A great blue heron soaks up the sunshine while perched on a fallen tree branch along the White River in southern Indiana.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

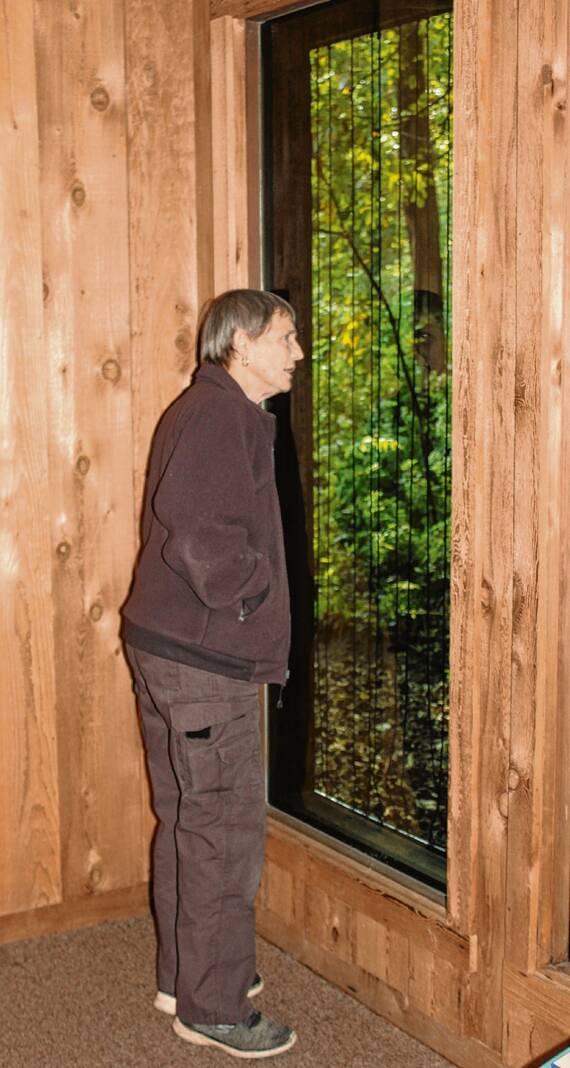

Ranger Donna Stanley watches for birds inside the Bird Room inside the visitors center at Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge. The room allows visitors to the refuge watch birds fly around the trees and eat at feeders.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

