Seymour High School’s first girls basketball uniforms were T-shirts and shorts purchased off of the rack at K-Mart or Penney’s.

A laundry dyed them purple, and the numbers were ironed on.

As rudimentary as it got 50 years ago, no one cared about style, only opportunity.

“We were just excited to play,” said Alice Laskowski, a member of Seymour’s original girls basketball team. “We thought it was the greatest thing that ever came along.”

When she was a teenage high school student, Laskowski didn’t really know the hows or whys of it, the politics and could not foresee the sea change arriving, but in a much bigger sense, she was right. For girls and women in high school and college sports, Title IX was the greatest thing that ever came along.

Laskowski, now 68, didn’t recognize it, but she and her sister Lady Owls were as much pioneers as the women who rode in covered wagons across the prairie to settle the West.

Once patronized as “the fair sex,” labeled unladylike if they dared sweat on a sporting field and told they lack the necessary stamina to compete in sports, American females of Laskowski’s generation helped usher in a new age and societal outlook under the auspices of federal government legislation enacted in 1972.

Their mothers and grandmothers had limited options to compete in organized sports, often shut out of playing beyond gym class, and college athletic scholarships for women were virtually nonexistent.

In contrast, now, sports fans can flip on the TV and watch women’s college basketball, volleyball, soccer almost at will, a 50-year journey jump-started and shepherded by Title IX.

Only those of a certain age and a sense of history are aware of the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, the six-player form of basketball or the Billie Jean King-Bobby Riggs hyped tennis match.

In 1971, the year prior to the enactment of Title IX, there were 295,000 girls playing high school varsity sports in the United States, already representing an upswing over the past. As of the fall of 2022, there were 3.24 million.

Those first Seymour players never imagined there would be such growth in participation.

“We’ve come such a long way,” said Jean Laupus, 68, a basketball teammate of Laskowski at Seymour High School.

Equality for all

Title IX is about equal rights. It was not introduced and approved by Congress so more girls could dribble basketballs, hit softballs or spike volleyballs.

It is a federal civil rights law that amended the Higher Education Act of 1972, partially guided by then-Indiana Sen. Birch Bayh. Another champion, Rep. Patsy Mink, was motivated because only 42% of college students were women.

Signed into law by President Richard Nixon, Title IX reads: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of or be subjected to the discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

Intended as an expansion of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, closing a gap protecting employment in educational institutions, Title IX has basically been known as a sports law.

On the college level, the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women was formed in 1971 when there was no NCAA women’s sports authority and supervised a national basketball championship tournament through 1982.

Tiny Immaculata, a Roman Catholic college near Philadelphia, won the first three AIAW crowns. One player was Marianne Stanley, most recently head coach of the WNBA’s Indiana Fever. Some legendary women’s players competed in the AIAW, including Luisa Harris for two-time champ Delta State and Nancy Lieberman and Anne Donovan for two-time champ Old Dominion, coached by Stanley.

All have been inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. A documentary about Harris won an Academy Award.

Under Title IX, college athletic directors were required to equalize scholarships. Matching football and men’s ice hockey presented challenges.

Attitude, however, also played a role in defining equality. In many places, men’s college teams had four-star locker rooms, while women changed in lower-class facilities. Men flew to away games, while women’s teams traveled by bus. Men’s teams received new uniforms more often. It took lawsuits from female athletes at individual colleges to force compliance.

As recently as 2021 when the NCAA conducted its March Madness men’s and women’s basketball tournaments in “bubble” environments, the men in Indiana, the women in San Antonio, there was an outcry over unequal treatment for women, from an inferior weight room to not staffing early round games with photographers to less-reliable COVID-19 tests.

While the NCAA contributes millions of dollars annually to men’s conferences based on men’s team victories in the tournament, it had never given cash based on women’s wins.

This illustrated how slow some things were to change, but an illustration of how things were was the Houston Billie Jean King-Bobby Riggs “Battle of the Sexes” exhibition tennis match in 1973.

Riggs, once a highly ranked men’s player, at 55 was long retired. Riggs was a hustler, gambler, an overt male chauvinist and a showman. King, a many-time major champion who for years led the fight for equal pay for women on the circuit, declined to play him. Then Riggs beat top-ranked Margaret Court.

