Lew Freedman | The Tribune

One-time Louisiana Tech star and former long-time WNBA all-star Teresa Weatherspoon now coaches the Chicago Sky.

One-time Louisiana Tech star and former long-time WNBA all-star Teresa Weatherspoon now coaches the Chicago Sky.

Associated Press

Rebecca Lobo, a college star at Connecticut and in the WNBA, and currently a broadcaster, has had a long and varied career in the sport.

Associated Press

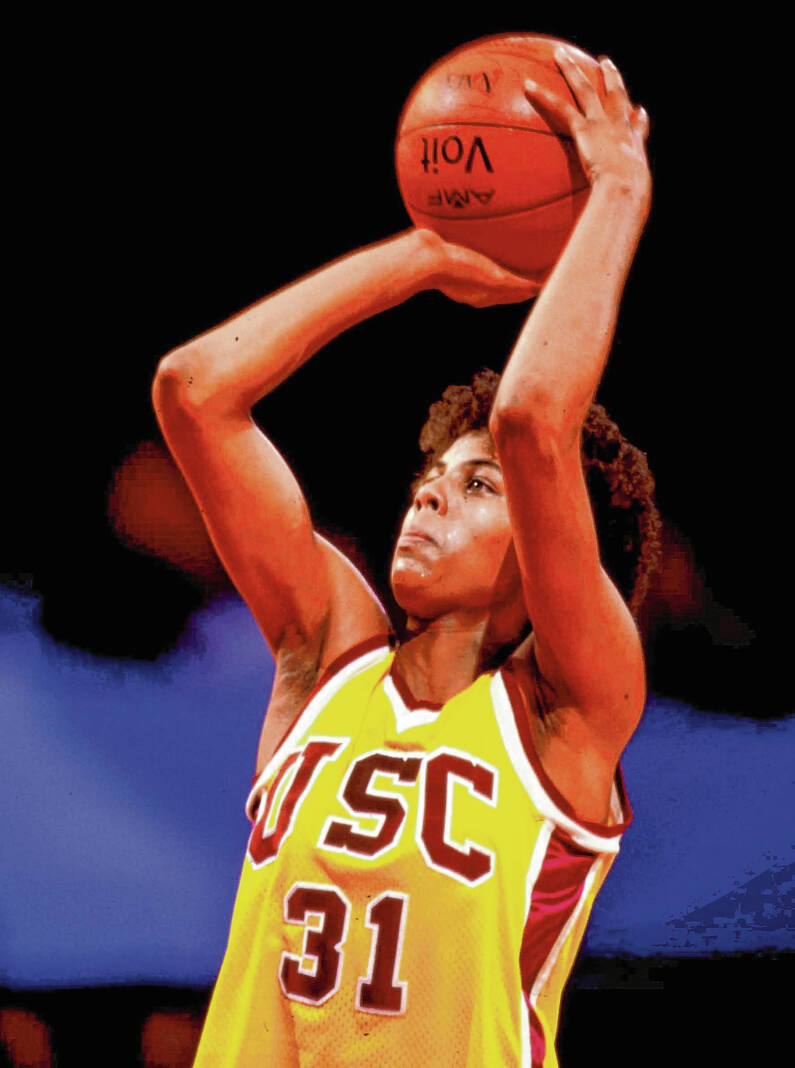

Cheryl Miller was acclaimed as perhaps the best player ever when she competed for the University of Southern California in the 1980s.

University of Southern California Athletic Department photo

Cheryl, Miller, the older sister of former Pacers great Reggie Miller used to play backyard ball with him in California before she became touted as one of the finest female players ever.

University of Southern California Athletic Department photo

(From the college level to the pros, in Indiana, with Seymour women playing crucial roles, and around the nation, in person and on television, women’s basketball is reaching unprecedented heights of popularity propelled by Caitlin Clark and other new faces. The Tribune examines the developments in a four-part series.)

When Teri Moren was a little girl growing up in Seymour in the early 1980s, she was a street rat as much as a gym rat long before starring for the Owls’ girls team.

