They flew overhead in clusters, some flocks as large as 50 birds, sandhill cranes flapping wings against an otherwise gray and heavy sky, yakking loudly in their trumpeting calls as they passed.

Heads belonging to human bird counters tipped back, eyes on the sight, marveling at the sheer numbers of the 10-pound.gray birds that kept on coming in flight patterns over Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge east of Seymour on New Year’s Day.

Sometimes, the bird groups were so large they could only be estimated. Always, wings moving in great swoops, they commanded attention, as part of the species migration 450,000 strong.

Steve Wagner gave it his best effort trying to catalogue how many flew by, within an hour of starting in the morning half-light calculating he had seen 2,000 sandhills on the wing already.

Wagner and wife Donna from Milford, Ohio, were among the 21 people participating in the annual Christmas Bird Count at the refuge, sponsored by the Audubon Society all over the country.

“Lots of sandhill cranes,” Wagner said as he glanced up and announced 1,700 he’d seen. Then along came another group and another. “That’s 50 in the last 10 seconds.”

Sandhill cranes were definitely the bird of the moment on this counting day. This marked the 123rd annual Audubon counting period from Dec. 14, 2022, to Jan. 5, 2023.

Twenty-one people is a very good turnout for Muscatatuck, ranger Donna Stanley said. A year ago, when it was a rainy, yucky weather day, there were 10 counters. Many, like the Wagners, have become Muscatatuck regulars. Many also participate in more than one count in Indiana or in their nearby home regions of Kentucky or Ohio.

All across the Western Hemisphere, the humans involved mark how many different species they spot in a single day and keep track of how many of each kind of bird they see, rain or shine, snow or wind. The information collected by tens of thousands of people is transmitted to the Audubon Society and then used to estimate how bird populations are faring, or trending.

Lately, that news has not been especially encouraging. In late 2019, the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology and American Bird Conservancy reacted gloomily to studies indicating there were 2.9 billion fewer adult breeding birds in North America than in 1970. It was suggested habitat change contributed to the decline.

On Sunday, it seemed there were a billion cranes alone near Muscatatuck. On a typical bird count day at the refuge, 70 species are seen. The number was 59 in the rain a year ago. This year, with the temperature starting at about 45 degrees and under gray skies, the total was 63.

The cardinal was named the Indiana state bird in 1933 and the species was seen. So were three kinds of owls, barred, screech and great horn, more visible than usual. Among the rarest sightings were a white-fronted goose and a black capped chickadee. Those kinds of chickadees don’t usually stray south of Indianapolis, Stanley said.

“Cardinals are always popular,” Stanley said. “That’s what it’s about, the variety. It was a good day.”

Early on, Wagner’s group of four saw robins and a few kinds of sparrows, as well. White-throated sparrows, with a loss of 93 million in population from that ominous study, was one species considered most at risk.

The Muscatatuck counters gathered in darkness at the visitor center and rolled out the door in small groups by 7:30 a.m. There was no requirement how long they had to stay in the field, but some made all-day commitments into the other end of darkness.

Long-stayer Dave Carr, who is affiliated with the University of Virginia, was making his 41st trek north, visiting family and the refuge simultaneously. He counted until 6:15 p.m. He said the number of counters was impressive.

“This is the biggest turnout I’ve seen in years,” Carr said.

There are always some first-timers, always veterans and always participants who attend more than one count. There were no obvious super birders compiling meticulous life lists of the total number of different birds they have seen anywhere in the world.

Carr’s life list has 706 birds on it, but that is nowhere close to being in the ballpark of the extreme birders who are well into the thousands, travel hundreds of miles at a moment’s notice to see a single fresh bird or have written books about their adventures.

For the arm-chair birder whose outlook on the flying creatures consists solely of watching out the living room window as they partake of his bird feeder, there are volumes to read on how the most devoted live. One such book is “The Big Year,” the story of some birders competing to see the most different types of birds in a single calendar year. Another is “To See Every Bird On Earth,” about cataloguing more than 8,000 birds.

It is a little vague just how many species of birds there actually are on the planet, but a couple of sources suggest 18,000. However, definitions change, sub-species are added and that is one reason why Wagner said he doesn’t keep a list anymore. Long ago, he was up to 460 species, but he has no idea what his lifetime total would be now.

“I got tired of all the changes,” he said.

Yet he never tires of looking at the vast variety of birds out there.

Holiday counting

Christmas Bird Count merely defines the time period of the bird watch rather than the specific day. Holidays Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day are all encompassed.

Certainly, some other Saturday, or Tuesday, might be more convenient, but the bird counters at Muscatatuck coping with a New Year’s holiday conflict seemed adaptable.

Carr said he was in bed by 9:30 p.m., foregoing midnight champagne, the ball tumbling in Times Square or spending the evening with the ghost of Dick Clark.

Susan Miller of Columbus said she went to bed at 10 minutes past midnight after putting out a “Happy New Year” message on Facebook. The Wagners watched the college football playoffs until 10:30 p.m. Karen Scout, present with husband Jim from Nelson County, Kentucky, said she also sent out a Happy New Year note via Facebook, but at 8:30 p.m.