Juicing the gate and fanning publicity flames, Riggs said, “Women play about 25% as good as men, so they should get about 25% of the money men get.” Also, “Women belong in the bedroom and the kitchen in that order.” King called Riggs “a creep.”

King won the match 6-4, 6-3, 6-3 and said, “I thought it would set us back 50 years if I didn’t win that match.”

This nationally televised commotion had nothing to do with Title IX — and everything. Just as King, a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her work for women’s rights and in defending lesbian and gay rights, never should have been placed on the spot to defend all women. The nation arguably should never have needed the push to provide equality.

Yet, the United States with its Declaration of Independence and its Bill of Rights had always required a nudge to provide equal rights to minorities.

“In race, we still have a long way to go,” said Jane Emkes, a Seymour High School player who graduated in 1979, played at Ball State University and is in the Indiana High School Basketball Hall of Fame. “There’s no excuses for it.”

Lady Owls

Donna Sullivan is the godmother of Seymour High School girls basketball. Other sports, too.

Sullivan, 74, currently an assistant coach for the girls hoops program at Trinity Lutheran High School, played volleyball, field hockey and softball for Indiana University between 1966 and 1970.

“I couldn’t play high school basketball,” she said.

Because there was no girls school team. Instead, there was an organization called Indiana Girls Athletic Association, which did provide competitive outlets for girls.

Sullivan started the program at Seymour, pulled together those inaugural uniforms and coached at the school for 31 years. She is a member of the Indiana High School Basketball Hall of Fame, currently chairing a committee making recommendations to expand the women’s section next year.

