Not enough credit is given to recruits who joined the military from a sense of patriotic duty in the days after the worst attack on America in history, a former Jackson County resident contends.

Sgt. Darel Shelton, a 2000 graduate of Brownstown Central High School, joined the military on Sept. 11, 2001.

That’s the same day terrorists hijacked three planes, crashing two into the World Trade Center towers in New York City and one into the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. A fourth plane crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after passengers onboard overtook the terrorists and foiled their plan to crash into the White House or the Capitol building. A total of 2,977 people were killed in the attacks that day.

“At 18 years old, I had moved into my own apartment and my mother had stayed the evening prior,” Shelton said. “On the morning of Sept. 11, my mother shook me, waking me from my bed.”

She told him the U.S. was under attack and led him to the television where they watched the horror unfold.

“Many join the military for school, employment, experience or to escape a poor home life,” Shelton said. “I, like many others at that time, joined the military because our country was attacked and a strong response needed to be made to deter another attack in the future.”

Shelton started his basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas on March 12, 2002.

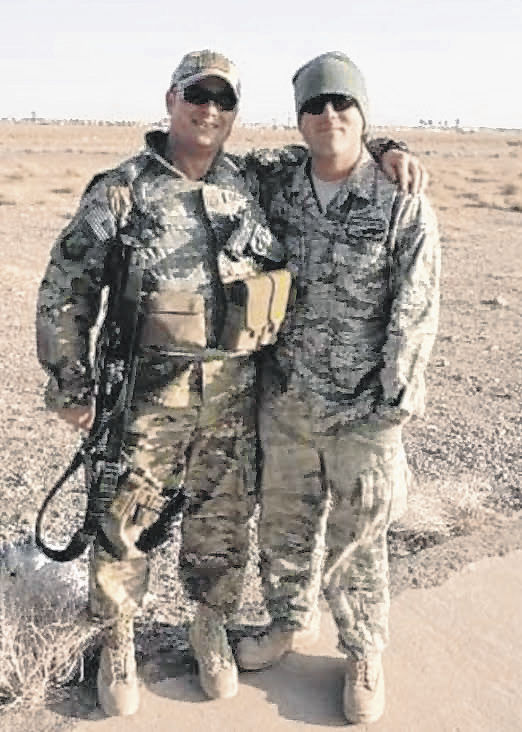

The son of Allen Shelton and Kimberly Hodge, Darel Shelton, 38, now lives in Las Vegas with his wife, Samantha. He recently released a book with stories from the time he spent in Afghanistan.

“A Ticket Back: Coming Home is Never Promised” is available in both Kindle and paperback versions.

“Initially, ‘A Ticket Back’ was meant to be half about Afghanistan and half about getting better,” Darel said. “When some of my family began reading what I was writing, they told me they felt it would be better served as two separate books.”

His family thought he should write one book on Afghanistan and another on post-traumatic stress disorder. Their constructive criticism made sense to Shelton, and he started writing the book around Thanksgiving of 2019.

Sept. 1 was the formal release of the paperback, which is about a typical service member being pulled from his or her family and current military assignment to leave on short notice.

“Only five days to prepare for three months of training and 12 months of Afghanistan,” Shelton said. “It goes on to tell the story of how I was dropped into an Afghan village during the middle of the night and the sights and sounds that accompanied it in the morning.”

Shelton said he was provided with Russian helicopters, a small red metal toolbox and a gaggle of untrained Afghans. Their mission was to build an Afghan Air Force, which had never existed before.

“During my time in Afghanistan, I left my assignment to go to a much more dangerous place for a short period of time,” Shelton said. “The circumstances around that trip were devious, and I’m not sure I should talk much more about it, outside what is already in the book.”

Shelton was a helicopter mechanic by trade, and he worked on helicopters the Air Force calls PAVE Hawks. They are essentially the same thing as the Army’s Black Hawk helicopters.

PAVE stands for precision avionics vectoring equipment. The PAVE Hawk specializes in combat search and rescue operations.

Shelton, who was stationed in Shindand, Afghanistan, said the two most impactful injuries he has from his time of service are PTSD and a low back disc fusion.

“During the ‘wind of 120 days,’ common in eastern Iran and western Afghanistan, the wind starts out in the morning around 25 to 35 miles an hour,” Shelton said. “It keeps getting stronger every hour until the end of the day when the winds are around 75 or 80 miles an hour.”

He said there was a cheaply built aircraft hangar at Shindand Air Base in the western part of Afghanistan, and the doors opened up directly into the wind, so when the winds started picking up, one of the doors was bending back.

“It looked like it was going to snap off, so the commander yelled for us to go shut the door, and my friend, Mike, unpinned it from the ground,” he said. “The wind was blowing harder, and then I saw everybody was running.”

Shelton said he started running, too, and about that time, the 25-by-40-foot door slammed shut harder than a car door.

“When it hit me, it knocked me 20 feet through the air, and I landed flat on my back,” he said. “It dislodged a vertebra from my spine, which essentially free floated until it was bolted down via disc fusion in 2016.”

He has a small limp and will need radio frequency ablations or nerve burnings every six to 12 months for the rest of his life.

Shelton came back home to the United States on March 11, 2012, 364 days after landing in Afghanistan.

Darel wasn’t the first in his family to serve in the military. His father spent 20 years in the U.S. Marine Corps. During Darel’s childhood, the family moved a lot.

His grandma, Mary Jane Turpin, was a single mother of six children. She raised them in an 800-square-foot home on West Vine Street in Brownstown and worked as a butcher.

Between every move his father made, the family would come home to visit all of their relatives in Jackson County. That’s one reason he still calls it home.

“While my parents went to visit family, I would stroll around town looking for old childhood friends, and I never once had any problem finding them,” Shelton said. “My father retired from the Marines when I was in ninth grade, and we moved back to Jackson County.”

“From birth to age 18, I lived several years in the states of North Carolina, Georgia, Indiana, Maryland, New York and three years in Okinawa, Japan,” Shelton said. “I graduated early from Brownstown Central High School Nov. 10, 2000, but our class graduation was June 2001.”

He met his future wife, Samantha, in Las Vegas, back in 2017. She was a pilot, flying tours of the Grand Canyon in Twin Otter planes and landing on a dirt strip at the bottom.

“Without her love and support, it wouldn’t have been possible for me to commit to treatment,” Shelton said. “I most assuredly would not have sought so many different forms of treatment.”

He said it’s because of her that he was able to continue living his life until he found the best combination of medication and therapy.

“We were married April 27, 2019, and I cannot thank her enough for her faithfulness,” he said.

Shelton said he began to enjoy writing in eighth grade upon the conclusion of learning to write his first formal research paper. He loved sharing multiple perspectives of singular events.

“My book is a sad story, but it is a true story. All of it was written by me from my specific memories of the events,” Shelton said. “I did not want to change the names of people and places, but it seemed necessary once I completed the story.”

He hopes readers take away an understanding of the sacrifices made in order to prevent another Sept. 11-style attack.

“I hope it helps people better understand PTSD and veterans,” Shelton said. “Most of all, I hope that it helps people who are looking for a true story about persevering through the darkest of hours and trying every tool in the medicine cabinet before taking their lives by their own hands.”

He said one of the most challenging parts of recovery is simply being able to see a future that you want to live in.

“It just seems unattainable at times, but by making persistent choices to continue treatment and practicing the skills learned, a person can learn to appreciate the positive life around them in the moment instead of living inside the mind’s eye of the past and future,” he said.

Shelton plans on writing more and has a second book in the works.

“A Ticket Back: Coming Home is Never Promised” is now available in both Kindle and paperback versions on Amazon.com.