She played basketball until the sun went down on outdoor driveway hoops. When she adjourned indoors to watch sports on television, however, her channel clicker never found women playing basketball on the tube.

Nowadays, everyone from the casual fan to Indiana expatriates can watch women’s basketball just about anywhere, through accessing the Big Ten Network, to nationally televised college games, on livestreaming services of all types, and through expanded WNBA TV coverage.

This school year, 2023-24, the compelling achievements of high-scoring Caitlin Clark of Iowa, as she led the nation’s women in scoring and broke all-time records for men and women with her statistics, as well as enrapturing fans because of her long-distance shooting, created new viewers and drove ticket sales at many venues.

At least once this past season, Moren, now 55 and 10 years into coaching IU, referred to “The Caitlin Clark Effect,” which became a trendy online phrase, giving props to a league opponent the Hoosiers faces regularly.

Katherine Benter, 21, the former Brownstown Central star who plays guard for Hanover College, lived through the opposite experience from young Moren this past winter.

Benter said she saw more women’s college basketball on TV last season than “in my entire life.”

The hullabaloo surrounding Clark was extraordinary in degree for a woman’s basketball player, but one side effect of this effect was reminding people of the stars who came before.

When Title IX was approved in 1972, there was a growing clamor for colleges to field women’s basketball teams and the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women filled the need because the NCAA was not interested.

Between 1972 and 1982, when the NCAA did start its own women’s hoop tournament, some then-famous teams won titles featuring historically memorable players, many since overshadowed except in the minds of historians.

Among teams making a mark were Immaculata College, Delta State, Queens College, Old Dominion and Louisiana Tech, with Tennessee coming up on the outside and under the late coach Pat Summitt.

Between 1974 and 2012, Summitt won 1,098 games and eight NCAA titles, leading to a compelling rivalry with Connecticut’s Geno Auriema, whose teams have won 1,213 games and 11 national crowns.

It was Summitt, whom Moren’s mother Barbara told her to emulate because she was a strong woman and a good leader. Summitt was also a favorite of Donna Sullivan, Moren’s high school coach at Seymour and currently president of the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame.

