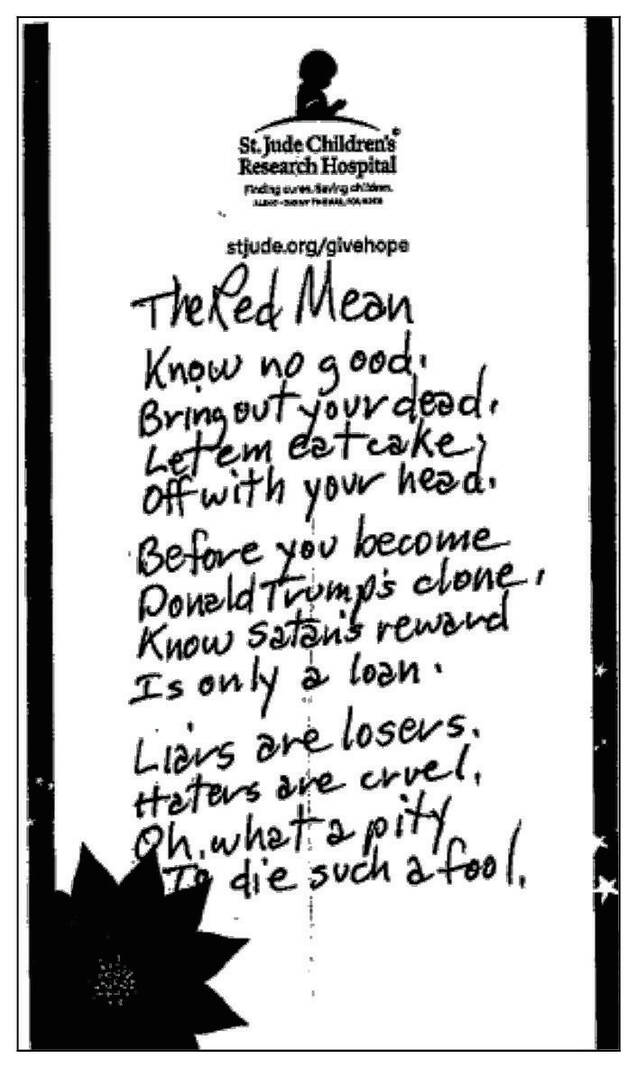

A screenshot of the poem that resulted in a federal lawsuit over a Jackson County Public Library patron being banned for life from the facility.

Submitted photo

By Andy East | Aim Media Indiana

A federal judge has ruled that the Jackson County Public Library’s decision to ban a patron for life over a poem he wrote and dropped off at the library critical of former President Donald Trump was unconstitutional.

In a decision filed in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana on March 31, Chief Judge Tanya Walton Pratt found the library “violated and is violating” a Jackson County man’s rights under the First and 14th amendments by permanently banning him “for exercising protected speech.”

The lawsuit, filed in January 2021, stems from an incident that occurred Nov. 16, 2020, when plaintiff Richard England, 68, visited the Seymour Library to return several items and check out some DVDs, according to court records.

That day, England also brought an original poem he had composed, titled “The Red Mean,” which he intended to give to a library employee “with whom he was friendly.”

The employee, however, was not there at that time. As a result, England decided to leave the poem in a basket on the circulation desk, which contained medical face masks for library patrons, and then left the library without incident.

The poem reads: “Know no good, bring out your dead, let them eat cake, off with your head. Before you become Donald Trump’s clone, know Satan’s reward, is only a loan. Liars are losers, haters are cruel, oh what a pity, to die such a fool.”

England claimed in court filings he had written the poem to “express (his) belief that the politicization of the COVID-19 pandemic by then-President Trump and his followers, including their apparent opposition to rudimentary safety measures … was leading and would continue to lead to the unnecessary loss of life.”

The title of the poem was a reference to “the character of ‘the Red Queen’ in ‘Alice in Wonderland,’” England said.

But library staff had a very different interpretation of the poem, court records show.

About 15 to 30 minutes after England left, a library employee found the poem inside the basket while providing a mask to a patron. The employee “was scared after reading the poem” and believed it contained threatening language, “particularly its references to death and Satan.”

The employee then gave the poem to her supervisor, who “was shocked, scared and confused.” The supervisor then gave the poem to the library administrator, who said when she spoke to staff, “(their) voices were shaking. They were really upset.”

“This fear was enhanced by the political climate surrounding the 2020 election and anxiety surrounding the pandemic,” the library contended in court filings.

The poem was unsigned, but staff determined England had put it in the basket after reviewing video surveillance footage.

When England returned home, there was a voicemail waiting for him from a Seymour police officer, who informed him he was “banned from the library for the rest of his life, and that if he returned to the library, he would be arrested for criminal trespass.”

England then went to the Seymour Police Department and spoke with the officer who left the voicemail, who informed him again of the ban and trespass order.

England returned home again and called the library and spoke with the circulation manager, who said, “We don’t do politics at the library.”

“The circulation manager reiterated to Mr. England that he was banned from the library and that library staff had already spoken with the library’s attorney and been assured that they could take this action against him,” according to court records.

About four months later, England filed a lawsuit in federal court, seeking an injunction to bar the library from enforcing the ban and requiring the library to reinstate his library privileges as well as attorney fees and court costs. England moved for summary judgment April 14.

The Jackson County Public Library, for its part, has claimed it was justified in banning England, moving for summary judgment May 12.

More specifically, the library argued in court filings that the poem violated library policies on “threatening or obscene language” and threatening behavior. The library also argued England’s conduct violated health protocols because he had placed the poem in a box of sanitary masks, as “with COVID you don’t know what is on anyone’s hands.”

The library further argued the ban was not motivated by England’s political views but rather what staff perceived as “the threatening nature of England’s poem.”

Additionally, England was previously known to library staff for having “very decided views on politics” and was “known to become agitated when he shared those views with other employees,” court records state.

“This agitation would also result in England speaking loudly,” the library alleged in court filings. “This agitation was known to be disruptive in the area around the information desk.”

In 2018, England was fined $5 for allegedly defacing a DVD cover by writing “Sick propaganda. A curse be upon this lie. May you suffer the truth!” Library staff allegedly warned England at that time he would be permanently banned if it happened again.

But Walton Pratt sided with England, finding that poem was “political hyperbole,” which is protected speech under the First Amendment.

In her decision, Walton Pratt cited, among other things, the 1969 U.S. Supreme Court case Watts v. United States. In that case, the Supreme Court overturned a lower court’s decision that an 18-year-old Black man who was protesting the Vietnam War and military draft had committed a felony for threatening then-President Lyndon Johnson after saying, “If they ever make me carry a rifle, the first man I want to get in my sights is L.B.J.”

The Supreme Court deemed it was not a “true threat” but rather political hyperbole given the context and therefore protected under the First Amendment.

“England’s politically hyperbolic written poem, left quietly at the Seymour Library circulation desk for the contemplation of any patron or person who happened upon it, falls within the spectrum of permitted First Amendment activities,” Walton Pratt wrote in the decision. “…The evidence in the record does not support that England engaged in disruptive conduct that prevented other patrons from enjoying the library or otherwise endangered them through the inconspicuous dissemination of his poem.”

The judge also found the library violated England’s due process rights under the 14th Amendment, as the library did not allow the plaintiff any kind of hearing before he was banned from the library and was never advised of his right to review the decision to ban him or how to challenge it.

“The resolution of England’s First Amendment and due process claim entitles him to full reinstatement of his library privileges and a permanent injunction enjoining continued enforcement of the ban from the Seymour Library,” Walton Pratt wrote in the decision.