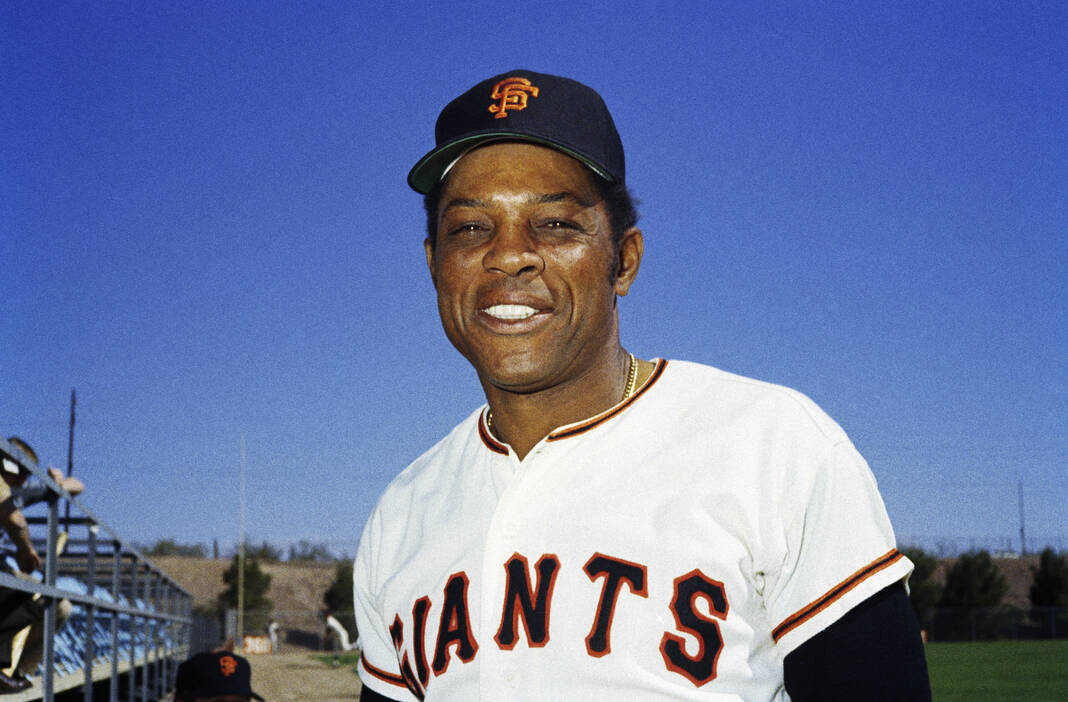

FILE— San Francisco Giants’ Willie Mays poses for a photo during baseball spring training in 1972. Mays, the electrifying “Say Hey Kid” whose singular combination of talent, drive and exuberance made him one of baseball’s greatest and most beloved players, has died. He was 93. Mays’ family and the San Francisco Giants jointly announced Tuesday night, June 18, 2024, he had “passed away peacefully” Tuesday afternoon surrounded by loved ones.

Since the 1950s, Willie Mays has been a magical name in baseball. By the time he retired in 1973, many believed he was the greatest player ever.

Mays wore the uniforms of the New York Giants, the San Francisco Giants and the New York Mets. If you followed the sport at all, you understood Mays had wings on his cleats, glue in his glove and muscle in his bat

While Mays’ place in the firmament of American history is secure, his status as the oldest living Hall of Famer at 93 changed the other day when the native of Birmingham, Alabama, passed away.

Freedman

Freedman

There were two occasions when I had Willie Mays to myself for conversations about baseball. Even then the situations took on tinges of unreality, a voice whispering in my head saying, “I’m talking to THE Willie Mays.”

During the 1980s, when professional boxing was at one of its apexes in the United States and Atlantic City was vying to become the major American city staging big-time fights, I covered boxing as a beat for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

The casinos competed to woo high rollers. One casino on the boardwalk where families had frolicked on the sand and in the Atlantic Ocean for decades, was Bally’s Park Place. A marketing genius convinced the bosses to hire Willie Mays as a greeter.