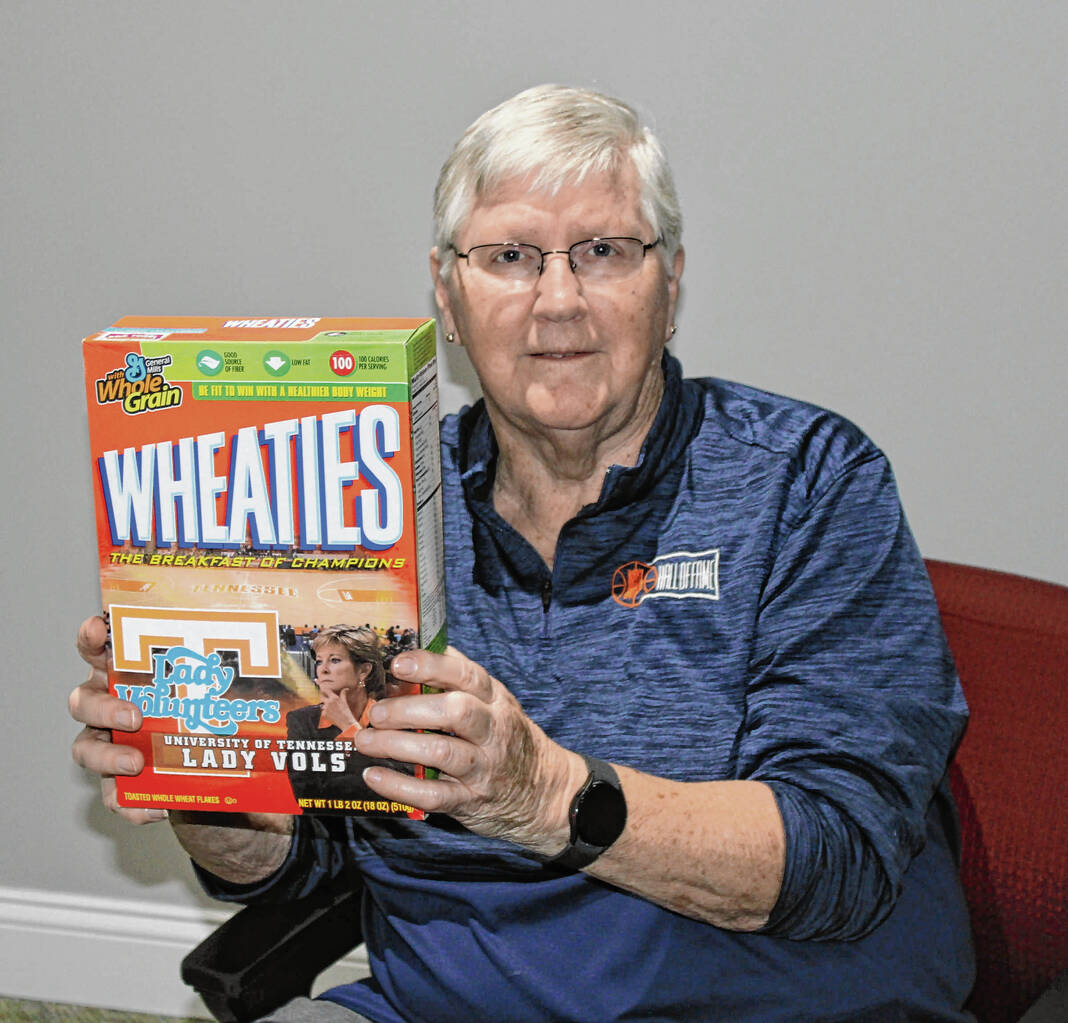

Sullivan owns a Wheaties box with Summitt portrayed on it as part of her memorabilia collection. Also, through coaches’ association meetings, and sometimes as Summitt’s driver at events, Sullivan got to know the woman.

“She was the female coach everyone identified with,” Sullivan said.

Sulivan has intensely followed the women’s NCAA tournament’s growth, attending in-person all over the country since 1988 with the exception of two years – basically seeing Summitt win all of her championships.

Tiny Immaculata, on the outskirts of Philadelphia, was on the verge of bankruptcy when the nuns who operated the religious school backed the idea of starting a team.

To everyone’s shock, the Macs became wildly successful under a former high school coach named Cathy Rush. Immaculata won the first three AIAW championships in 1972, 1973 and 1974 and finished second two straight years after that.

Nicknamed “The Mighty Macs,” among the standouts were Rene Portland, who later coached Penn State, Theresa Shank Grentz, and Marianne Crawford Stanley.

Stanley was a point guard who soon after graduation coached the legendary Old Dominion title teams with Nancy Lieberman, called “Lady Magic” (in deference to Magic Johnson) and Anne Donovan, who later coached the WNBA’s Indiana Fever.

Just two years ago Marianne Stanley, who also coached the Fever, was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

In the 1970s, there was little mainstream media coverage of women’s college basketball, not even a women’s top 25 poll.

That changed chiefly due to the energy and effort of the Philadelphia Inquirer. Far-seeing sports editor Jay Searcy approached staff writer Mel Greenberg in 1975 and assigned him to start a women’s weekly rating system. Greenberg built the poll from non-existent to something the Associated Press took over and still operates.

Greenberg became an influential voice in the women’s game with his writing and ideas, was awarded a special media award and then had the award named after him.

Greenberg, at 77, still writes on women’s basketball and serves on various support committees. His online handle is “WomhoopsGuru.”

“The Guru” also is his nickname among long-time women’s basketball followers who consider him a treasure. He was enshrined in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2007.

“I think you’re nuts,” Greenberg said in a recent interview about what he told the boss initially and how he doubted the success of early coverage.

Women’s basketball grew by milestone leaps.

“Every year the freshman class was better than the senior class,” Greenberg said.

Clark became a household name partially because she obtained national advertising sponsors. She benefited from college sports’ new Name, Image and Likeness payout policies, so her face was seen all over national television.