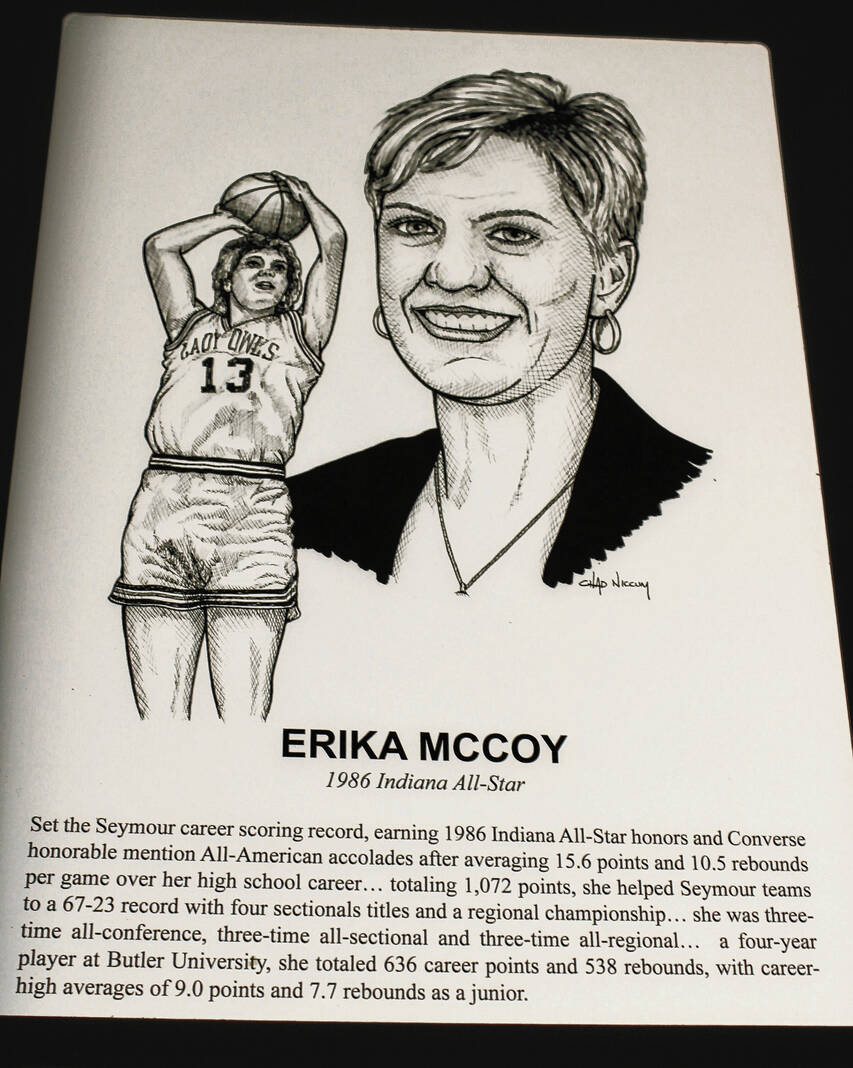

The Hall of Fame’s Seymour High School women’s basketball connections are Sullivan and players Laskowski, Erika McCoy, Emkes, Julie VonDielingen Shelton and Teri Moren, the current Indiana University women’s coach.

Emkes, 61, said in the late 1970s, the girls at Seymour practiced often in a little secondary gym and at 6 a.m.

“I didn’t think that was fair,” Emkes said.

But she was more conscious of unequal treatment at Ball State.

“The disparity was tremendous,” she said. “It didn’t feel like Title IX had made a thorough difference yet. To me, it feels like the last few years, especially with social media bringing attention, there is a difference. It has been 50 years, and I kind of feel we’re only just now getting there.”

McCoy, 54, who played for Butler after graduating Seymour in 1986, said there seemed to be great backing for the girls in Seymour. At Butler, the men got newer uniforms.

“Did I like it? No. Did I let it bother me? No,” she said. “The facilities are amazing now. I feel like, honestly, right now is a great time for women’s sports compared to before when I was involved.”

Laskowski, whose husband John played basketball for IU and in the NBA, worked for the Indiana Pacers for 25 years. Her father was the late Lloyd “Barney” Scott, former Seymour athletic director and the man for whom the local gym is named.

It was on Scott’s watch Sullivan was handed keys to the previous gym and given the directive to start a girls sports program.

Alice’s earliest sports competition was in middle school gym class, and she wanted more. She said Scott read the stirring winds.

“My dad kept saying, ‘You’ll get there someday,’” Laskowski said. “Donna Sullivan told us, ‘You guys are the beginning.’”

Laskowski marvels at changes she has seen in women’s sports. Although salaries remain an issue, players have a WNBA, begun after the 1996 Olympic team played together for a year, finished 60-0 and won a gold medal.

Pro ball? This once would have been inconceivable to Sullivan, Laskowski and Laupus, who lived through the era of six-to-a-side basketball.

For decades, most girls basketball was played as an alien form of the sport. There were six girls per team on the court at the same time, and only three could cross half-court. The other three players had to remain in the backcourt. In some quarters, this style was called by the feminine-sounding “basquette.”

“I hated the six-player game,” Sullivan said.

The average young basketball player today, male or female, doesn’t even know such a form of the sport existed. Oklahoma conducted the last school six-on-six games in 1995. Six-on-six was played in Iowa until 1993, a place where it was wildly popular. There is still a Granny Basketball League in Iowa for players 50-and-over where the women wear 1920s-style uniforms.

Laskowski and Laupus both made the transition from six-player to regular basketball under Sullivan at Seymour.

“It was such a different game,” Laupus said.

The origin of the six-player game was chauvinism. The societal image that it was wrong for girls to sweat in public and the belief they were not strong enough to keep running up and down the whole court prevented girls from playing five-on-five.

“Girls were not allowed to get stinky,” Laupus said. “That would definitely be unladylike.”

Once, the Laskowskis were sitting around the house talking basketball with their four kids. John said, “Your mother was a good basketball player.” When he mentioned the six-person game, they went, “What?”

They found the idea so crazy the whole clan decamped to a gym where Alice arranged the players on the court in six-player formation.

“When I look back at that,” she said, “whatever made them think we wouldn’t have the stamina?”

Remembering history

Last summer, Sullivan was riding on a bus with the Trinity Lutheran girls to an event at West Washington, and seized by the awareness that Title IX’s golden anniversary was approaching, she spontaneously asked a question.

“How many of you know what Title IX is?” she said. Some hands went up. “How many of you know what Title IX does?” Fewer hands went up.

A classroom lesson on wheels followed.

“You’re playing today because of it,” Sullivan said. “Go home and thank your great-grandma.”