their immediate territory, especially when taking care of youngsters, which they do in late spring.

It is OK to ooh and ah from a distance viewing recently born orange-like calves as they swiftly adapt to standing, then running, and the herd is a main attraction at the 171,000-acre don’t-call-it-a-park land mass just a three-and-a-half-hour drive from Seymour for the 1.8-million visitors annually.

Under the administration of the U.S. Forest Service, sandwiched between Kentucky Lake and Lake Barkley, the adjacent areas of Kentucky and Tennessee features all of the trappings of a national park.

“We are a recreation destination year-round,” said Scott Raymond, a Forest Service public affairs officer. “We’re not a park. We’re not a forest. This place has been lived on. It’s been Forest Service since 1995. This is fresh. Before that it was the Tennessee Valley Authority.”

Land Between the Lakes has an extraordinary back story, but offers fishing on those lakes supervised by the Army Corps of Engineers, hunting, hiking, paddling, a nature station with rescued wildlife, a working farm, horseback paths, bicycle trails, camping, target shooting, a planetarium with all-day programming and wildlife roaming the premises.

“We are surrounded by so many things that a lot of people just do not know about,” Raymond said.

Someone who heard mention of the prairie area said, “They have bison in Kentucky?”

They do. There is no guarantee, however, they can be seen from the road. It is up to the bison, the United States’ National Mammal, designated as such in 2016 by President Obama, how much time they spend blending in the woods in the shade, or showing themselves in the warm sun.

Bison return

Bison have been part of the American mindset for at least 250 years, from how large and hulking they are, to that fluffy coat, and how they were sacrificed to the point of extinction due to westward expansion with only about 100 remaining nationally around 1900.

Buffalo disappeared from Kentucky in 1800 and by 1846 wild elk had vanished. Only in more recent decades both species have been reintroduced.

In mid-June, a sign at the Elk Bison Prairie stated there were 42 elk and 38 bison. That was not up to date because nine baby bison had been born and newborn elk had not yet been counted.

A sign also said the animals were most likely to be seen between 5:30 and 8 a.m. and 5:30 and 7:45 p.m. To enter the fenced enclosure of a 3.5-mile driving loop cost $5.

“It’s all about the timing,” Raymond said. “The other day the entire herd was on the road.”

A few cars moved nearly in tandem with eyes on the grassy hills. Instead, most obvious were enormous piles of scat on the road, some with tread marks. It was not necessary to be a veteran tracker to see the beasts had passed that way.

One, two, three, four loops of searching produced zero bison sightings. Mommas had instructed young bison not to play in traffic and they listened.

On one more driving swing, a bison stood in the grass about 100 yards distant, leisurely browsing the vegetation. It was not close enough to be easily photographed, but was not so far away it could not be recognized.

How it came to be

At the Golden Pond Visitor Center, just down the road from the prairie, stands a full mount of an elk and a bison head is mounted on a wall. The center is located where the town of the same name once existed.

The building contains a planetarium which stresses informational shows about the sky up there and early-evening laser shows.

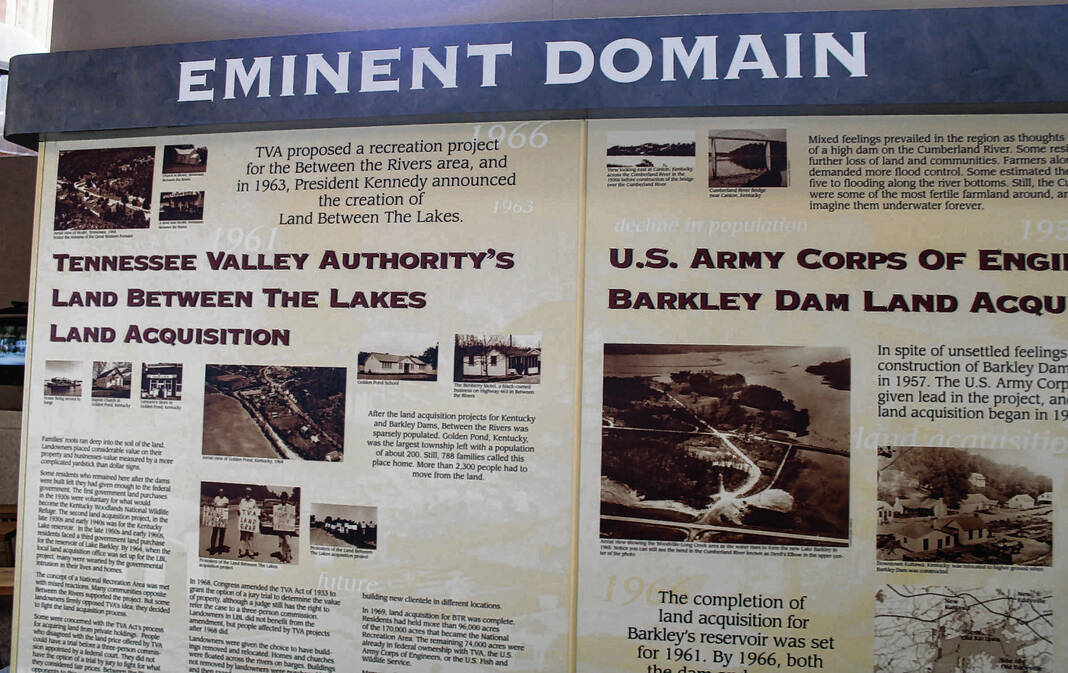

Also on display is a timeline of the detailed history of the way things were and how they got to be what they are.