From the perspective of a half-century of observation, Greenberg won’t proclaim Clark the best-ever women’s basketball player based solely on statistics, though, he said, she does things “no one else has ever done.” Such as making shots 30 feet from the basket.

Playing too soon to become as widespread national figures as Clark, Lynette Woodard, out of Kansas, Donovan from Old Dominion, Cheryl Miller out of Southern Cal and Carol Blazejowski from Montclair State, can stake claims as defining players.

There are other women who go back to the beginning in of the W, some whose related work endures. Rebecca Lobo starred with University of Connecticut title teams, played in the WNBA and retains visibility as an announcer. Guard Teresa Weatherspoon of Louisiana Tech won two NCAA crowns, was a cornerstone W player, won multiple Olympic gold medals and now is coach of the Chicago Sky.

The best and most decorated Fever player since the franchise began in 2000 was Tamika Catchings, who later became the general manager.

Sullivan votes for Woodard, whose scoring numbers Clark passed this past season, and whom Sullivan just talked with at the recent Indiana hall women’s banquet in May, as best-ever.

“She was tremendous,” Sullivan said.

So good so long ago in college was Blazejowski, aka “The Blaze,” a 5-10 guard who played collegiately between 1974 and 1978. She averaged 38.6 points a game in 1976-77 and 31.7 for her career, without the three-point shot. Confident in her shooting, the Blaze wore a button on her warmups reading “BOSS.”

There was no women’s pro league for her in the United States, though much later Blazejowski became general manager of the New York Liberty in the WNBA.

“Blaze was the Caitlin Clark of her time,” Greenberg said.

Less publicized nationally than the men’s Great Alaska Shootout was the creation of the Northern Lights Invitational in Anchorage, Alaska, which had a impact for those in the know.

In 1978, the NCAA Division II University of Alaska Anchorage realized it could offer men’s Division I teams three exempt games that didn’t count against their schedule limits. That appeal brought seven big schools to the community each year.

Members of the UAA women’s basketball team protested, “What about us?” Three players sued for equal treatment under Title IX, one of them, Robin Greene, sticking out three seasons playing for the Seawolves.

Years later, Greene said she was proud to get involved in the fight, which was settled by consent decree. “You bet,” Greene said. “That’s something nobody can take away from me.”

The format of the complementary new Northern Lights Invitational called for UAA to host seven Division I schools and it was the only such tournament in the country. Everyone wanted to be part of it.

“The great teams all went there,” Sullivan recalled.

Tennessee’s Summit went north with such featured stars as Chamique Holdsclaw and Catchings. Cheryl Miller played in Anchorage. So did Weatherspoon.

Miller, who later coached USC to a national title, remains on the short list of nominees for best-ever woman’s player. Similarly to Clark, Miller was in constant demand for interviews and signed autographs for little girls. National player-of-the-year, NCAA champion, and Olympic gold-medal-winner, Miller played in the Northern Lights in 1986.

As a Southern California gal who played backyard ball with younger brother Reggie, Miller said she never thought she would play basketball in Alaska. Before she arrived, she said, “I’m prepared for the cold. I’ve got a coat.” Good thing, at that time, the tournament was held in February.

A Sports Illustrated basketball story suggested Miller transcended sports into the entertainment realm. Miller said you would never hear her say such a thing. But that was 38 years ago, a decade before the WNBA existed.

Eventually, as other tournaments were created, the men’s Shootout folded, the Northern Lights changed its name to Great Alaska Shootout, and shrunk to a four-team tournament.

The event is still very much a recruiting tool for coach Ryan McCarthy and the Division II powerhouse he has built. It is a lure for Division I teams to take an exotic road trip where athletes may take snowmobile or dog-sled rides and see a different part of the world.

“The tournament itself has a very good reputation,” McCarthy said in a recent interview. Last year, Utah, with All-American Alissa Pili, a first-round pick of the Minnesota Lynx, was an attraction, coming home to Anchorage to play.

This recent overall college basketball growth should help the tournament to stay strong, McCarthy thinks.

“I hope so,” he said. “There are generational talents in the sport,” he said.

Some of whom will no doubt have Alaska on their playing resume.