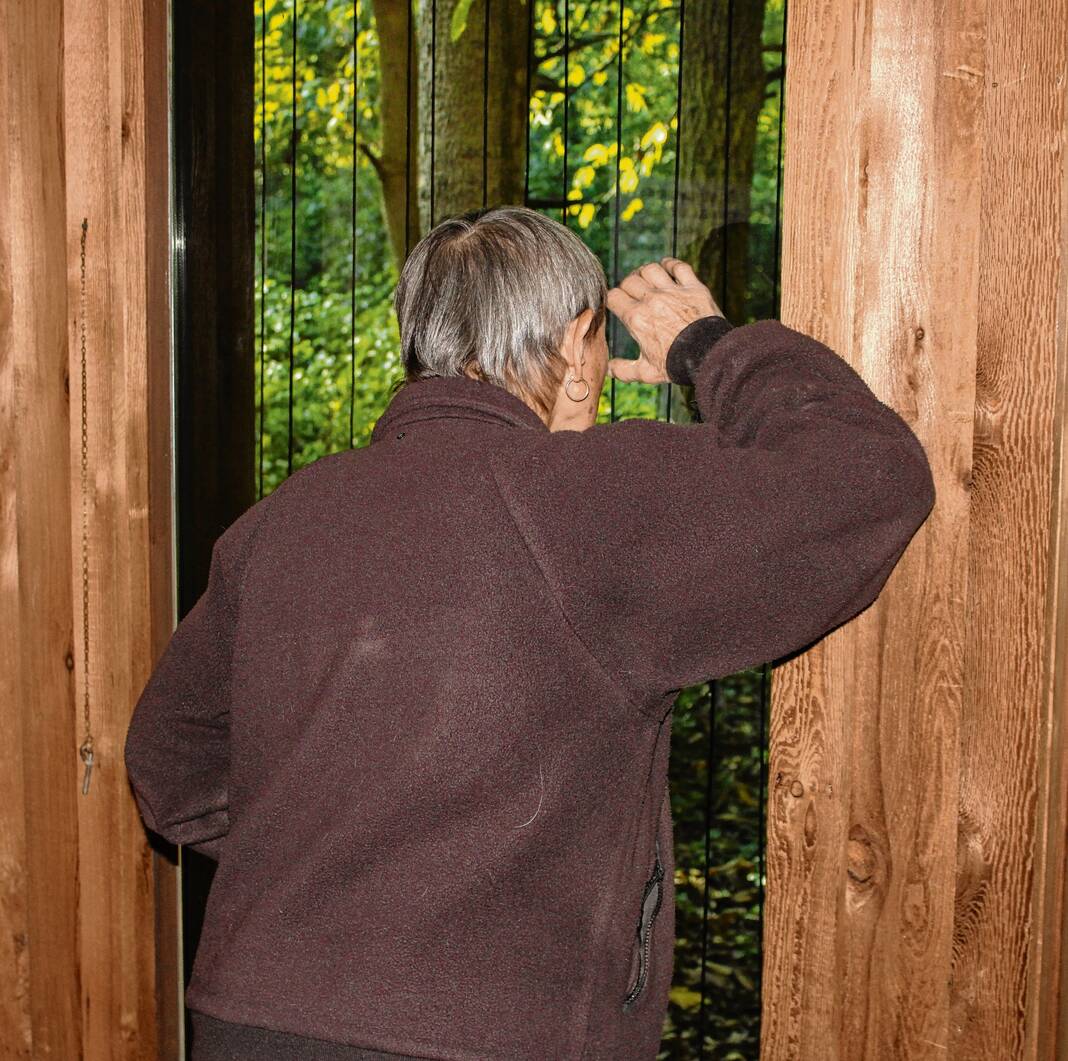

Ranger Donna Stanley watches for birds inside the Bird Room inside the visitors center at Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge. The room allows visitors to the refuge watch birds fly around the trees and eat at feeders.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

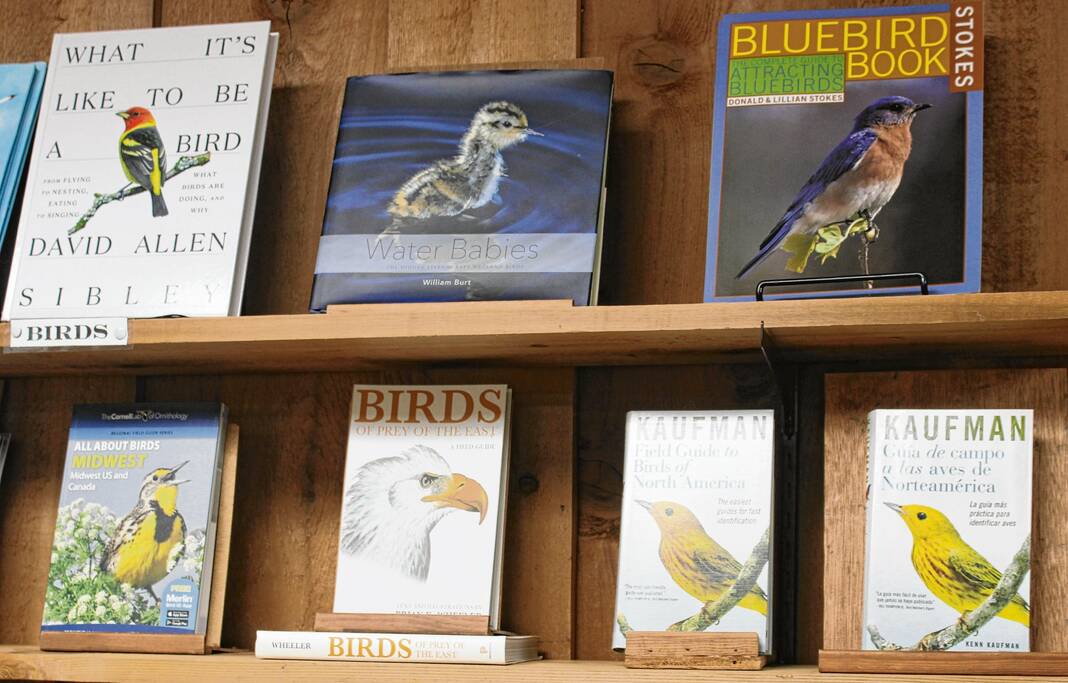

There are many guidebooks available for beginning birders including some sold at the Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge gift shop inside the visitors center.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

This sign marks the beginning of a hiking trail through the woods by the Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge visitors center, a short walk where typically many birds can be seen or heard.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

A group of Canada geese at Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge.

Lew Freedman | The Tribune

This bright blue bird that frequent Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge is an indigo bunting.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

The bright red cardinal is the Indiana state bird and are regularly seen at Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge, often flying in for refreshments at the bird feeder outside the Bird Room at the visitors center.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

The background music of America is the songbird, birds of many colors and many tunes providing a never-ending series of concerts projected from treetops or fast-flying fauna fluttering past.

Most are soothing sounds, or ear-catching ones, whether people are savvy enough to recognize the calls or not. Until humans usurped the word with the invention of X, formerly known as Twitter, they used to be summed up as tweets.

