Exploration of Mars is an active endeavor by NASA and private space exploration companies to understand if human life can eventually occupy the planet.

The need for human-based design solutions will become paramount at some point, possibly in our lifetime.

Imagine a human colony has occupied Mars. To mark this significant feat, a monument must be created to commemorate the occasion.

That was the challenge issued by the Museum of Outdoor Arts in Englewood, Colorado, for its third annual national collegiate design competition as part of its award-winning Design and Build program.

Designs should be based on the idea of a permanent installation, and contestants can assume all earthly or unknown Martian material availability in creating design solutions. Students not only had to think outside the box but also out of this world.

Tanner Prewitt, a 2016 Trinity Lutheran High School graduate, partnered with his Ball State University roommate and friend, Malequi Picazo, on entering the competition. Picazo found out about it on an architecture blog.

“Since our thesis projects had actually covered components of this project, we decided to take a chance,” Prewitt said.

Having won first prize for a campus master planning competition with the University of Saint Francis in Fort Wayne in the spring, Prewitt said he felt better about his chances with the MOA competition.

He and Picazo spent several weeks researching Mars, how to design on another planet and niche topics of interest in their fields. Prewitt earned his landscape architecture degree from Ball State in May, while Picazo received an architecture degree.

“Malequi’s undergrad thesis had been about designing colonial homes on Mars. He had most of the necessary research for construction, architecture and materials,” Prewitt said. “My undergrad thesis had been about memorial landscapes, specifically the National Mall. While most of my research had been on historical or political topics, the principles of memorial landscapes still applied to this project.”

They also researched the Martian environment, alien biology and what NASA and SpaceX are doing with regards to colonization.

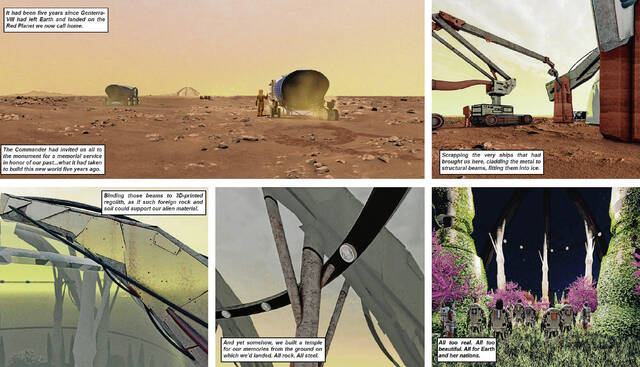

Their seven weeks of intense design work also involved researching and conceptualizing ideas, building a digital model, rendering it with animation software, writing a 3,000-word project narrative and creating a project booklet to submit as a deliverable.

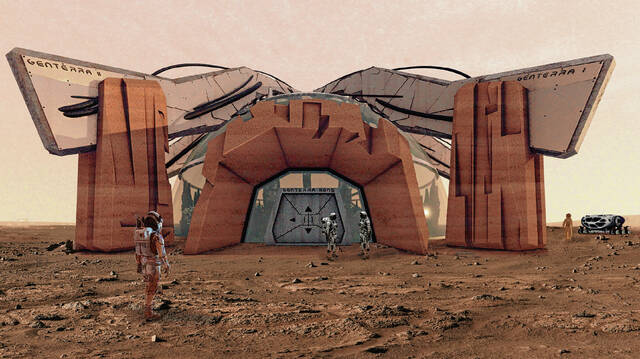

Genterra Mons is Latin for “mountain to the nations of Earth.” Their hypothetical narrative detailed seven spacecraft — the Genterra missions — that brought the necessary resources and multinational team to colonize Mars.

Firstly, the memorial is a technological marvel built by droid systems and three-dimensional printers, Prewitt said.

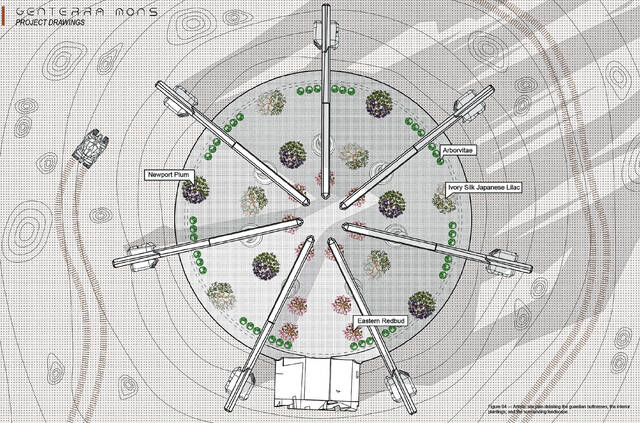

Secondly, it’s a biological phenomenon that uses artificial processes to make Martian soil arable. Thirdly, it is a sacred memorial space.