This land once consisted of Tharpe and Model, Tennessee and Golden Pond, Kentucky by the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers with Confederate Fort Henry on the Tennessee River during the Civil War.

Later, as the U.S. grappled with the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority to provide electricity to the region and to dam frequently flooding waters. The TVA exercised eminent domain in some areas.

Additional eminent domain followed as President John F. Kennedy’s administration labeled the Land Between the Lakes a national recreation area in 1963. Some residents were forced from their land and others found it appealing to sell.

Parallel to this change was the creation of 160,309-acre Kentucky Lake, in 1944, through the damming of the Tennessee River by the TVA.

Lake Barkley, 58,000 acres, was taken over by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1966 through damming of the Cumberland River. That lake is 134 miles long with 1,004 miles of shoreline.

On a recent morning a group of about 40 children, enough to fill a school bus, attended a show at the planetarium as adults wandered the informational exhibits.

Raymond refers to Land Between the Lakes as a fairly new place because it came under full Forest Service purview only in the 1990s. One way it differs from a national park are the 250-plus days of hunting allowed.

“It’s a huge draw,” (for deer and turkey),” Raymond said. “There’s no bison hunting. There’s no elk hunting.”

On that morning, two deer sprinted across one of the 400 miles of \recreational area roads. Several turkeys were spied prowling through the grass.

Two more spins around the Elk Bison Prairie loop, though, turned up zero elk and bison.

Other animals

The Homeplace is an 1850s-style working farm on the grounds, the land dotted with several period buildings.

A woman sewing sat in a rocking chair wearing the appropriate dress for that era. A rooster called. Pigs rolled behind a fence anxious for belly rubs. A horse and mule roamed a pasture, the horse using its nose to reach over a fence with a top horizontal bar knocked off in order to see if the grass really was better on the other side.

Andy Spalding, 40, who graduated from nearby Murray State, chopped wood in the morning sun. He was shaping chunks into appropriate sizes to repair some older chairs.

Spalding said he went to school with the idea of working in art design, but somehow his family knew “I’d never have a normal job.”

Some days, Spalding, who has worked on site for four years, is a blacksmith. Some days, he presents tales of farm life to youngsters soaking up history of the way things were.

A small parade of ducks waddled past his seat and Spalding joked he “had his ducks in a row.”

Saving critters

Many more animals are housed at the Woodland Nature Station. They live in cages for their own protection, otherwise they would not survive in the wild because they somehow have been scarred.

The bald eagle fed a rat for dinner cannot fly. It was shot in upstate New York and transferred here for rehab. There are various owls, a red-tailed hawk, a bobcat, groundhog, coyote, red wolf, some turkeys and deer.

It was feeding time and Lauren, a staff worker, loaded a feeder for whitetail deer with kernels of what she said was a mix of corn and “sweet feed,” usually given to cattle and horses. The deer kept its distance on the other side of the fence, probably waiting until people left.

Fish aplenty

A mist hung over Kentucky Lake shoving off from the Irvin Cobb Marina in John Morgan’s 20-foot boat to fish for bass and crappie.

Morgan, 52, has been a fishing guide for 32 years, but his primary occupation is tobacco farmer.

“That’s how I make my living,” said Morgan, who has fished the lake dating to childhood.

Morgan knows the lake’s twists and turns, and where it becomes Tennessee, even without a marker that the state line is changing.

Over a four-hour stretch he caught and released about 50 fish and a companion caught another 10. The first fish of the day was a 14-inch largemouth bass, surprising Morgan.

“He’s not supposed to be there,” he said. “There’s another one, about the same size.”

The sky turned blue, but the air stayed mild, in the 70s. At times fish bit with energy, coming up one after the other quickly. Then there were long gaps with no bites.

Watching his fish finder, Morgan exclaimed once, “They’re right under the boat.” Instead of casting a distance, lines were dropped straight down. Some white bass were curious enough to bite.

In late morning a fish chomped on a line hard, all signs indicating it was a big one. Some line was taken, then abruptly, the hook sprung free and the fish, deemed a five-pound bass, soared upward.

“That thing jumped four feet out of the water!” Morgan shouted.

From an island perhaps 100 yards away, came the crash of a tree hitting the ground.

“There’s the answer to the question,” Morgan quipped.

Sort of. A tree fell in the forest and someone heard it.

Same type of question could be asked about bison at Land Between the Lakes. If no one sees a bison, are they really there?

On a last driving loop at the Elk Bison Prairie nearing the end of a third day searching, about 15 bison emerged from trees and spread over some high grassland, alternately munching on nutritious greens and resting in the sun.

The fluffy cows, as they had from the 19th century, had returned.