“There are birds to count,” she added to the salutations.

Miller said she saw a barred owl off U.S. 31 on her way to Seymour for the count.

Erich Baumgardner, a Cincinnati birder at Muscatatuck for the first time, participated in a bird count in Oldenburg the day before.

“We had eagles all over,” Baumgardner said. “Thirty-one juveniles and one adult.”

The Muscatatuck bunch of counters spied seven eagles at the refuge Sunday.

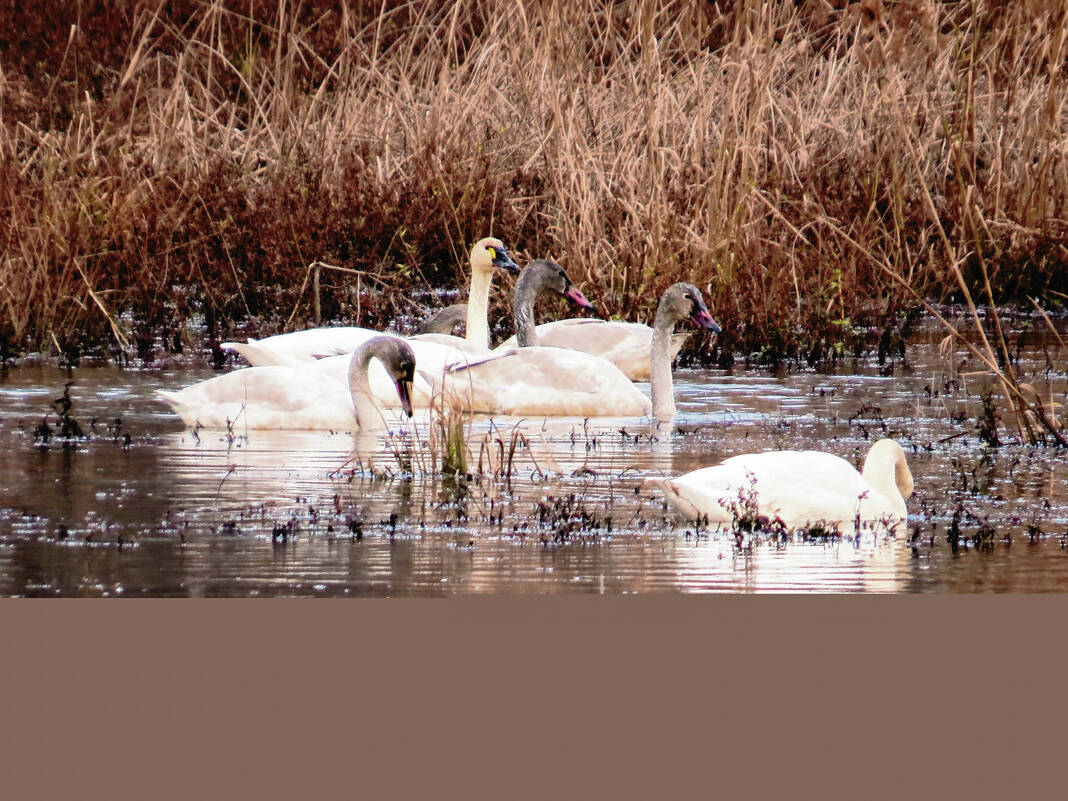

Jessica Helmbold of Indianapolis was counting with mother Ann Babb of Seymour. Helmbold is partial to waterfowl. Stanley, however, warned that it might not be a good day for seeing them. The extreme cold of the week before froze all of the big water in the refuge and despite rising temperatures since the ice had not all melted.

At Richart Lake, there were three of something gliding along through the mists, possibly ducks on the pond, in and out of view. Stanfield Lake was so heavily fogged, nothing could be seen, even if there was anything there.

Helmbold and Babb hopefully checked out the situations but did not see waterfowl through the thick cover.

Contrasting to those ambitious world travelers who write the bird adventuring books, Helmbold said she has one comparative mini-goal.

“I would like to see every waterfowl species documented in North America, 50 or so of them,” Helmbold said.

Sandhill cranes abound

One way this huge gathering of sandhill cranes differs from some other places was the appearance a year or more ago of a single whooping crane in the midst of the mob. The whooping crane is actually an endangered species.

“He does come back every year with his sandhill crane friends,” Stanley said.

When the count reports came in, all top-heavy with sandhill cranes, Stanley made a command decision. Since the cranes were all estimated by overhead flight and each counting group basically saw the same cranes flitting about, suggesting widespread duplication, Stanley decided to report the highest group total of 3,000.

“They flew around all through the refuge,” she said.

No one saw the cranes take off, and no one saw where the cranes landed, and Stanley said there are undoubtedly thousands more in the area.

“They’re playing hard to find this year,” Stanley said.

Except for their time in the sky.

“Where did they spend the night last night?” Helmbold said, announcing what everyone wanted to know.

And where would they spend New Year’s night?