Brutalist-style guardians made of bedrock material and metal buttress the ice dome and protect the earthly plants inside. These Martian and earthly elements along with the experiences of each colonist become a living memorial element, less so than a museum or monument to a historic event or deceased entity, Prewitt said.

“I knew we would have to stand out from other submissions,” he said. “Previous winners had hailed from Ivy League programs or top-ranking state schools.”

On Oct. 19, Prewitt and Picazo found out they were finalists. They then had to prepare a 15-minute presentation for the competition jury, which was done virtually Oct. 26.

Two days later, they were notified they won.

“I think I stayed in a state of shock that whole weekend,” Prewitt said. “I just couldn’t believe we had won our first national design competition. If anything, I think it speaks to Malequi’s and my hard work and talent and also to the incredible design program at Ball State.”

They received $5,000 and will have their winning entry archived and featured on the competition website.

The MOA said students flexed their creative muscles to design their conceptual projects for the red planet.

“While the competition is primarily architectural in nature, it provides an opportunity for students to think about integrating art and landscape into architecture,” MOA President Cynthia Madden Leitner said in a news release. “This aligns with the Museum of Outdoor Arts’ history of creating environments that are a synthesis of art, architecture and landscape.”

The goal of the competition is to cultivate potential from emerging artists, architecture and design students and other creatives and allow students the space to conceptualize inventive ideas within a set of boundaries, according to the news release.

The competition garners an online repository of art, architecture and design concepts. The goal is to take the competition to an international audience and collaborate with creatives across the globe in the future. It also is the hope to be able to realize and build student design prototypes in the future.

The competition currently is only open to students attending college in the United States but will begin accepting international entries in the coming years once the program is further established nationally.

A call for the next competition challenge will go out this winter. It will be open to individuals, teams and university faculty who wish to take the competition on as a class project.

Prewitt said he has benefited from participating in the competition.

Professionally, he was interviewed by the marketing and public relations departments where he works, Luckett and Farley in Louisville, Kentucky, to discuss his work.

“It has created some buzz in the office, and firm leadership is looking to pursue additional design competitions as a result,” he said. “This project will be a great segue into those experiences.”

Personally, he said he’s excited to search for other design competitions to hopefully build his résumé with other awards.

“These are great ways for designers to design without restrictions like budgets, bureaucratic red tape and the other details associated with built projects,” Prewitt said.

When he started at Ball State, Prewitt said he thought he wanted to become a traditional architect. Once he was in classes and studios that exposed him to various design principles and fields of study, he found himself thinking and designing more like a landscape architect.

When it came time to declare his official major, he chose the landscape architecture program, which would take him five years to earn a professional degree.

After the cumulative first-year program, Prewitt took another eight semesters of studios, general classes and electives.

“Studios taught design thinking and creativity. I had general classes for technical skills, software use, horticulture and professional development, and electives were specialized courses functioning more like a robust studio,” he said. “These all mimicked design firm environments and set the building blocks for necessary skills in the profession.”

At Ball State, he was enrolled in the R. Wayne Estopinal College of Architecture and Planning and the Honors College.

The latter is a traditional liberal arts school with curriculum in the humanities, philosophy, sociology and politics. Prewitt was part of the Student Honors Council, the college’s student government, and served one term as president in 2020.

In CAP, he served on the editorial board of the college’s design journal, The Glue Publication, and two terms as president of the Student Chapter of the ASLA in 2019 and 2020. The American Society of Landscape Architects is a nationally recognized landscape architecture advocacy group with 50 state chapters and student chapters in schools with accredited landscape architecture programs.

Now, Prewitt is a landscape designer at Luckett and Farley, a multidisciplinary design firm.

He works on parks projects, master plans, graphic design, publishing and research and development. The projects have been as small as a municipal park to as large as replanning a city.

“Like any professional degree, I’ll have to take licensure exams so I can one day be Tanner Prewitt PLA (Professional Landscape Architect),” he said. “Until then, I’m learning all I can so I’m ready for those exams in the next few years.”

Prewitt said he chose landscape architecture because it felt like the only field that still allowed him to be an artist.

While he would consider himself more of a designer than an artist now, he said that creative expression is nearest and dearest to him.

“Students or young people passionate about any of the things mentioned above should seriously consider researching landscape architecture and its related fields. They might find it’s just the right thing for them,” he said. “I never imagined I would be designing on Mars, but that’s the beauty of the design world. It can be out of this world.”