Mays was retired and Bally’s made him a great offer. Indeed, Mickey Mantle likewise took advantage of a similar offer from the Claridge Hotel and Casino down the street. Only baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn considered their connections to gambling institutions a taint on the game and suspended them from baseball.

Not many recall when Willie Mays was suspended from Major League Baseball, punished for actions claimed to be detrimental to the game. Willie Mays was on baseball’s negative hit list because he chose to accept a $100,000 deal to be himself as an ambassador for an Atlantic City casino. Clearly, the sport’s attitude toward gambling and sports betting has changed since, but at the time it was essentially viewed as the original sin.

I began seeing Mays regularly at fights. At that time, late 1979 and 1980, I saw Mays almost as often as I would have if I had been the Giants beat writer for a major newspaper during his prime playing years.

He was no average spectator. Working at the casino, Mays wore a Bally’s blazer and his picture ID read, “Say Hey, Willie Mays,” as if he would not be recognized otherwise.

I regularly said hello to Willie Mays and Willie Mays said hello back to me. Once, we sat and just talked baseball, a discussion that included him emotionally stating he believed his situation being banned from the sport was absurd.

“I think I should be in baseball doing something,” Mays said. And probably everyone else on the planet besides Kuhn would have agreed.

When asked who were the toughest pitchers for him to hit, Mays’ answer did take a swerve, or a curve. He listed Hall of Famers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale of the Dodgers and Bob Gibson of the Cardinals — and Bob Rush.

The right-hander spent 13 years in the majors, and did make two All-Star teams, but finished 127-152. Bob Rush?

“Well, yeah,” Mays said, smiling at the inclusion of a somewhat average hurler on his list. Rush bothered him, Mays said, because he wore really thick glasses. Mays said Rush’s vision was so bad he didn’t even look in at catcher’s signs. Then he burst out laughing at the cartoon-like image and his being intimidated by such a pitcher.

Mays played with flair and was renowned for his baseball cap appealingly popping off his head as he ran.

“I played for the people,” Mays said. Only a week prior, Mays collapsed from fatigue while speaking to junior high students. Fans inundated him with good wishes and get well cards at the hospital. “That’s love. People saying. ‘We’re very concerned about you.’ It’s a very good feeling.” He was feeling good soon after.

Mays went to work as a special assistant in the Mets’ front office, but those ties were terminated at Kuhn’s behest when Mays signed with Bally’s. Mays met with Kuhn to try to prove his job with the casino was no different than most other public relations jobs and that he had nothing to do with gambling.

Before making that appeal, Mays said baseball had made him feel a little bit ashamed through its ban, even though he felt he had done nothing wrong.

Mays said when his ban was lifted, he wanted a job in the commissioner’s office.

“They go to special events like the All-Star Game and World Series,” Mays said with a twinkle in his eye. “I could do that. That’s what I’m doing now. And that way they could keep an eye on me.”

After Kuhn was out of office and Peter Ueberroth succeeded him as commissioner, the new guy reinstated Mays and Mantle to baseball.

Part II of me and Mays occurred three years later. I was working in Anchorage, Alaska, when Willie Mays showed up signing autographs during a lunch-time appearance at Mulcahy Stadium, the downtown ballpark.

Not that Mays’ legend was unappreciated on the Last Frontier, but it was difficult to imagine him gazing at the snow-capped mountains 3,000 miles north of just about anywhere.

When a man in his 20s waiting in line was asked why he dropped by in the middle of his work day he looked shocked anyone would ask. “Because he’s Willie Mays,” the man said. Because he’s Willie Mays you show up. Because he’s Willie Mays and you don’t know if the opportunity to shake hands with greatness will come again.

Willie Mays batted .301 with 660 home runs and 1,909 runs batted in. He collected 3,293 hits, won 12 Gold Gloves, and became a Hall of Famer in 1979.

After Atlantic City and Alaska I never saw Willie Mays in person again.