Dax Rosales, left, with the Jackson-Jennings Community Corrections Work Release Center and Levi Peacock with the Seymour Police Department participate in a role play scenario during Crisis Intervention Team training Sept. 22 at the Seymour Police Department.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

From left, Ryan Baker with the Seymour Police Department, Skylar Thompson with the Jackson County Sheriff’s Department and Chasity Gerkin with Jennings County Probation participate in a role play scenario during Crisis Intervention Team training Sept. 22 at the Seymour Police Department.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Megan Cherry, co-coordinator of the Jackson & Jennings Crisis Intervention Team, leads a session of CIT training Sept. 22 at the Seymour Police Department.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Lindsay Sarver with Healthy Jackson County, Sam Maxwell with the Jackson County Sheriff’s Department and Joe Madden with the Jackson-Jennings Community Corrections Work Release Center participate in a role play scenario during Crisis Intervention Team training Sept. 22 at the Seymour Police Department.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Dawn Goodman-Martin speaks during a session of the Crisis Intervention Team training Sept. 22 at the Seymour Police Department.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

From left, Dawn Goodman-Martin, Lindsay Sarver and Sam Maxwell debrief after a role play scenario during Crisis Intervention Team training Sept. 22 at the Seymour Police Department.

Zach Spicer | The Tribune

Participating in the first Crisis Intervention Team training for Jackson and Jennings counties were, front from left, Mark Corya, Emily Browne, Faith Heathcote, Michael Davisson, Crystal Schapson, Natasha Goins, Megan Cherry, Shana Richmond, Lindsay Sarver, Sarah Knoy, Dax Rosales and Dawn Goodman-Martin and back from left, Aaron Wilkins, Mark Holt, Carrie Tormoehlen, Amy Carroll, Sam Maxwell, Jalena Belding, Chasity Gerkin, Chris Everhart, Travis Shepherd, Skylar Thompson, Cory Walker and Josh Fleetwood.

Submitted photo

Seymour Police Department Sgt. Crystal Schapson is co-coordinator of the Jackson & Jennings Crisis Intervention Team.

Submitted photo

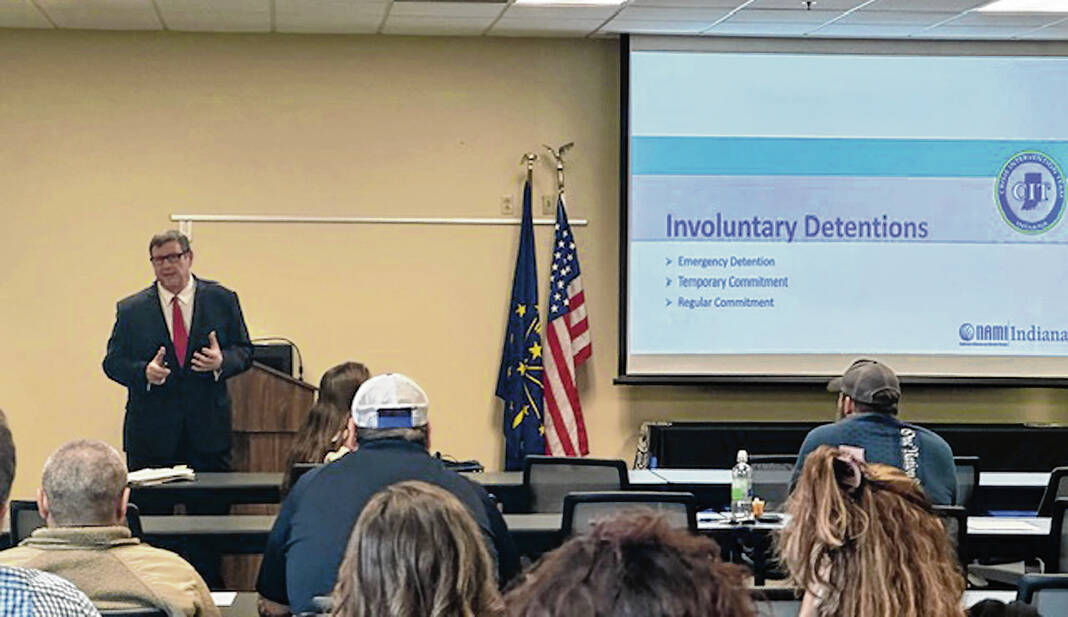

Jackson Superior Court II Judge Bruce MacTavish speaks to the participants of the Crisis Intervention Team training in September at the Seymour Police Department.

Submitted photo

Dr. Joyce Spurgeon with Schneck Mental Health & Wellness speaks to the participants of the Crisis Intervention Team training in September at the Seymour Police Department.

Submitted photo

Steve Hoffman, who retired from the Morgan County Sheriff’s Office, talks about first responder mental health during the Crisis Intervention Team training in September at the Seymour Police Department.

Submitted photo

Misty Hogan with Landmark Recovery shares her lived experience in recovery during the Crisis Intervention Team training in September at the Seymour Police Department.

Submitted photo

U.S. Army veteran Jason Truitt speaks during the Crisis Intervention Team training in September at the Seymour Police Department.

Submitted photo

Serving as executive director of Jackson County’s homeless shelter, it made sense for Megan Cherry to get involved in the Crisis Intervention Team steering committee.

Under the nonprofit corporation CIT International, the CIT program is a community partnership of law enforcement, mental health and addiction professionals, individuals who live with mental illness and/or addiction disorders, their families and other partners to improve community responses to mental health crises, according to citinternational.org.

Through her work with Anchor House Family Assistance Center and Pantry in Seymour, Cherry said mental health affects a big portion of the clients.