The sight and sounds of birds almost universally fill people with pleasure. Millions describe themselves as birdwatchers, vicarious participants in nature, spotters who consider birding sport, a challenge or a simple joy.

“Birds are really important to people,” said Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge ranger Donna Stanley. “They’re so interesting and so important to the ecosystem.”

New birders now come to the activity at a time when there is scientific concern over that ecosystem and the diminishment of the number of birds in the skies, when the character of the most famous birder in history is being re-evaluated, and there are also more technological aids available to woo birders into the nest.

Nine-hundred-page books can be encapsulated on phones and play back sounds for study. An international website, eBird, can tip off birders where to go for fresh sightings.

These state-of-the-art electronics draw the birding community tighter. State ornithologist Allisyn-Marie Gillet was a longtime holdout lugging bulky guide books into the woods and only recently purchased a bird identification app on her phone for around $25.

“I sucked it up,” she said. “I can’t believe how much lighter it is.”

Birdwatching is a widely encompassing term. Anyone can do it by keeping eyes and ears open. The range of commitment can be compared to long-distance running. There are Olympic marathoners and those who jog around the block.

Unlike other sports or activities which may demand a person have fully functioning knees or a certain level of stamina, birdwatching has become a popular hobby for people of retirement age with more free time.

“You can get started watching a bird feeder in the backyard,” said Whitney Yoerger, communications manager of the Indiana Audubon Society.

People contact the Connersville-based state Audubon Society for advice regularly, said Yoerger, who describes herself this way: “I’m an adult-onset birder.”

Gillet, who works for the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, said a birdwatcher need not shell out for expensive equipment like a hockey goalie but suggested buying binoculars and a guide book or phone app for identifications.

“If you’re really committed, invest in a good pair of binoculars,” she said. “That’s really, really important for this hobby. A mentor is also really important. They can tell you where and when to go someplace, what to look for and what to listen to.”

Birders often maintain life lists keeping track of the species they see, by happenstance or by traveling the planet. Financial considerations and time limits help individuals determine how much is enough and how much is too much.

There is plenty to see and hear. The Audubon Society, the state DNR and the website eBird agree 422 bird species have been reported in Indiana. There are, however, approximately 11,000 different species of birds inhabiting Earth.

Muscatatuck refuge

It is perpetual dusk in the Bird Room inside the visitors center at Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge in Seymour. People sit on benches staring through tinted windows as birds fly in to grab food from outdoor feeders. Or they stand next to the glass, shade their eyes and peer out.

Nearly 300 species of birds may annually pass through Muscatatuck. The Bird Room, used since the 1990s, brings nature close, especially for those with limited mobility who can’t hike the refuge’s 7,724 acres or maneuver in wheelchairs.

“It is accessible,” Stanley said. “Lots of people come and just sit here and watch the birds.”

Prime time is winter, Stanley said, when 100 species may be viewed in the refuge. The total may range from 60 to 100 in spring. The cardinal, living up to its responsibility as the official state bird, often appears.

The northern cardinal has been Indiana’s state bird since 1933. It is also the state bird of six other states. Kentucky anointed the cardinal king of its birds in 1926, and Illinois did so in 1929.

“Cardinals are beautiful,” Stanley said of the bright red male. “And they are more visible than most other bird species and animal species. People like cardinals.”

Stanley plugged indigo buntings and their equal brightness in blue as another bird worth seeing.

“They’re like pieces of crystal flying,” she said.

Muscatatuck provides a brochure printed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a visitor checklist categorizing birds likely to be seen at the refuge.

The list is long, with such birds mentioned as common loons, great blue herons, turkey vultures, snow geese, mourning doves, barn owls, red-headed woodpeckers, bald eagles, red-tailed hawks and peregrine falcons.

The Bird Room is an amenity of convenience and so is the feeding yard.

“Birds don’t really need bird seed,” said Stanley, who calls herself “a mediocre birder.” “(Bird seed) doesn’t hurt them. It does attract them so people can see them up close.”

David Crouch, 78, of Seymour did not start birdwatching until retirement and began working at the refuge in 2006. Crouch’s life list is 573 birds, but he and wife Sally have not gone to the ends of the earth for birds. They have driven outside the state, though, and own one car they call “the birdmobile.”

Crouch said he gets gratification from introducing young people to birding.

“I really, really enjoy getting youngsters turned on to it,” he said, “getting kids outdoors and interacting with the natural world.”

Birds may swoop into the backyard and partake of goodies in a feeder, can be spied flying overhead through binoculars, but some birds are only heard and ID’d by their songs.

The recent advent of bird phone apps has been a major development. There are numerous lengthy and reliable bird field guidebooks, such as Sibley’s, Kaufman’s and Peterson’s.

Yet apps can supplement photographs with song. The famous Cornell University Ornithology Laboratory put out Merlin, a free app.

“I find that sound to me is kind of easier,” Gillet said. “It takes a lot more time to look at them than to hear them.”