“Ever since opening the new facility (East Shelter), we’ve had a whole group of individuals that we weren’t previously able to serve, and it has brought about more challenges and resources that we haven’t had available,” she said, as they went from only serving homeless families with children to also helping individuals.

“It was important for me to figure out how we as Anchor House can best serve individuals with mental illness or substance use,” she said. “At the end of the day, that’s my goal is to just be an advocate for those I serve and just the community as a whole for anybody who is untreated and maybe so stigmatized that they haven’t been able to get the help they need yet, making it OK and bringing awareness to ‘Let’s get that. Let’s make that happen.’”

The steering committee operated under Mental Health America of Jackson County in 2021 and 2022.

After the local MHA chapter dissolved, Cherry assumed responsibility of the CIT in late 2022.

She was approached by Jennings Circuit Court Judge Murielle Bright to see if she could assist that county, too. It then became known as the Jackson & Jennings Crisis Intervention Team.

In February, Cherry completed the two-day training through CIT International to become a local certified coordinator. That certificate is good for three years.

“Once becoming involved in it and going through the training, mental health became a huge passion of mine because it touches so many lives — me personally and then I have a large amount of friends and family in the law enforcement community that are also touched by post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma,” she said. “It just became very important for me to bring mental health to the table for people to discuss.”

Then in August, she went through the 40-hour weeklong CIT training in Johnson County to become CIT certified.

The next week, she went to the CIT International conference in Detroit, Michigan, where people from all over the world came together to talk about what CIT looks in their communities.

That set her up for leading training for 22 law enforcement officers, 911 dispatchers and community corrections, probation and jail officials from Jackson and Jennings counties from Sept. 18 to 22 at the Seymour Police Department.

“When I took over, one of the main goals was to get the 40-hour training up and running in the community because that’s what certifies our first responders and police and all of that to be CIT officers,” Cherry said.

The training follows a very specific curriculum that has to be met per CIT International, she said.

“It’s just various topics regarding mental health in adults and youth, substance abuse. There’s a focus on PTSD, trauma-informed care, trust-based relationship intervention,” she said. “We explore traumatic brain injuries, and then we look at officer and first responder self-care and wellness.”

The training includes role plays and scenarios on certain situations with debriefing to follow, presenters from various entities and people with lived experiences of the topics.

Those who completed the course also are QPR certified after taking the Question, Persuade and Refer suicide prevention training, and they received a resource guide after hearing from a local resource panel from both counties.

Seymour Police Department Sgt. Crystal Schapson was brought on as co-coordinator of the local CIT because certain parts of the training have to be taught by or involve law enforcement.

Noticing the community and law enforcement agencies needed some type of crisis intervention, Schapson centered her trainings around it. She ultimately wants to be nationally Critical Incident Stress Management certified. But first, she took the CIT training in Johnson County.

After working in law enforcement for 17-plus years, she said repeated critical incidents take a toll on the mental health of first responders.

“I am not one to shy away from this topic and will be open in sharing how my own mental health had deteriorated over the years,” Schapson said. “There was little to no information on resources available for myself or any other first responder, and some of the systems in place would not be reasonable for various reasons.”

As mental health continues to be a topic in the forefront of many conversations, she said it’s still somewhat of a taboo conversation when it comes to first responders.

“If the mental health of our first responders is not discussed, addressed and positively sustained, we cannot adequately help someone in the community who may be suffering from a mental health crisis,” she said.

Helping teach parts of the first CIT training locally, Schapson said it opened the door to many conversations across the board about the resources available in the area.

“Megan and I received great feedback about class participants not realizing certain resources, even though they may drive by the buildings/offices every day,” she said. “It also gives the officers a better understanding of how they can assist someone in a mental health crisis, rather than having the situation escalate to the point where the individual goes to jail, force may be used and no actual helpful direction is given or offered.”

If first responders aren’t knowledgeable about the resources the counties provide, how can they expect citizens to have the same knowledge, she said.

“We could potentially lower call volume and recidivism rates by simply helping individuals in crisis to get the mental health treatment they need,” Schapson said. “By being knowledgeable about the resources, we can potentially open the door for the person to receive the treatment, therapy, medications, etc. needed rather than a continuous revolving door of being on the streets, then in and out of jail.”

There will be two sessions of CIT training in 2024: April 1 to 5 and Sept. 23 to 27.

Cherry said participants in the first training valued the lived experiences, so the plan is to have more of that in the next two sessions. They also were really passionate about the PTSD training and self-care.

Cherry said several law enforcement agencies in Indiana make the training mandatory, and she hopes that happens in Jackson and Jennings counties.

“Through a training, if we have one person that determines that their mental health is a priority or one department that determines the mental health of their officers or first responders is a priority, then it was worth all 40 hours,” she said. “CIT is one of those things you never want to have to use, but it’s nice to have in your tool belt for when you need it. It affects everybody.”

The next goal of the local steering committee, which consists of about 20 people, is to establish a CIT team that can break into specialized areas to be a resource to the community and be available 24/7 to first responders who encounter a crisis.

“They either work in mental illness or substance abuse or they have family or friends that are connected, and so they are passionate about the cause and making sure the CIT moves forward in the community,” Cherry said.

Another goal is to create a regionwide support system for first responders.

“We can have this peer support within first responders that if there is a critical incident somewhere, that team can be a part of helping them debrief and get any kind of help they need for their own mental health and trauma they are exposed to,” Cherry said. “We just really need to reduce the stigma around a mental health crisis and mental health in general and know that it’s OK to not be OK, but then how do we help you get to the other side of that.”