TYoerger said she tapes birds to learn their calls later. Generally, she said, recordings are “only as good as the user. ‘Was that a great blue heron or was it my dog barking?’” she said.

Yoerger said her favorite bird is a chimney swift. She called them “amazing birds.” Chimney swifts mate for life and are incapable of perching on branches and must vertically cling to trees.

One recent morning at Muscatatuck, Susan Miller of Columbus, who has led bird hikes at the refuge, heard a bird sound she did not recognize. Miller whipped out her cellphone and began exploring. She quickly heard a half-dozen possible options. Then her phone rang, interrupting. No, it was not a bird calling with the right answer.

Miller has simple bird beginner advice.

“Watch for movement,” she said. “If you see anything out of the ordinary, you might want to focus on that. If you see a white blob in the trees, it might be a hawk.”

She counsels birding patience.

“Just look at it as going out and enjoying nature with birds being a benefit,” she said.

Shrinking numbers

Researchers at the University of New South Wales in Australia suggest there are between 50 billion and 428 billion birds in the world. In 2021, a different study indicated there were about 3 billion fewer among 303 species than in 1970.

That report set off alarms, blaming climate change, pollution and habitat loss. Migratory birds traveling thousands of miles between countries seemed in particular danger.

“It’s a big deal,” Gillet said. “The migratory journey is one of the riskiest parts of their lives.”

The news spawned “a new initiative” by a group of American and Canadian scientists called Road to Recovery: Saving Our Shared Birds. Nonprofit organizations and state agencies are banding together to reverse the trend, she said.

Yoerger said the accounts about billions of birds vanishing struck hard.

“Birds are definitely having a struggle right now,” she said. “There is a dire need for people to care about birds right now.”

Also occurring — and this is a months-old development and probably surprising to laymen — groups with the words “Audubon Society” in titles are re-evaluating their relationship with the godfather of American birds.

For roughly 200 years, John James Audubon has been the exemplar of the bird world. Between 1827 and 1839, Audubon brilliantly painted every species of bird he could, identified 25 new species and produced an extraordinarily admired book called “The Birds of America.” Only 200 copies were made, and just about 120 survive, mostly in museums and libraries. Though reprints are affordable to the masses, in 2018, one original copy was auctioned for $9.65 million.

The Indiana Audubon Society was founded in 1898. In a bow to Audubon’s stature, numerous regional, state and local Audubon societies spread throughout the country using his name. Recently, closer examination of the man has provoked controversy.

Audubon raised money to support his work by buying and selling slaves. A few months ago, the New York City Audubon Society dropped his name. So did Maryland. Despite intense debate and the resignation of some board members, the National Audubon Society voted to keep “Audubon” in its name but said, “We must reckon with the racist legacy.”

The Indiana society is examining the issue. Yoerger called the review “an important avenue for the self-reflection and evolution” that is part of “a larger dialogue about diversity, representation and equity in the conservation community.”

Yoerger emphasized the organization supports bird watchers of all stripes, colors and human species.

Birds everywhere

Within the birding fraternity an online fount of information “eBird” is well-known. A section under eBird Indiana allows posting the name of a bird sighted, the date, the name of the “observer” and the location. Rather than scribbling in private notebooks as used to be routine, people can record sightings for everyone to read.

Gary Dorman of New Albany, a 49-year birder who has participated in the annual Christmas bird count at Muscatatuck 35 times, said he believes eBird has had 2 billion posts.

Dorman, who proposed to his wife, Becky, while birdwatching four decades ago, has a life list of 561 birds. He and other Hoosiers were enthralled by the presence of a flamingo seen in Patriot, 79 miles from Seymour, in September. The flamingo was blown north by Florida hurricane winds. Birders flocked to Patriot and recorded flamingo sightings on eBird.

“The flamingo was huge,” Dorman said.

Birdwatchers can be bird chasers, as demonstrated in the classic book “The Big Year” or seen in the movie starring Steve Martin, Owen Wilson and Jack Black played men racing to see as many birds possible in a calendar year. This true story illustrates how birding can become an obsession and take over one’s life, especially if the bank account is fat enough.

“It’s certainly eccentric,” Crouch said.

Eagles rule

For all of those thousands of birds across the world and the hundreds in Indiana, the bald eagle still seems to resonate most with Americans. The United States’ national bird since 1782 was once threatened with extinction but is one of the country’s great conservation stories.

One lasting Crouch memory was seeing an adult bald eagle perched in a tree at Richart Lake at Muscatatuck dive down and steal a large fish from an otter.

There are regular bald eagle postings on eBird Indiana, but often, when someone seems an eagle in the wild, in nature in Indiana, they feel motivated to telephone ornithologist Gillet to let her know personally.

“They love calling me about a bald eagle,” she said. “To them, that is important.”